New African Urban Studies on Springfield, MA

- Social Movement Organizing Against the New Jim Crow: Two Essays on Charles Wilhite

- A Story of the Incarceration of a Young Afro-Springfield Man in “Camp Hamp”

- Reverend Dr. William N. DeBerry — an entry submitted to Wikipedia

- Primus Parsons Mason — an entry submitted to Wikipedia

- Engaging with the Putnam Vocational Technical Academy Boys Basketball Team

- Dr. Ruth B. Loving — an entry submitted to Wikipedia

- A Personal Essay on Springfield’s Arise for Social Justice

- A Personal Essay on the Case of Ayyub Abdul-Alim

__________________________________________________

Brittney M.

Wrongful Convictions

On September 18, 2009 Charles Wilhite of Springfield, Massachusetts pled not guilty to the murder of Alberto Rodriguez but was found guilty of the murder and convicted of first degree murder. Wilhite was sentenced to life in prison without the chance of parole at the age of 24. Wilhite was charged without any physical evidence linking him to the murder of Alberto Rodriguez. The shooter was originally described by witnesses as a fair skin Latino male with facial hair, which was a description that did not match that of Charles Wilhite. Despite presenting over 50 exhibits for the jury to examine the jury reached their verdict in merely three hours. However, while the trial was taking place one of the key witnesses recanted her statement and after the trial another witness recanted their statement as well, admitting that he had lied when identifying Wilhite as the shooter in the photo line-up. The witness came forward describing how police intimidation made them falsely identify Wilhite as the shooter. On May 15th 2012, Judge Constance M. Sweeney granted Charles Wilhite a new trial. The second trial began on January 7th 2013 and Charles Wilhite was found not guilty of the murder of Alberto Rodriguez (justiceforcharles.org).

On September 18, 2009 Charles Wilhite of Springfield, Massachusetts pled not guilty to the murder of Alberto Rodriguez but was found guilty of the murder and convicted of first degree murder. Wilhite was sentenced to life in prison without the chance of parole at the age of 24. Wilhite was charged without any physical evidence linking him to the murder of Alberto Rodriguez. The shooter was originally described by witnesses as a fair skin Latino male with facial hair, which was a description that did not match that of Charles Wilhite. Despite presenting over 50 exhibits for the jury to examine the jury reached their verdict in merely three hours. However, while the trial was taking place one of the key witnesses recanted her statement and after the trial another witness recanted their statement as well, admitting that he had lied when identifying Wilhite as the shooter in the photo line-up. The witness came forward describing how police intimidation made them falsely identify Wilhite as the shooter. On May 15th 2012, Judge Constance M. Sweeney granted Charles Wilhite a new trial. The second trial began on January 7th 2013 and Charles Wilhite was found not guilty of the murder of Alberto Rodriguez (justiceforcharles.org).

Vira Cage a community activist, with the help of the Sprigfield community joined to create the organization Justice for Charles. The organization held events to get attention from the government and the local community about Wilhite and his wrongful conviction. Cage who is also Wilhite’s aunt was already involved in community organizing and was able to gain more support. The organization held events such as a panel discussion in September 2012 on “Resisting the New Jim Crow in the Pioneer Valley and the Campaign to Free Charles Wilhite of Springfield”. In June 2012 the organization held a Vigil to commemorate Wilhite’s 1,000th day in custody. In March of the same year they held several events including: a rally for Peace, Justice, Dignity, and Respect: For the Unity in the Community; Here and Now, a community dialogue on race and justice; and the Justice for Charles Campaign kick-off and cook-out. The community was persistent on bringing attention to inequalities in the justice system and letting Wilhite know that he had the support of the community behind him. With the help of the organization Wilhite’s family was able to raise enough money to hire a reputable attorney, and not rely on a public defender (justiceforcharles.org).

Justice For Charles was strongly influenced by another community organization called Justice for Jason, which is an organization that helped a student who attended UMass Amherst in 2008. In February 2008, Jason Vassell was a victim of a hate crime committed by two white men. Vassell was attacked in his dorm room by the two men who were not Umass students. The men entered the building shouting racial slurs entered Vassell’s residential building with the intention to fight. Vassell responded with self-defense and when the police arrived they questioned both parties. Vassell was later arrested and charged with “two counts of aggravated assault and battery with a dangerous weapon and two counts of armed assault with intent to murder”. The two men who were part of the East Milton Mafia, a white supremacist group, were not charged. With the help of the community, Justice for Jason was established to fight for racial justice against the unjust criminal system. Vassell was later released on bail and was cleared of charges. Similar to Justice for Charles they held many events to bring attention to the cause. For example, a Justice for Jason rally Northampton, MA, UMass Amherst held a faculty press conference, and in Feburary 2010, they held a vigil for Jason (justiceforjason.org). The attention and success that Justice for Jason was used a reference by Justice for Charles applying some of the same techniques used in Vassell’s case.

Throughout 2013 the media have begun to bring more attention to stories of wrongful convictions, such as that of Charles Wilhite. Derrick Deacon a resident from Brooklyn, NY was convicted in 1989 of the murder of Anthony Wynn during a robbery. A key witness in the trial recanted her statement and also cites being intimidated. Before Deacon was granted a second trial he had already served 24 years for a murder he did not commit and wasn’t released until 2013 (Yaniv). In another case, Michael Cosme, Devon Ayers, and Carlos Perez were convicted in 1995 for killing a FedEx executive. After serving 17 years in prison the three men were released in January 2013. Kash D. Register was convicted in 1979 of murdering Jack Sasson and after serving 34 years in prison he was released after he was found not guilty (Powell). In this case, the prosecution and police department hid valuable evidence that may have otherwise proven Register’s innocence.

Compared to some of the other cases Charles Wilhite was lucky to be granted a retrial after 3 years, unlike so many who have served over a decade or more before they were granted a second trial. One factor that ties all these types of cases together is that they disproportionately happened to young men of color. All the men mentioned above were young black men at the time of their convictions. Law enforcers have a duty to protect society and bring to justice those that impede on its safety. In order for them to do their job effectively they have to build a level of trust among the community they are responsible to protect. However, these cases break down that trust making it more difficult for law enforcement and community members to work together.

In September 2013, 474 New Yorkers were interviewed by the Vera Institute of Justice. An organization that on their site states they are “making justice systems fairer and more effective through research and innovation” they work for social justice and did some research to find out how communities in areas predominantly of color felt about police officers. All of those interviewed had been stopped at least once by police and lived in communities that were predominantly of color. Only 40% of those interviewed felt as though they would be comfortable calling the police and only 25% of them would report a crime being committed even if they were the victim of the crime. Only 45% of those interviewed claimed the officer who stopped them threatened them, 46% said they experienced physical force, and 1 out of 4 claims that at the time of the stop the officer displayed his or her weapon. 88% of the people interviewed feel as though the residence in their community do not trust the police. This survey demonstrates a level of mistrust between communities of color and the police in New York and how it may contribute to wrongful convictions. Organizations like The Vera Institute, Justice for Jason, and Justice for Charles have been bringing attention to inequalities in the justice system and bringing an end to this unsettling trend throughout the country.

Works Cited

Fratello, Jennifer. vera.org . N.p., 09 2013. Web. 20 Dec 2013.

<http://www.vera.org/project/new-york-city-close-to-home-initiative-data-capacity-study>.

Justiceforcharles.org

Justiceforjason.org

“Michael Cosme, Devon Ayers, And Carlos Perez Freed After 17 Years In Prison For Murder

They Didn’t Commit .” Huff Post New York. Huffington Post , 24 Jan 2013. Web. 20 Dec 2013. <http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2013/01/24/wrongful-murder-conviction-michael-cosme-devon-ayers-and-carlos-perez-freed-prison_n_2543897.html>.

