Melanie Griffith, Ji-In Jeong, Maggie North, and Juliana Ward

Curatorial Statement

Direct and accessible, drawing more than any other medium offers a window into the artist’s process. The drawn line echoes the movement of the hand, and seems by extension to trace the meanderings of the artist’s thoughts. Like a ghost of a passing feeling, memory, or movement, the expressive line appears urgent, essential, gestural and private. In the 20th century, Expressionist and Abstract Expressionist artists rejected the rigid hierarchy and naturalistic drawing style promoted by the academy and embraced experimental images that challenged traditional drawing aesthetics and materials. This exhibition explores drawings by modern and contemporary artists who created a new, expressive line-based language. These innovative lines arrived in many forms as is evident in the variety of mark-making techniques, materials, and shapes that make up the works on view. These artists used the expressive line as a code to signify a variety of meanings, ranging from the observational to the personal and political. In this exhibition, the expressive line transforms and transcends, to speak beyond the private and conventional foundations of drawing.

Using the expressive line, these artists employed new techniques and concepts, and thereby expanded the definition of drawing. When placed in their historical context, the works in this exhibition claim line as an expressive tool, rethinking its academic use. Politics of the personal and cultural have become essential to contemporary artists who are still experimenting with, reinventing, and appropriating the expressive line. Expressive drawing in our contemporary era challenges our values, resists oppression, and expresses beyond conventions.

Organization of Exhibition

This exhibition will be divided into four sections. The first section, Espressionist Modes and Methods explores the tension between two giants of modern abstraction: Wassily Kandinsky and Aleksandr Mikhailovich Rodchenko. Both artists were interested in a radically new aesthetic that could express the ideas of the modern era, yet the two disagreed about their methods and intentions. While Kandinsky’s fluid abstractions were inspired by music or nature, Rodchenko used tools, like the compass, to create purely non-objective, geometrical compositions. The second section, Life Drawing and Distortion, explores the way that coded lines play a part in semi-figural, expressive life drawings. Many artists used gesture and distortion to depict a version of the body that is informed by, but breaks with academic tradition. The artists represented in this grouping aimed to move beyond the surface of figural images, delving into human psychology and imagination. The artwork in Myriad Marks toes the line between recognizable and unrecognizable forms. It presents a variety of lines, both organic and geometric, that both reveal and hide their meanings. The exhibition closes with work by American Abstract Expressionist artist who drew inspiration from emotions and materials rather than from nature.

Checklist and Wall Labels

Section 1: Expressionist Modes and Methods

Wassily Kandinsky

(Russian, 1866-1944)

Abstract Composition, 1916

India ink, pencil on sketchbook paper

13 1/2 x 10 in.; 34.3 x 25.4 cm

Gift of Thomas P. Whitney (Class of 1937)

Mead Art Museum, Amherst College, AC 2001.104

Ji-In Jeong:

Wassily Kandinsky was a Russian-born theorist and pioneer of the German Expressionist movement. He was deeply affected by the militarized and nationalistic political landscape in Germany in 1914. He believed that art could create a parallel to the motions of the cosmos. Kandinsky attempted to translate the unique experience of synesthesia into visual art, suggesting the vibrations of symphonic music in his use of line and color. In Abstract Composition, he suggests a bodily space with fluid lines that range from thick and thin. The india ink lines contain shaky movements, leaving no part of this composition still or certain. The smaller strokes scattered throughout the page mimic an organic form, suggesting the texture of grass or scenes from nature. Unavoidable to the eye is the thick, black diagonal line, centrally place on the page. It serves as a guide to the whirlwind of information that Kandinsky chaotically scatters within this shaky world. He challenges the conventions of artistic practice by attempting to relay the unseen vibrations of the world.

Aleksandr Mikhailovich Rodchenko

(Russian, 1891 – 1956)

Compass Composition, 1915

Pen and ink and black ink on medium weight soft, textured off-white paper

6 15/16 x 10 5/16 in.