Powell , Amy. “Wrongly convicted man released after 34 years.” abclocal.go.com. ABC, 08 Nov

2013. Web. 20 Dec 2013. <http://abclocal.go.com/kabc/story?id=9319203>.

Yaniv, Oren. “Brooklyn jury acquits man of murder 24 years after he was jailed for the crime.”

nydailynews.com. New York Daily News, 18 Nov 2013. Web. 20 Dec 2013. <http://www.nydailynews.com/new-york/nyc-crime/brooklyn-jury-acquits-man-murder-24-years-jail-article-1.1521151>.

************************

Emily S.

THE CASE OF CHARLES WILHITE – Draft case summary for Consideration as a Wiki Entry (Fall 2013)

Springfield, MA resident Charles Wilhite (born _______) was convicted and subsequently acquitted of the October 14, 2008 murder of Alberto Rodriguez. His sentence was overturned on January 17, 2013 following the emergence of evidence that Springfield police had behaved unlawfully in their investigation. Wilhite’s wrongful conviction compelled the mobilization of activist group Justice for Charles, which continues under different names to campaign against abuses on the part the Springfield Police Department.

At roughly 9 p.m. on the evening of October 14, 2008, Alberto Rodriguez pulled his white Toyota up to the Pine Street Market located in the Six Corners district of Springfield, MA. Rodriguez had been involved in an altercation with the market’s owner Angel Hernandez a day prior and had been banned from the market. A group of individuals began shouting at Rodriguez upon his arrival at the market. Moments thereafter a man approached Rodriguez’s vehicle and fired multiple bullets. Despite being struck Rodriguez attempted to escape; he managed to drive several blocks to Ashley Street before colliding with a parked sedan, pushing it into a pick-up truck parked outside 21 Ashley Street. The incident was initially reported to police as a car accident. Springfield Police Officer William Kelly testified that he arrived on the scene to find Rodriguez slumped over in the driver’s seat, breathing in a shallow and unresponsive manner. Both the driver’s and front passenger doors were open, and multiple bullet holes were observed on both the interior and exterior of the vehicle. Rodriguez, 28, was pronounced dead in the hours thereafter at Baystate Medical Center.

On September 17 2009, Charles Wilhite was arrested and interrogated on charges of murder in the first degree. Also being charged with the murder was Wilhite’s co-defendant Angel Hernandez, owner of the Pine Street Market.

On November 15, 2010 the case went before a trial judge. The trial included testimony from 19 witnesses and 55 exhibits of evidence. Significant testimonies and evidentiary material most pertinent to the conviction of Charles Wilhite are delineated below.

Madelyn Dones, girlfriend of victim Alberto Rodriguez, testified that she had driven from the area of Cedar and Ashley Streets towards the Pine Street Market on October 13 2008, the day immediately prior to her boyfriend’s murder. Upon arrival at the Pine Street Market, she witnessed victim Alberto Rodriguez engaged in a physical altercation with two Latino youth. She yelled for Rodriguez to get in her car. As Rodriguez entered her car, the two youth pursued and continued to strike him.

Roberta Sosa gave testimony indicating his presence at the Pine Street Market on the evening that Rodriguez was shot and killed. At this time he witnessed store owner Angel Hernandez with a gun. He reported that he had not seen anyone else in the area of the market and had never seen Charles Wilhite prior to appearing in court to give testimony.

Patryce Archie, witness for the prosecution, testified having been in the Pine Street Market at the time of Rodriguez’s murder. She denied seeing Hernandez hand off a gun to any other individual. She recounted witnessing Hernandez go down an aisle of his store, retrieve a gun, and then exit the store. In addition to her and Hernandez, she indicated the presence of two other individuals in the store at the time of the shooting – a black man wearing chef pants, and a Puerto Rican woman who she estimated to be about her height (5’7”). She made no mention of the presence of any other individuals in the store. She did, however, testify that she observed two men standing by a fence near the house next to the market after the shooting took place. One of these two men, according to Archie, wore a grey hoodie. Archie indicates having been brought to the police station on November 6, 2008, 23 days after the murder. During this visit she was shown a photo array of black males that included Wilhite. She selected the photo of Wilhite from the array on the basis that his lips appeared similar to those of an individual she had observed outside the market on the night of the shooting. She indicated that she had gotten only a “one-second glance” at the man outside the store on the night of the shooting, and concluded that, in her estimation, Wilhite “might” have been outside the store at that time.

Nathan Perez, witness for the prosecution, gave testimony under grant of immunity. He agreed to act as a witness for the prosecution in March of 2010, 6 months after the arrest of the co-defendants. At this time he was facing new charges for receiving a stolen motor vehicle and resisting arrest; he was additionally facing accusations charging that he had violated the terms of his probation. He testified that, despite having “blown off” police on previous occasions, he had chosen to speak with them once facing his own legal issues. Perez is a light-skinned Latino male. He testified that he was in the Pine Street Market at the time of the shooting. After being shown an array of single photos, he selected Patryce Archie and Giselle Albello as having also been present in the market at the time of the shooting. During his first visit with the police he was shown a photo array of black males which included Charles Wilhite; he did not at this time identify Wilhite as the shooter. His later testimony, however, given in court, did place Wilhite at the scene of the crime. Later testimony offered by Perez identified Wilhite as the shooter. He testified that he had disposed of shell casings (believed to be those involved in the shooting of Alberto Rodriguez) in the apartment of Anthony Martinez, whom he knew as “Tonka,” on the night of the murder. He additionally testified that he witnessed the shooter take the gun from Hernandez, leave the market, cross Pine Street, approach the open front driver’s side window of Rodriguez’s car, place the gun almost inside the vehicle and fire three bullets. This testimony was at odds with physical evidence presented in the case. Medical examiner Dr. Mednick and Sergeant John Crane, the prosecution’s expert witness on ballistics, both asserted their belief that the bullet which had killed Rodriguez likely struck an object prior to entering the victim’s body; the testimony given by these individuals, which was issued on the basis of physical evidence taken from the crime scene, suggested the unlikelihood that the shooter fired directly upon the victim through an open car door window, as indicated by Nathan Perez.

Giselle Albelo is a Latino woman who is approximately 5’2”. Her initial November 5, 2008 statement to the police asserted that she had been in the Pine Street Market at the time of the shooting. This statement further indicated that she had witnessed a black male approximately 18 years of age shoot the victim, who stood outside his car on the pavement outside the market, in the back; she continued that she had then seen the victim get in his car and drive away. She selected a photo of Charles Wilhite as being the shooter. Wilhite, who is a black male, was 25 years old at the time of shooting. On the 3rd of November, 2009, Albelo signed an affidavit which contradicted her original statement to the police. In this affidavit Albelo asserted that she had felt “fear and extreme pressure from the police to provide certain details” at the time of her initial statement, and that as a result she had not been “completely accurate or truthful about everything in the statement.” In this affidavit Albelo stated that any information placing her inside or outside the Pine Street Market at the time of the shooting is false, that she was inside her apartment at the time of the shooting and could therefore not possibly make any identification of the shooter, that she had based her original statement to police on a conversation she had had with a resident of her apartment building, and that she was not a witness to the shooting. Albelo further indicated that she had been in the Pine Street Market on the evening in question, but had left the market 45 minutes to an hour prior to the shooting taking place.

The defense called upon three civilian witnesses who reported being in the vicinity of the market at the time of the shooting. Maria Torres testified that she was in a parked car outside the Summit Package Store on Central Street at the time of the shooting. Torres reported having heard approximately four shots fired and moments later witnessing a light-skinned Hispanic male running from Pine Street turn onto Central and continue running down Central in the direction of Rifle Street. She indicates that she observed this running individual holding a shiny object which resembled a gun in his right hand. Torres spoke with police and was shown a photo array of black males but did not select any of the individuals pictured. She was then presented with a photo array of Hispanic males, one of whom she selected as the shooter on the basis that his skin tone resembled the man she had observed running down Central Street. Alma Reyes was also in the car with Torres, and gave a testimony which matched that of Torres. Elizabeth Lopez testified that she was living in a first floor apartment at 263 Central Street at the time of the shooting. Her testimony indicates that she heard roughly 3 shots fired and soon thereafter observed a Hispanic man holding an object resembling a gun running down Central Street, past her apartment.