Gift of Thomas P. Whitney (Class of 1937)

Mead Art Museum, Amherst College, AC 2001.76

Melanie Griffith:

Aleksandr Rodchenko’s artwork created new possibilities for modern art. His pieces following the Russian Revolution 1917 are marked with the bold statement that painting was dead, ushering in a new era of Constructivism. Later noted for his photography, he was also a skilled abstract painter, producing works that broke with the traditional techniques of easel painting. Even before the period of Revolution and civil war that would soon reshape Russian society, Rodchenko had already broken with traditional academic art and entered the world of abstraction. His piece boldly uses the design technology of the compass to develop a playful expression using geometric forms.

In the beginning, Rodchenko was influenced by the works of Wassily Kandinsky. But Kandinsky’s art, though abstract, tended to point back toward figurative sources, relying on symbolism and psychology, whereas the younger generation focused on the purely abstract.

Section 2: Breaking with the Academy:

Life Drawing and Distortion

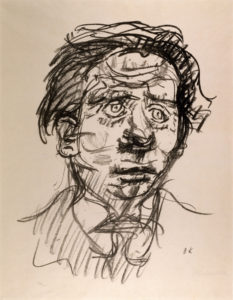

Oskar Kokoschka

(Austrian, 1887-1980)

Max Reinhardt (Head), 1919

Lithograph on grey wove paper

Demensions unavialable

Gift of Priscilla Paine Van der Poel, class of 1928

SC 1977:32-169

Maggie North:

Although it is a lithograph, the urgent and disorderly lines in this print call to mind the act of sketching. With erratic marks, Oskar Kokoschka has captured his contemporary, the famous film and theater director Max Reinhardt (1863–1943), in a state of apparent anxiety. After breaking with the School of Arts and Crafts in Vienna, Kokoschka became known for portraits that, in his words, “intuit from the face, from its play of expressions, and from gestures, the truth about a particular person.” Kokoschka was playwright, poet and visual artist, but he was also interested in psychology. Working in an era when influential psychoanalytic writings by Sigmund Freud were widely published, Kokoschka believed that a person’s “truth” existed in their interior world and sought to expose it. In this portrait, Reinhardt’s impossibly round, asymmetrical eyes and elongated, furrowed brows are expressive rather than naturalistic.

Leonard Baskin

(American, 1922 – 2000)

Two Men, 1953

India ink and graphite on buff laid paper

38 1/8 in x 25 1/8 in

Gift of Helene B. Black (class of 1931)

MH 1988.14.17

Maggie North:

Inspired by the fragility of the human condition, Leonard Baskin’s depictions of the human figure are often distorted or disfigured. He once stated, “The human figure is the image of all men and of one man—it contains all and can express all.” As in Two Men, Baskin’s approach to the human body is informed by knowledge of musculature and the academic study of proportion, but Baskin breaks the academic rules. Heavily shaded in some areas and sparsely sketched in others, his bodies are scattered with dark, angular marks that could represent veins or scars rather than smooth, supple skin. The unsettling postures and mysterious facial expressions of the men depicted contribute to the expressive quality of line in this drawing. Represented in numerous museums and private collections, Baskin is known internationally, but he also had a local presence. The artist taught art at Smith College from 1953–-1974, then at Hampshire College from 1984–-1994.

Henry Spencer Moore

(British, 1898-1986)

Untitled: Female Figures, 1956

Pencil, pen and ink, crayon and colored wash

10 15/16 in x 7 1/4 in

Gift of Richard S. Zeisler (Class of 1937)

Mead Art Museum, Amherst College, AC 1959.139

Ji-In Jeong:

Henry Moore primarily worked in sculpture, but used drawing as a means of quickly expressing ideas from his unconscious. Moore blended human figures and other observations from the natural world to abstractly construct his drawings, often employing a variety of mediums to render two-dimensional images which would later be translated into sculpture. In Untitled: Female Figures, the artist creates the illusion of a sculptural work through the use of line, contour, color, and materials. He highlights certain areas with a vibrant wash of color and leaves others white, playing with positive and negative space. To complement these lighter areas, Moore layers on a variety of textured tonalities, from the subtle shading of the graphite pencil to the stark black ink used to render the darkest hatched areas. Moore uses line to push his imagined forms into a third dimension. Drawing serves as a mode of accessible and swift expression that can later be processed into a sculptural form.