Medical records substantiating an injury in the left ankle and leg on the part of Charles Wilhite at the time of the shooting were presented by the defense. Three witnesses testified having observed Wilhite struggling to walk at the time of the shooting.

Physical evidence presented suggested that the Springfield Police Department had discovered fingerprints on the vehicle driven by the victim at the time of the shooting. None of these prints matched those of Wilhite. Further physical evidence pertained to gunshot residue found on the palms and backs of hands of Tyrell Campbell, an individual alleged to have been present on the scene of the crime at the time of the shooting. This residue suggested that Campbell had fired a gun shortly before being questioned by the police. Springfield police nonetheless refrained from any further contact with Campbell.

This first trial in the case of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts v. Charles Wilhite began on November 19th 2010 and concluded 14 days later on December 3rd, 2010. After deliberating for just an hour, a jury produced a sentence rendering Charles Wilhite guilty of murder in the first degree.

Three days later on December 6, 2010, a member of the deliberating jury informed the court that he had been assaulted on the evening of December 3rd. The juror in question, a Hispanic male, had been assaulted by two caucasian males at the Pride Gas Station on Plainfield Street in Springfield; in addition to physically beating this juror, the assaulting males had yelled racial epithets and assorted threats at him. The juror reported his inability to keep the incident out of his mind while participating in the deliberation; after interviewing this juror, the trial judge removed him from the deliberating panel and replaced him with an alternate. The judge then ordered the new jury to once again undertake their deliberations. This constituted jury deliberated for just three hours before once again returning a guilty verdict, convicting Wilhite of murder in the first degree.

On December 9th, 2010, the defense issued a Motion After Discharge of Jury requesting that guilty verdict be replaced with a verdict of not guilty, or alternatively, that a new trial be ordered. This motion charged that the verdict went against the weight of the evidence, and that the integrity of the evidence was suspect.

In April of 2011 the Commonwealth issued a memorandum in opposition to the defendant’s motion seeking a finding of not guilty or a new trial. The prosecution introduces this memorandum with the assertion that significant evidence substantiates the jury’s finding that the defendant shot and killed Rodriguez, that this verdict was not in fact against the weight of the evidence, and that the verdict should be left undisturbed. This memorandum briefly reiterates the evidence presented at trial. It recounts Hernandez driving his mother’s white car down Florence Street towards the Pine Street Market just before 9 p.m. on October 14, 2008. It cites the ongoing and well-known feud that existed between Rodriguez and store owner Hernandez. This memorandum recalls the testimony of Roberto Sosa, who testified having been in the Pine Street market on the night of the shooting and having observed Hernandez grow very angry and agitated, alleging that the victim had driven by and flashed a gun at him. Sosa recalls Hernandez showing him a handgun that he was wearing on his hip, repeatedly pointing down the street towards Rodriguez’s mother’s house, and “talking recklessly.” The memorandum continues that, upon witnessing the victim pull up to the market in a white car, Hernandez ran outside his shop and passed a firearm off to Charles Wilhite, who then shot the victim. The prosecution recounts the testimony of Madelyn Dones, asserting that this testimony establishes motive on the part of Wilhite’s codefendant Hernandez, a motive which was corroborated by the testimony of Sosa. This memorandum cites Patryce Archie, Giselle Albelo and Nathan Perez as the main civilian witnesses in the Commonwealth’s case, arguing that each of these individuals was present at the scene of the crime and subsequently provided identification evidence which either placed Wilhite at the scene of the crime or identified Wilhite as the shooter. The prosecution denied that a grant of immunity had in any way impacted the testimony offered by Nathan Perez as the jury had been fully and repeatedly informed of this fact. The prosecution then expounds upon the testimony of Nathan Perez and details the manner in which other witnesses had supposedly corroborated his testimony. The memorandum concludes with the suggestion that the court deny the defendant’s Motion After Discharge of Jury.

On August 17, 2011, roughly 8 months after the conviction of Charles Wilhite, Nathan Perez issued a statement retracting his testimony. In this statement he admitted to lying and giving false testimony for personal benefit. He never spoke to police until he was incarcerated for violating the terms of his probation in February of 2010. When the police first visited Perez in prison, he refused to give them a statement and they left angry. When the police visited for a second time, they informed Perez that his cooperation would earn him the removal of possession of a stolen motor vehicle from his record, and that he would have neither a larceny nor adult record. Police also informed Perez that, should he not cooperate, he would be charged with “accessory after” in the shooting of Rodriguez for having picked up the bullet shells. Perez then complied with the police’s request for a statement. All this he describes in his testimony retraction statement. He further describes that the two detectives who approached him during his incarceration showed him a single picture of Charles Wilhite, separate from all other photos which had been presented as an array. Detective Pioggi asked Perez if he recognized Wilhite, and Perez replied that he did not. Pioggi replied “Yes you do,” to which Perez replied once more “No I do not.” Pioggi then told Perez that if he did not know Wilhite, he would be charged with accessory after the fact. Pioggi then wrote “shooter” under the photo of Wilhite and instructed Perez to initial it. In his testimony retraction statement, Perez asserts that Charles Wilhite was not at the crime scene as he had previously alleged in court, and that he never saw Wilhite at any time on the day of the shooting. Perez did not know Wilhite. He admits in this statement that he did not actually see the Hispanic lady about whom he testified in court. The only customer he observed in the market on the evening of the crime was a black lady who left before the shooting took place.

[Sources go here]

************************

Leah D.

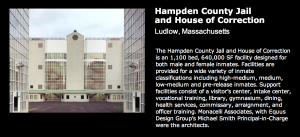

Hampden County Correctional Facility: A Personal Narrative

The prison industrial complex is a multi-billion dollar industry that banks on the ‘criminality’ of young people of color. Taking the brunt of this corrupt system are young men (and women) of color in low-income urban areas.

The affect of mass incarceration on the city of Springfield is devastating. The cities public school to prison pipeline is a reality that robs young people of opportunity and rips families apart. Having been relatively well versed in critical race theory and issues of mass incarceration from my time in STPEC, I was confident in my understanding. It turns out that theory and practice have unbridged gaps, as many of us STPEC majors are shocked to find out. For example, having closely read The Condemnation of Blackness, and The New Jim Crow did not prepare me to understand the real life struggles of those who suffer from this phenomenon. During my time as an intern with Arise for Social Justice, I had the opportunity to organize around the issue and become personally invested in the cause. When I returned to Umass in the fall for my senior year I was determined to continue doing activism around the cause. Little did I know, my commitment to this injustice would not end at community activism or a theory stuffed article on the evolution of ‘black criminality.’

In the early hours of Friday, November 22, my friend was arrested at my apartment by Amherst police and taken into custody. He will be locked up at Hampden County Correctional Facility until January, 3, 2014.

Jacob is a 24-year-old Springfield native that I met through Arise. From the very first day we met, I was inspired by his drive and passion for hard work. He was not entirely on board with the Arise mission, but he took the job with an open mind and willingness to learn. I convinced him that there was no better place to be paying off community service hours. By the end of the summer and our work at Arise, we had grown undeniably fond of each other. When I returned to Amherst for the start of my senior year, I was in a committed relationship.

Jacob was arrested for driving with a suspended license in the spring of 2012. The original court fee was $250. He never paid the two hundred and fifty dollars. The court fee is now at $1,200. Jacob had known for a couple of weeks that the likelihood of a warrant was probable, as he had called to negotiate. He told them he had $400, and they said “too bad,” you can expect a warrant in a few days. They said it had been too long, and that that they would not take anything now but the full amount.

Feeling frustrated and defeated, he was preparing to turn himself in after the holidays if he could not come up with the total balance. He wanted to spend Christmas with his son whom he has dual custody over with his ex-girlfriend. For him, it did not make sense to hustle through the holiday season to pay the court instead of providing the kind of Christmas his son deserves. I was preparing to say goodbye in the near future, as I had exhausted all of my financial options. Unfortunately, things happened quite differently than either of us were prepared for.

I was the one who called the police on Jacob. We were in a late-night argument when he fell to the floor unconscious mid-sentence. With nothing but a couple of joints in our systems, I immediately thought something was very wrong. I did everything from poor water on him to slap him, finally yelling, “Please give me a reason not to call 911!”After a few minutes with zero response, I made the decision to call. In the five minutes it took the paramedics (and police) to arrive I tried to think of ways that I could refrain from giving them his full name; all the while frantically pondering the possible reasons for his collapse.

He awoke several minutes after the responders got there, and immediately told them his full name. I was staring at him with intensity, desperately trying to understand where his mind was. He was clearly very out of it. What seemed like seconds later there were four white, male officers on top of him. He was not trying to resist, nor was he violent. I told them to stop and that he was fine, and they said, “You should reconsider your choice of partner!” I was completely awestruck. What did that mean? I am a white woman from Amherst, and he is a black man from Springfield. That is all they know. He is not a criminal. He owes the court money that he cannot pay. Before I had the chance to get very angry with them he was forcefully dragged out of my apartment by an unnecessary volume of law enforcement. As the last officer was leaving my apartment he said to me “You are a bright, intelligent woman that has the world at her feet. There is no sense in being around that guy.” I shut the door. They never cared to investigate why he passed out in the first place…

Upon news that he would be transferred to “Ludlow” by 3 o’clock that day, I decided to do some research. What was this “Ludlow” all about? The general discourse around jails in western, Ma from my local network is that Hampshire County Jail is better described as “Camp Hamp,” while Ludlow is more aligned with a state penitentiary. Hampden County Correctional Facility is in fact just a county jail, contrary to the tofu curtains perception that it is an entirely different category than “Camp Hamp.” Unfortunately, it appears that this distinction may have a truthful basis.

The opening mission statement of the facilities home page is as follows. “The Hampden County Correctional Center has a deserved national reputation for its innovation in facility and community programs. The Hampden County Correctional Center is considered a model of safe, secure, orderly, lawful, humane, and productive corrections, where inmates are challenged to pick up the tools and directions to build a law-abiding life in an atmosphere free from violence.”

There is a goofy picture of a white man looking large and in charge, equipped with an American flag as a symbol of his patriotism. His name, Michael J Ashe Jr., head Sherriff of the Hampden County Correctional Facility. I was interested in what his story had to offer. I deliberately look for ways to challenge my rigid conceptions of right and wrong, good and bad. How can a man that devotes his life to lock-up enforcement possibly be a decent human being? How can a man who says his correctional supervision is “Strength reinforced with decency; firmness dignified with fairness”, have any understanding of institutional racism and oppression? To me, he is just an agent and beneficiary of the exploitive cycle of mass incarceration. I immediately demonized him (as I tend to do), so I was looking for anything that may spark a counterpoint to my pre-conceived notions.

To my dismay, his biography was most certainly in line with my uninformed judgment. He went to a conservative undergraduate college and has an extremely narrow and nationalistic set of core values. The ‘criminality’ of the inmates is framed as an entirely individual problem stemming from poor individual choices. There is zero mention of ways in which preventative service programs, advocacy, or structural change could help alleviate these peoples ‘criminality’. I have been conditioned to understand the perspective of police enforcement to be rigid, ignorant, and uninformed. To see issue of criminal behavior as independent from systems of race, class and gender inequality and oppression is lacking, to put it lightly.

Michael J Ashe believes this. “The offender who desires to build a law abiding life should be challenged with the opportunity to pick up the tools and directions to do so, and that this should take place in a safe, secure, orderly, demanding, lawful and humane environment, where staff and inmates are free from violence.” When I finally spoke with Jacob at our first visit, his experience thus far was quite the contrary. Not only were these “tools” hidden and the “safety” a gamble, but also he could not pinpoint anything “humane” that had happened yet.

My first visit to the jail was 72 hours following his arrival. It was all of disturbing, informative, and thought provoking. The visiting room was packed with people when I arrived. I made my way to the counter to ask the officers how the visiting works. They were extremely rude to me and said in a monotone voice “Put your i.d. in the basket, fill this out and wait.” As I stood squished between a baby carriage and a locker that I could not figure out how to work, I questioned my presence. Unsure if my perception was a result of my acute anxiety, I could not help but feel like I was a fish out of water.

I was one of two white people in a room filled with at least sixty people and most people were in groups or with their families. I felt like everyone around me was used to the environment, and could sense my “rookie” status. I use this word in part because I was asked by an older man in line with me if I was a ” rookie.” It was exactly what I needed, as my nerves were replaced with laughter for a short time. I guess when visiting a loved in prison become a normative part of life; loved ones find ways to make light of the high-stress situation.

When I finally made my way into the visiting room the only thing I could hear was people speaking Spanish and one woman banging her phone against the glass window. I felt like I was in a movie. Every stereotype I had about prison was boldly painted all around me. Orange jump suits, check. Glass barriers and a phone, check. Overwhelming racial dis-proportion, check. None of my ideas were being challenged.

Very clearly trying to appear strong for me, Jacob was straight-faced and calm. He said everything was fine and kept the focus on me. As I studied his body language and facial expression, for a moment I felt like I was looking at stranger. The strong, prideful manner in which he carries himself was replaced by humiliation and vulnerability. His shoulders were hunched, his arms real close to his body and a look in his eyes that made me cry. He did not hold his head as high. It looked like the dark green fabric that hung over his underfed frame was pinching him with little needles or injecting him with poison. His hands and his neck looked so uncomfortable as they made their way out from the threaded constraints of the jump suit.

I tried to explain to him why I had to call the police, and how hard I tried to keep his full name out of their reach. He kept telling me it was not my fault and that he was going to end up there one way or another. In a way I know that, but I cannot help but feel some sort of responsibility for the situation. Jacob would at least be with those he loves for the holidays. The bizarre series of events that landed him in lock up made it more difficult to accept.

It has now been almost three weeks since the arrest, and I have made six visits. Each time is a different experience. One officer in particular has taken particular interest in me. We have developed somewhat of a friendship actually. He is the on-duty nighttime correctional officer, and since all of my visits are after 9pm and the place is usually pretty empty, it is a much more accommodating scene than the heavy traffic 2:30 visits. I was in tears the first time he met me. I was so shocked he took the time to ask me what I’m doing there, I ended up opening up my entire life story. If any one or anything has challenged my demonization of the criminal justice system at large, it is this man. For that, I cannot thank him enough.

Something I have been noticing more and more during my visits is the attitude I get from white-male officers. I am not sure if I am being paranoid or over thinking, but I really feel like I am looked at differently. I had one officer ask me, have you ever done this before? I said, “Yes, a few times, why?” He said, “You do not look like the kind of girl that comes in hear often.” I shrugged and walked passed him. Why do they react to me like this? What kind of girl comes in here? How can someone in your position be capable of such ignorant generalizations? This really makes me angry. Now he is the only officer that has said this to me. That said, I feel like the expression on the face of every officer I see from the parking lot to the visiting booth is asking me the exact same questions. Is it my whiteness? There are some white people there. Is it my blonde hair? My backpack? I do not wear expensive clothes or flashy Umass gear. I continue to be bothered by this overwhelming attitude towards my presence in a jail. It is making me angrier at the system than I was before. I want to be able to visit my boyfriend with respect and dignity. Without being judged for my situation or my seemingly unwelcome presence. My privilege as an upper middle class white woman from Amherst is magnified and lit on fire when I am inside those walls. It is very strange.

List of Sources

Alexander, M. (2010). The new Jim Crow: mass incarceration in the age of colorblindness. New York: New Press ;.

Apidta, T. (2003). The Black Timeline of Massachusetts. Springfield, Ma: Tinga Apidta.