Section 3: Myriad Marks

Harvey Quaytman (American, 1937-2000)

Harvey Quaytman (American, 1937-2000)

Cinzano, 1963

Pencil and oil crayon on paper

11 1/16 in x 14 in

Gift of the artist in memory of his father, Mark Quaytman. University Museum of Contemporary Art, University of Massachusetts, Amherst, UM 1963.3

Ji-In Jeong:

Harvey Quaytman was a New York based geometric abstract artist known for his signature hard-edged painting style related to Minimalism. His work also combines an expressive language with asymmetrical compositions and rich areas of colors. In Cinzano, lines of varying thicknesses, shapes, and flexibilities interpret geometric forms within an abstract plane. The title comes from an iconic Italian vermouth, suggesting that the artist worked from a direct observation of the bottle in order to redefine the traditional conventions of a still-life image. The main compositional lines are thick and confident. Secondary scribbled or hatched lines have a more fluid motion to them, floating through a suggestion of shallow space. Some lines are created negatively by erasing, while others are thickly applied through heavy handed shading, as seen in the rectangular block on the left side of the page.

Barbara Hepworth (British, 1903-1975)

Project for Wood and Strings, Trezion II, 1959

Painting, oil, gesso, pencil on board

14 7/8 in x 21 1/8 in. Gift of Richard S. Zeisler. Mead Art Museum, Amherst College, AC 1960.1

Juliana Ward:

Barbara Hepworth, an internationally recognized British sculptor, is known for her abstract sculptures that evoke nature using line, shape, space, texture, and natural materials. This sketch for a sculpture, Project for Wood and Strings, Trezion II, provides a glimpse into Hepworth’s obsession with form, through the precise and almost mathematical lines she employs in pencil over a tonal painted background. These graphite lines come forth to create abstract shapes as they rotate and attach to each other, suggesting tensions of three-dimensional space. The hatched diagonal lines in the center of the brightest blue tone create a vanishing point alluding to the tradition of perspective drawing. Hepworth reinvents perspectival space through futuristic abstraction. She utilizes abstract line to re-envision the sketch in this ethereal drawing.

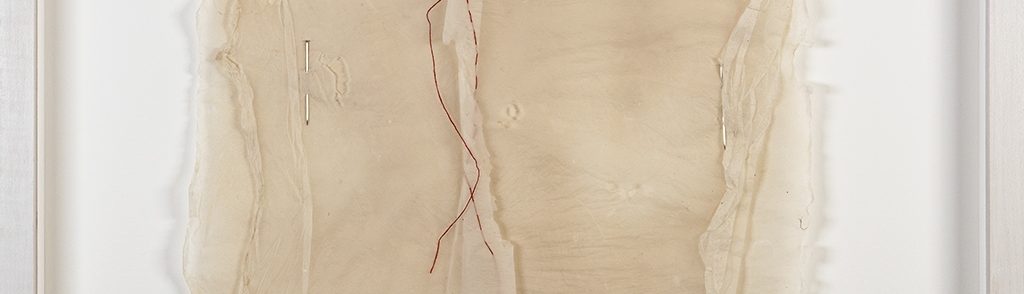

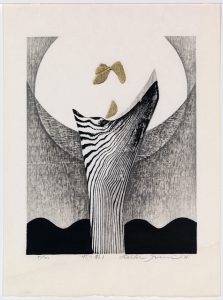

Iwami Reika

(Japanese, b.1924)

Untitled “Skating by the Water”, 1976

Print, woodblock and gold leaf

13 3/4 in x 10 1/16 in.