Hampden County Sheriff Department Ludlow Massachusetts. (n.d.). Hampden County Sheriff Department Ludlow Massachusetts. Retrieved December 9, 2013, from http://www.hcsdmass.org

Hooks, B. (2003). Rock my soul: Black people and self-esteem. New York: Atria Books.

Muhammad, K. G. (2010). The condemnation of blackness: race, crime, and the making of modern urban America. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

Neal, R. E., Benoit, J. J., & Collins, R. V. (1985). Status of Housing Inventory. Springfield, Ma: City of Springfield.

Welcome to Our City. (n.d.). City of Springfield, MA Official web site: Home. Retrieved December 9, 2013, from http://www3.springfield-ma.gov

_________________________________________________________________

Dominique P.

Reverend Dr. William N. DeBerry

DeBerry was a man of many talents. He excelled most in his talent for revitalizing a neighborhood, weaving the church and a neighborhood together. His skills were put to test when he became the pastor of St. John’s Congregational church in Springfield, MA. His ministry touched the lives of everyone in that community. Trying to empower individuals during a time period where they are constantly devalued and considered to be inferior is incredible task to take on. But DeBerry was one of those influential black men that rose to the challenge despite adversity. In 1899, he pastured that church with such strong conviction that gain help from other citizens to make outreach programs that aided the community.

DeBerry was a man of many talents. He excelled most in his talent for revitalizing a neighborhood, weaving the church and a neighborhood together. His skills were put to test when he became the pastor of St. John’s Congregational church in Springfield, MA. His ministry touched the lives of everyone in that community. Trying to empower individuals during a time period where they are constantly devalued and considered to be inferior is incredible task to take on. But DeBerry was one of those influential black men that rose to the challenge despite adversity. In 1899, he pastured that church with such strong conviction that gain help from other citizens to make outreach programs that aided the community.

The church was an important part of the African American community therefore its members and clergy always did their part to provide a sustainable environment for people of color. DeBerry helped to establish residence halls for women working as domestics while attending night school.

In 1911, he constructed a social services department called St. John’s Institutional Activities. This department oversaw the establishment of a library, a residential living space, and was a night school for women that tended to their homes during the day. DeBerry, extended his hand to anyone in need by helping incoming members into the community find housing. Along with being somewhat of an unpaid realtor, he also started an employment bureau in the church.

The successful development of his extensive community and outreach facilities became nationally known. One that is known to be oldest-continuously run summer camp for African Americans in the United States is the establishment named Camp Atwater. This establishment now has 75 acres of land and 40 buildings with a 3-acre island right off the camp’s main island.

“In 1924, DeBerry separated the social programs division from the church in order to bypass restrictions on the funding of religious programs. He resigned from the pulpit to lead the new organization, reorganized in 1931 as the Dunbar Community League, and the church itself languished for several years. It was reinvigorated in 1945 by the Reverend Albert B. Cleage, who began a program of Inter-racial City Wide Youth Conferences.” (Our Plural History Website)

He has been honored in Springfield having had an elementary school named after him, the William N. DeBerry Elementary School located on Union Street.

While there is very few information on Reverend DeBerry, the accomplishments that were documented demonstrate how inspiring an individual he was. His legacy was left in Camp Atwater and the many other facilities has started during his time in Springfield.

Edited by William N. DeBerry – Forge of Innovation

___________________________________________________________________

PRIMUS PARSONS MASON – For Consideration of Wikipedia Entry (Fall 2013)

Ivette P.

Primus Parsons Mason, an entrepreneur, real estate investor, philanthropist who was possibly a California pioneer during the Gold Rush FOOTNOTE/Gold Rush Stories: The Pioneer Valley and the California Gold Rush/, was born on February 5, 1817 in Monson, Massachusetts according to the Mason family’s old Bible (1). His parents, Jordan and Lurania Mason, were free people of color, and Primus was one of seven children. Upon his death, a newspaper headline (“Our Aged Colored Citizen who Left most of Property for Charity”) acknowledged his relative wealth and how he left most of his property or wealth to a charity organization he envisioned would be a home for aged men, in Springfield, Massachusetts (2)

Primus Parsons Mason, an entrepreneur, real estate investor, philanthropist who was possibly a California pioneer during the Gold Rush FOOTNOTE/Gold Rush Stories: The Pioneer Valley and the California Gold Rush/, was born on February 5, 1817 in Monson, Massachusetts according to the Mason family’s old Bible (1). His parents, Jordan and Lurania Mason, were free people of color, and Primus was one of seven children. Upon his death, a newspaper headline (“Our Aged Colored Citizen who Left most of Property for Charity”) acknowledged his relative wealth and how he left most of his property or wealth to a charity organization he envisioned would be a home for aged men, in Springfield, Massachusetts (2)

Born in Monson, Massachusetts, Primus Mason had little education, and was unable to write his own name until well past 40 years of age, according to some accounts (1)(2). Paul R. Mason, a former Springfield City Councilman, is a relative of Mason (3).

When he was seven years old, Primus Mason’s parents died and for five years was an indentured servant to Jonathan Pomeroy of Suffield, Connecticut, where according to W.E.B. Dubois, Primus worked as a farm hand. Primus ran away to Massachusetts and was apprenticed to a Monson farmer, Ferry. In 1837, Ferry’s son severely beat Mason which led to his running away once again. Legend has it that Ferry enlisted his own son to beat Primus so as not to pay the $12 due Primus at the end of his service since, by running away, his contract as an indentured servant, would be void (2).

At 20, Mason escaped to “Hayti” section of Springfield, Massachusetts. He worked as a pig farmer, and managed to find “work as a teamster and [dead] horse undertaker”. With the reliability of steady income through odd jobs such as collecting old shoe leather which he sold to the Springfield armory which was used to harden rifle barrels, and other menial tasks, Primus was able to make the first of many real estate investments. Daniel Charter, the seller of the property, in fact, loaned Mason the $50 to buy the property, which he paid back in full. The property was on the “north side of Boston Road” which today is in the Old Hill section of Springfield.

His family – the Masons – were originally from Monson and started migrating to Springfield, Massachusetts in the late 1830s, around the time Primus escaped to Springfield at 20, which in fact coincided with the underground abolitionist movement and a substantial number of African-Americans moving to Springfield from primarily southern states, which preceded the Civil War. In fact, African Americans from Connecticut began arriving in Springfield and surrounding towns soon after the Massachusetts State Constitution of 1780 was ratified, Connecticut kept slavery legal through 1782.

Opportunities for employment abounded which attracted many black individuals and families. Consequently, ambitious Black freemen, such as Mason, were able to thrive and succeed, making beneficial contributions to their communities. According to W.E.B. Du Bois, Primus Mason was “one of the chief Negro Philanthropists of our time” which benefitted the city of Springfield. By 1850, the Masons were an established Springfield family. The 1850 census listed Primus Mason as a farmer with real estate worth $1000.

While other Black freemen in Springfield, such as Thomas Thomas, became involved in the city’s underground abolitionist movement, Primus Mason was also a key player in the collective movement. A Springfield newspaper commented: “In abolition days, Primus Mason was one of the useful underground railway agents, receiving notice from Hartford allies when an escaping slave was on the road to this city and conveying the information to the Rev. Dr. Osgood, who looked out for the entertainment of the fugitive and sent him on toward Canada.” However, he is most known and celebrated for his energetic business acumen, acquiring real estate (including undeveloped property in the Hill section which later became the McKnight neighborhood). He often sold from his stash of real estate at a premium, and thus prospered. The city of Springfield was diverse and cooperative across racial lines, but some would say that the Black presence was essentially tolerated (?) albeit a spattering of and emerging antislavery cause. In the 1840’s and1850’s, Black Springfield produced leaders from within their own communities and Thomas Thomas was such a leader who aligned himself, as has already been mentioned, with the abolitionist movement, being a friend and colleague to John Brown. Both Mason and Thomas Thomas ventured out west during the California’s Gold Rush (well before the Civil War) and both men eventually returned to Springfield, Massachusetts after less than a handful of years.