Gift of Doris Lee and John H. Rich, Jr. Mead Art Museum, Amherst College, AC 2010.31

Juliana Ward:

Iwami Reika, a Master Japanese printmaker, is known for her abstract linear evocations of nature. She reinvents the capabilities of the expressive line through incorporating found materials into her print. Reika not only relies on her own hand to render line but uses found driftwood, both printing the natural wood grain and using it as inspiration for organic drawn lines. Her expressive language of line blurs the divisions among natural elements such as water, wood, air, and space. Working in a limited color palette, Reika allows line, space, and visual texture to take center stage. Her emphasis on the expressive and sometimes symbolic line or shape creates a restrained drama, suggesting a philosophical or spiritual inner world. Reika is also a poet of haiku, another Japanese tradition based on restraint. She states, “Haiku is a discipline study. It forces one to eliminate what is not necessary, and that’s why I use it as a spiritual exercise for my prints.”

The Expressive Line as Gesture

Lee Krasner

(American, 1908 – 1984)

Primary Series: Gold Stone, 1969

Color lithograph

22 1/2 in x 30 in.

Gift of Robert Staub through the Martin S. Ackerman Foundation, University Museum of Contemporary Art, University of Massachusetts, Amherst, UM 1979.23

Lee Krasner

(American, 1908 – 1984)

Primary Series: Pink Stone, 1969

Color lithograph

22 1/2 in x 30 in.

Gift of Robert Staub through the Martin S. Ackerman Foundation, University Museum of Contemporary Art, University of Massachusetts, Amherst, UM 1979.24

Lee Krasner

(American, 1908 – 1984)

Primary Series: Blue Stone, 1969

Color lithograph

22 1/2 in x 30 in.

Gift of Robert Staub through the Martin S. Ackerman Foundation, University Museum of Contemporary Art, University of Massachusetts, Amherst, UM 1979.25

Melanie Griffith:

Lee Krasner’s Primary Series presents a compelling spatter of color on canvas. The triptych is based on the primary colors, but replaces the common red, yellow, and blue with more suggestive or poetic hues. Krasner became known for the colorful and exuberant paintings she produced after the death of her husband, painter Jackson Pollock, in 1956. Empowered by the women’s movement, she charged ahead, creating paintings and prints renowned for their dynamic and colorful expression. She experimented with a wide range of different techniques of putting color down on canvas and paper. In this three-part series, Krasner renders homage to Pollock’s drip paintings, experimenting with transparency and opacity achieved by varying the thickness of the lithograph ink before printing each image in her chosen color.

Joan Mitchell

(American, 1926-1992)

Sides of a River I, from Bedford Series, 1981

Lithograph printed on color paper

42 x 32 in.

Gift of Lois Perelson-Gross, class of 1983, and Stewart Gross in honor of Janice Carlson Oresman, class of 1955, on the occasion of her 50th reunion

SC 2005:12-1

Maggie North:

Joan Mitchell was one of only a handful of female artists to break into the male dominated American Abstract Expressionist group in the 1950s. Although she is celebrated for her large, colorful, action paintings, Mitchell also used pastel and was an accomplished printmaker. At first glace, her marks may seem unplanned, but extraordinary attention to balanced color schemes and the figure-ground relationship typically underlie Mitchell’s gestural works. In 1981, Mitchell worked closely with renowned printer Kenneth Tyler to create a series of ten large lithographs, including this one. The series was titled the “Bedford Series,” after the workshop’s location in Bedford Village, New York. Scattered, chalky, semi-vertical marks fill center of the composition, becoming darker and more condensed at the top and bottom of the paper. Mitchell’s compressed lines are nearly calligraphic. Like illegible signatures, they simultaneously invite speculation and hide their expressive meaning.