It is not clear when Mason left for California’s Gold Rush but it is speculated he went “around the horn” of South American around 1858. While away, his wife Lucretia died. Mostly it is understood that he returned without any fortune to speak of, some say he was robbed and therefore returned to Springfield penniless. The Springfield Republican wrote: “He returned to Springfield without money, but with a decided experience in favor of consecutive enterprises, and his business life then forward illustrated what can be achieved by industry, prudence, foresight, and judicious investment in real estate.”

Census records of 1860 reveal that 276 Blacks lived in Springfield, Mass. At that time, Mason is 43 (page 6) of age, long having returned from out west during the Gold Rush. It is possible that with Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation which freed slaves in the south, Blacks prosperous and otherwise – including such men as Mason – sent money and clothes to family members in slave states. It is noted that the Black residents in Springfield, gathered at City Hall in celebration of the Proclamation. “All lovers of liberty” were urged to attend (?)

Du Bois also observed that Mason “had a sense of industry, prudence, foresight” which enabled him to succeed. Mason was “shrewd but honest, as his means enabled him”. Throughout Mason is acknowledged to be a successful, if clever, business man with the necessary acumen to recognize the value of properties he continued to purchase in the Old Hill area. He was respected by the community and by 1888 (at age 71), was one of the wealthiest citizens of Springfield. In fact, a humorous nugget involves him purchasing property which was of interest to the Monson farmer Ferry, to which he was indentured as a child, and selling it at considerable profit to himself.

Primus Mason and his family live on State Street in Springfield. A nearby street would eventually be named in his honor. Interestingly, he is reported to have had numerous wives, all of which he outlived. Only one daughter, Emily, resulted from these various unions. However, in 1873, at age thirty-four, she passed, childless.

In 1888, Primus suffered a setback when his barn on set on fire whose blaze grew beyond the scope of what the fire department was able to handle. Even with the loss of the property, Primus was able to save three horses, two cows, six carriages. His losses in the blaze included four tons of hay and farm equipment totaling $1500; thankfully, he had insurance. The local paper reported that William Sharp was to be tried in court for setting the fire but, apparently, there was a hung jury and the case was dismissed.

In Efforts for Social Betterment Among Negro Americans (1909), DuBois (1) notes “Few races are among instructively philanthropic than the Negro. It is shown in everyday life and in their group history”. DuBois goes on to discuss Mason as one such individual. Primus Parson Mason was “one of the chief Negro Philanthropists of our time” (footnote, Social betterment/DuBois) which served Springfield, Massachusetts, a community that was home to both Mason and his extended family. Mason is quoted as saying he wanted to leave behind “a place where old men that are worthy may feel at home”.

Upon Mason’s death on January 12, 1892, he certainly assured his status as the most prominent member of his family in the 19th century. His estate, in fact, did fund a Springfield Home for Aged Men which continues to exist today, in the 21st century. DuBois (1) notes “[that] the foundation for a charity like this has been laid by one man, demands that some notice of his life be placed among our records”. At the time of his death, Mason has real estate property valued at $23,400, his net value being $29,451. However, the newspaper (?) which acknowledged his death note “It was a surprise to everybody that Primus Mason, who died last week, left a property, mostly in real estate, worth some $40,000. It notes that in addition to finding a home for aged men, he left $2000 to the Union Relief fund for aged couples”. That same article offers Mason the dubious honor of being a reliable businessman, “industrious and thrifty when so many were idle and slack, temperate and honest, but shrewd and calculating”. It is written he quietly paid “many a poor colored man’s funeral expenses”. While it is suggested he was married more than once, his latter years, it is claimed, were lonely, “without intimates of his own family”. It is this last sentiment that perhaps led to his desire and self-appointed duty to found “a place…for worthy old men may feel at home”. The home for aged man was open to any race since Mason “made no discrimination in race or color in this his principal charity”. Today, this home, Mason Wright, is still in existence, primarily serves non-Black individuals and few, if any, know that its founder was an accomplished and prosperous Black man who prior to the Civil War was a leader and free man in Springfield, Massachusetts. In the spirit of Primus Mason’s wish they note on their website “Our mission is to provide quality housing and daily living services to support the dignity and independence of seniors without regard for their ability to pay.

(1) Efforts for Social Betterment Among Negro Americans (1909), W.E.B. DuBois

(2) Gold Rush Stories. The Pioneer Valley and the California Gold Rush – Primus P. Mason: Springfield Benefactor. Courtesy of Museum of Springfield (MA) History.

(3)

(4) Black Families In Hampden County, Massachusetts 1650-1865. Second Edition, Joseph Carvalho III. New England Historic Genealogical Society 2011.

(5) Our Plural History – Springfield, MA. Resisting Slavery: Primus Mason. Springfield Technical Community College, 2009. ourpluralhistory@stcc.edu.

(6) At the Crossroads: Springfield, Massachusetts 1636-1975

(7) Springfield’s Ethnic Heritage: The Black Community. An Interpretation of the Black History of Springfield, Massachusetts – from the mid 1600s through 1940, by Jeanette G. Davis-Harris. American Bicentennial Celebration1975-1976. U.S.A. Bicentennial Committee of Springfield, Inc., 1976.

_____________________________________________________________

Community Engagement with members of the Roger L. Putnam Vocational Technical Academy Boys Basketball team

Springfield Engagement Project

With gratitude to Coach William Shepard, the 2013-2014 Putnam Boys Basketball Team, Assistant Principal Kyngelle Mertilien-Tinson, Dr. Trevor Baptiste, and Edward Cage.

___________________________________________________________

Makayla L.

Dr. Ruth B. Loving (born 27 May 1914) is an extraordinary woman that, at the age of 99, remains energized by her passion for equality. She has been referred to as the first lady or mother of Springfield’s Civil Rights Movement because of her social activism over the years. She retrieved this name after she served as President of the local chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People in the 1960’s and her founding of what was the Springfield Negro Post. She has based her life around getting people to get involved in helping their neighbors because “even the smallest acts of kindness build over the years.”[1]

Early Life and Education[edit]

Ruth B. Loving was born on May 27, 1914 in Phoenixville, Pennsylvania. She was taught the importance of family and unity from a young age, being the youngest of seven children. In 1918, when Loving was around four years old, her family moved to New Haven, Connecticut. The First World War was in full effect and Loving’s father saw it as a job opportunity to work in the Winchester gun factory making guns for the United States Army. It was around this time that Loving was exposed to the realities that were taking place around her. She began noticing the large numbers of black folks who were migrating from the South. After hearing stories about how black people were treated in the South, she was given her first understanding of discrimination. However, it wasn’t until she got older that she learned about the separation of races and the intensity behind the color line.[2]

While in the sixth grade at the Gregory Street School, Loving decided to join the Fife and Drum Corps. She had an interest in music and wanted to learn how to play the fife. During this time, the Fife and Drum Corps was primarily for boys but Loving was determined. After meeting with the principal, Loving became the first and only girl in her school to participate in the corps. This was the start of her love for music. Faith and religion were essential aspects within her family dynamic. Going to church every Sunday was a must, but this didn’t bother Ruth because she became fascinated by the sound and music produced from the organ. This fascination fueled her determination to learn how to play the instrument that brings people faith and joy. It’s wasn’t long before she was playing the organ and participating in the youth choir.[2]

When Loving was fifteen, she was introduced to the NAACP. Loving’s mother was an active member of the NAACP and would save the little money she could to pay her membership dues. Ruth’s curiosity led her into asking what the NAACP was. Her mother then told her it was a new organization that was forming to help black people live a better life. Loving knew right then that it was something she wanted to be a part of. She gathered her pennies and joined the youth membership of the NAACP. This membership allowed her to attend the meetings and get a better understanding of what was happening in the world. Becoming a youth member was a foreshadow of her potential within the organization.[3]

Career and Personal Life[edit]

Although education was an important aspect of Ruth’s life, music always seemed to more appealing. While in high school, she had to learn a foreign language. She selected French because she enjoyed listening to French music and was intrigued by the romanticism. As her high school career came to an end, Loving aspired to become a singer. Once she turned eighteen she went to New York. She had heard about a night club that two Jewish brothers were opening and wanted to become an entertainer. She originally planned on auditioning to be a singer but when she got there they were only holding auditions for dancers; she saw an opportunity and went for it. She ended up being one of the women chosen; which was surprising and revolutionary because she was a woman of color that was chosen to dance in a white club. The dancers practiced vigorously over the summer months in preparation for its opening day in September. When she got the costume she was supposed to wear on stage she immediately thought of her mother’s disapproval. The costume consisted of a bra, panties, and feathers. Loving’s older sister, Lillian, was granted permission to attend the show. Once she saw Loving in her costume her mouth dropped. After the show, Lillian told Loving that she needed to quit and go home being this wasn’t a decent job for a lady. Despite the amount of money she was making, Loving packed her bags and returned to Connecticut.[4]

Shortly after returning home, Loving met her husband: Minor Loving. It wasn’t long before they got married and moved to Boston. Minor Loving had been working for a dry cleaning business that owned facilities throughout the United States. While in Boston, Minor Loving saw the talent his wife possessed and pushed her to get an entertainment license so she could sing as a profession. In 1939, Minor Loving was transferred and they had to move to Springfield, MA. One of the first things Loving did once arriving in Springfield was join the local branch of the NAACP.[5]

At the start of the Second World War, Loving felt the urgency to contribute in some way. She was informed of a pick-up system that brought entertainers to the soldiers at Westover Field in nearby Chicopee, MA, which was established as an Army Air Corps airfield in 1939, and had them perform. This was the making of the United Service Organization (USO). Loving jumped at the opportunity and became one of the first entertainers in the World War II homefront. This eventually led her to join the Massachusetts Women’s Defense Corps in 1943, the first Massachusetts National Guard unit for women. The National Guard was in need of women who could take care of officers, communication, paperwork, etc. and Loving graciously took on the responsibility. Loving quickly proves her determined work ethic; she starts off doing typing and administrative work then gets promoted to military communications. Through this she learns Morse Code and is stationed to work in a secret facility in Springfield, which served as the region’s military communication center.[6]

In 1945, Loving becomes a mother to her first child; a son she named Minor Loving Jr. Shortly after her and her husband have two more children, Anthony Floyd Loving and Holly Ruth Loving. Loving and her husband raised their children the best way they knew how. They decided to put their children in dancing school, which is very unusual for black folks, as a tool for something they could potentially do as a profession. This tool eventually led to the making of the Loving Trio. Once the Korean War began, Loving again volunteered to participate at the USO shows. Except this time she brought her children along with her. Loving sang while her two boys tap danced and Holly danced ballet. The Loving Trio performed so well that they began entertaining on a regular basis, which they did for the next six years.[7]

Political Activism[edit]

When her eldest son, Minor Jr. goes to Chester Street Junior High in Springfield, Loving is disturbed to find out that there is not a Parent Teacher Association (PTA) at the school. Loving understood the importance of education and wanted to be a part of her children’s learning experiences. She decided to take matters into her own hands and marched over to the city council where she requested for a PTA to be organized. Through her petition, a PTA was established and Loving was elected to be its first president.[8]

Loving’s need for change didn’t stop at the school system. In the 1960’s, she became president of the NAACP branch in Springfield. She made it a point to contribute to the Civil Rights Movement in any way possible. Loving and the other members of the NAACP gathered up any money they could and sent it to Martin Luther King Jr. to help with the work he was doing. She was able to organize a local rally and get enough money to have Rosa Parks travel to Springfield to talk about the things she was going through and the things that were happening in the South. She also encouraged the youth members to take a stand. With the support of the NAACP in Springfield, many youth members who attended college participated in the marches and protests. Although she wasn’t the most prominent activist in the Civil Rights Movement, she remained determined and did whatever she could to help. Her enthusiasm for equality motivated the people around her to take action as well.[9]

After the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. in 1968, Loving works with local churches and parishes to establish a citywide choir to sing at his memorial tribute. The choir was named “Pastors’ Council Choir” and attracted more than two hundred members; who sang the memorial celebration of Martin Luther King Jr.’s life held in the Springfield Symphony Hall. The choir is still active today, under another name: “The Freedom Choir.” Loving has continued to participate in the choir and is currently the choir secretary.[10]

Loving has also been very active in making a change towards the inequality that takes place regarding housing and senior citizens in Springfield. In 1995, Loving became a delegate to the White House Council on aging under the Clinton Administration. She is currently on the board of Springfield Council on Aging and has served as the African American Senior Activity Center committee president for the past few years. In 1996, Loving began working as a radio announcer on the talk show “Spotlight on Springfield.” Two years later, Loving organized a movement to have the Black American Heritage flag, which she created, flown in front of City Hall during Black History Month.[11]

In spite of the activism work Loving has participated in, she made it a point to receive higher education. In 1987, Loving achieved her dream of a college education and graduated from the University of Massachusetts Amherst with a Bachelor’s Degree in Community Education and Media. Also, in 2004, as a recognition for her contributions to her community and her achievements, Loving was awarded an Honorary Doctor of Humanities Degree by the Springfield Theological Society.[12]

Dr. Ruth B. Loving’s energy, passion, and faith for a better world is something that transcends, not just through her community but through the nation.

References[edit]

- Jump up^ Rodriguez, Elysia. “Ruth B. Loving Honored in Springfield”. Retrieved 28 February 2012.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “Dr. Ruth B. Loving – 1914-1929: World War I and the Great Migration”. Ruth’s Childhood Memories. Pocumtuck Valley Memorial Association. Retrieved 1999-2013.

- Jump up^ “Dr. Ruth B. Loving – 1914-1929: World War I and the Great Migration”. Ruth’s Childhood Memories. Pocumtuck Valley Memorial Association. Retrieved 1999-2013.

- Jump up^ “Dr. Ruth B. Loving – 1941-1945: The USO, and the Massachusetts Women’s Defense Corps”. Ruth Loving’s Service During World War II. Pocumtuck Valley Memorial Association. Retrieved 1999-2013.

- Jump up^ “Dr. Ruth B. Loving – 1941-1945: The USO, and the Massachusetts Women’s Defense Corps”. Ruth Loving’s service during World War II. Pocumtuck Valley Memorial Association. Retrieved 1999-2013.

- Jump up^ “Dr. Ruth B. Loving – 1941-1945: The USO, and the Massachusetts Women’s Defense Corps”. Ruth Loving’s service during World War II. Pocumtuck Valley Memorial Association. Retrieved 1999-2013.

- Jump up^ “Dr. Ruth B. Loving – 1945-Present: The Loving Trio and Ruth’s Civilian Life”. Pocumtuck Valley Memorial Association. Retrieved 1999-2013.

- Jump up^ “Dr. Ruth B. Loving – 1945-Present: The Loving Trio and Ruth’s Civilian Life”. Pocumtuck Valley Memorial Association. Retrieved 1999-2013.

- Jump up^ “Dr. Ruth B. Loving – 1945-Present: The Loving Trio and Ruth’s Civilian Life”. Pocumtuck Valley Memorial Association. Retrieved 1999-2013.

- Jump up^ “Timeline of Dr. Ruth B. Loving’s Life”. Pocumtuck Valley Memorial Association. Retrieved 1999-2013.

- Jump up^ Stephens, Samantha. “Ruth Loving at 97: Springfield’s Mother of Civil Rights”. Retrieved 4 February 2012.

- Jump up^ Stephens, Samantha. “Ruth Loving at 97: Springfield’s Mother of Civil Rights”. Retrieved 4 February 2012.

Rachael P.

Arise for Social Justice: Then and Now

I visited the Arise office last week to get a first hand, face-to-face account of Arises’ early days. Michaelann Bewsee, the current director of Arise for Social Justice was happy to speak with me. She kicked off the conversation by saying “Arise for Social Justice was started by myself and three other women on welfare.” She went on to offer a lively and engaging tale of its development. I was unable to transcribe the conversation, and a recording would have been preferable. Speaking with her turned out to be far more useful than any of the written records I looked through. Moreover, it was actually interesting.

I visited the Arise office last week to get a first hand, face-to-face account of Arises’ early days. Michaelann Bewsee, the current director of Arise for Social Justice was happy to speak with me. She kicked off the conversation by saying “Arise for Social Justice was started by myself and three other women on welfare.” She went on to offer a lively and engaging tale of its development. I was unable to transcribe the conversation, and a recording would have been preferable. Speaking with her turned out to be far more useful than any of the written records I looked through. Moreover, it was actually interesting.

In 1985, the battle over the state budget was in full swing, with Governor King in office. “He was the last independent governor elected here”, she said. Similar to what we recently experienced with the government shutdown, everything was at a halt because of the disagreement. State employees were being paid, but there was no money coming from the federal government. “The well-organized and thoroughly ticked off unions workers fought back very quickly, it took the community a little bit longer.” A huge percentage of the community was suffering from this political disagreement. At the time, half of welfare came from the state while the other half was federal money. Therefore, people were only getting half of the benefits that they qualify for. From what I understood, this is the incident that catapulted Michaelann to do something big. She was sick and tired of watching Springfield’s poor population take the brunt of unfair rules and social stigma.

Michaelann told me that her first step was a phone call to the Coalition for Basic Human Needs in Boston, in hopes of gaining organizing insight and funding ideas. CBHN explained they did not have the resources to come out and help, but gave her phone numbers of people who may be interested in funding her cause. Desperate to get the organization on its feet, Michaelann made a phone call less than five minutes later that would benefit the lives of low- income Springfield residents in ways that nobody imagined.

Springfield Action Commission was the only anti-poverty group in the area at the time and asked the founding members if they would like funding to do welfare rights organizing. Michaelann’s face lit up when she got to this part of the story. She spoke about it like it was a cherished moment of her life. They offered to fund her project before she even asked.

In January 1985, Cindy Montoya, Karen Rock, Michaelann Bewsee and Terry Winston held what would be become the very first meeting of Arise for Social Justice. “People caught on quick! It was just so empowering to see the community coming together over something that had been eating at me for years,” said Michaelann. We wanted to spell out a clear mission of what we stand for and how we were going to execute it. The original goal was just around issues of welfare. The women were frustrated with the exhausting rules and regulations of government aid, as well the misrepresentations surrounding mothers on welfare. They met in the run-down back room of Springfield Project for United Neighbors office on Hancock St. They got the OK from the director, which she attributes to the organization fizzling out. She said they were “on their way out” when Arise started meeting.

Within a few months they had enough money to afford their own office space. They formed a coalition with Springfield Housing Authority and Western Massa Legal Services, which “were far more radical at the time than they are now”, said Michaelann. Unfortunately, as wealth inequity has escalated over the last 25 years, the service agencies to assist people have become more conservative. Michaelann explained that there is an increasing “de-radicalizing” effect from neoliberal ideologies on social service agencies. Both of these organizations are still up and running, though their collaboration with Arise would be nothing short of a miracle at this point. As Arise has radicalized over the years they have formed some enemies around the city. Most of the social service agencies operating in Springfield end up as the brunt of Arises frustration, and police enforcement is not exactly on their side.

The first campaign was around a law passed regarding child support for mothers on welfare. In late spring of 1985, Women for Economic Justice was working towards an increase in welfare benefits as well, so they collaborated with Arise to organize their very first event. They held a big rally downtown on Main Street, and the outcome far exceeded any of their expectations. The event ended up making the front page of the newspaper, as large numbers of community residents could identify with the cause. Michaelann said that she was “scared shitless” to speak publicly in front of so many people. It was really surprising while at the same time comforting to hear this. At 67 year old, she is such a confident and well-practiced public speaker. Her honesty was both refreshing and humorous. She has really developed her skills over the years. She gave me hope that fear of public speaking really can diminish!

Within the first few years of operation Arise had expanded the mission beyond the narrow focus of welfare rights. For example, they realized the severity of homelessness in the city and expanded the mission to include accessibility to affordable housing. Today, Arise is willing to organize around any issue that affects the low-income residents and homeless people of Springfield. Listening to Michaelann give such an engaged and thoughtful tale of Arises’ history provided immense insight. She had a vision and she made it happen with what she calls “determination, and a little but of luck”.

I was fortunate enough to get my hands on a couple of documents that Arise had stored away. The first, a city document full of poverty/ housing statistics and analyses in the city between 1975 and 1985. I figured this source would be especially useful as it illustrates Springfield’s poverty problem in the decade leading up the founding of Arise. It shows housing inventory as it existed before implementation of the Housing and Community Development Act of 1974, and after in 1985. Housing trends are in great detail.

The most visible issue I noticed in the statistics was the racial segregation based on neighborhoods. There were virtually no mixed race neighborhoods. Unfortunately, the issue of racial segregation in the city of Springfield is no different today. The only neighborhoods that are predominantly white are Forest Park, Pine Point, and Sixteen Acres. I know that as a result of the racial segregation by residence, the elementary schools are overwhelmingly segregated. Most of the elementary schools are all white or all minorities. Not until High School are students fully integrated with the entire scope of socio-racial-economic backgrounds. There are four of them, and students can make their pick.

Arise for Social Justice: What is it like Today?

Today, Arise for Social Justice is a low-income rights organization ‘run by and for the poor.’ Arise believes that society deliberately ignores the needs of the poor through the socio-political and economic institutions. The mission of Arise is to build political power from the bottom up for the systematically silenced voices of low-income Americans.

Arise for Social Justice believes that together, the low-income community of Springfield, ma has immense potential power for social change but that lack of solidarity stands in the way. Arise for Social Justice does its work on the fundamental premise that that the large majority of people living in poverty are unaware of the systematic injustices that affect them and see their problems as individual issues. Many are under and misinformed of their rights and do not participate in decision making processes within political life for a number of reasons whether it be lack of information, denial, hopelessness or despair.

Arise works to connect the dots from these exploitative structures to the day-to-day hardships of poverty so that people can learn to advocate for themselves and each other. Arise sees itself as a refreshing escape from the exhausting, frustrating, and often times dehumanizing realities of American poverty. Arise is a place for people discouraged with their lives amidst the bureaucratic nightmare that is the social service system.

On this premise, Arise organizes to fight back against the racial and socio-economic injustices inherent to the institutions that make up American society. Some of Arise’s methods of resistance include, protests, rallies, auction blockades, marches, informational pamphlets, free community events, and much more.

Arise sees itself as a “social change” organization, in that it is constantly organizing to affect political/institutional change while simultaneously navigating people through the exhausting, frustrating, and disheartening day-to-day problems of the social services they are caught up in.

Arise assists people with welfare forms, housing applications, sealing CORIS, etc, while at the same time taking measures to reform these services. The day-to-day accomplishments of Arise include everything from getting a family into shelter, stopping a foreclosure, or protesting food stamp budget cuts, to the small feats of feeding the hungry or providing a ride to the doctor, therapist, grocery store, etc. Arise advocates for any and every issue that affects low-income communities including homelessness and affordable housing, climate justice, education, mass incarceration, welfare and other social service programs, domestic violence, and more. Currently, Arise is part of a national housing campaign called “Homes for All”, a national movement of organizations ready to fight for, and win, affordable and accessible housing for all. At the same time, Arise is working locally on this issue through S.U.N.N., a local movement made up of Springfield residents organizing for housing rights. Together, S.U.N.N. hopes to reform unfair housing policies in the city.