Stephanie Choi, Caitlin Green, Sofia Pitouli, and Charlotte Seaman

Thread Up brings together ten contemporary female artists from the Five College Collections who are intentionally applying materials and techniques traditionally associated with women’s experience. These artists incorporate materials or mimic the qualities of materials such as thread, quilts, lace, and textiles, and use them to make greater statements on femininity, religion, politics, and race. The drawing materials are linked to evolving interpretations of “women’s work,” emphasizing a gendered tradition, while simultaneously subverting and politicizing the use of materials.

Judy Chicago, American (b. 1939) Emily Dickinson Plate (study), 1977

China paint, lace, and ink on porcelain plate, 14 in.

Gift of J. Thomas Harp

Mead Art Museum, Amherst College, AC 1995.21

Judy Chicago is a revolutionary American artist known for her poignant and sharp Feminist artwork. She is best known for her sculptural installation titled The Dinner Party, a large triangular banquet table with 39 place settings, each honoring a different historical woman. The work seen here, Emily Dickinson Plate, is a study for the final plate in the installation, now located in the Brooklyn Museum. The juxtaposition of the vaginal design in the middle and the delicate, feminine lace surrounding reflects the strictness of Victorian culture for women, about which poet Emily Dickinson wrote.

Donna Ruff (American), 1.15.16, 2016

Donna Ruff (American), 1.15.16, 2016

Hand cut deacidified newspaper

Sheet: 15 3/4 x 23 in.

Purchase

Smith College Museum of Art, SC 2017:36

At first glance this work may appear to be a piece of aged fabric, or perhaps a piece of lace, but glimpses of a headline and other photographic images reveal it for what it actually is: the front page of a newspaper. In this work, Donna Ruff draws on her Jewish upbringing to create a work that juxtaposes the “feminine” delicacy of cut paper against journalistic images of religious war and protest. The Islamic patterning of the cut paper recalls the prohibition against representing figures in both Islamic and Jewish religious art, while the image of women left intact makes us question the way they are represented. What is their place in this drama?

Louise Fishman (American, b. 1939), Untitled, 1972

Drawing, Photograph, and Print: Photostat, charcoal, and pencil on paper, overall: 11 7/8 in x 28 1/4 in.

University Museum of Art, University of Massachusetts Amherst, UM 1973.5 Purchased with funds from Fine Arts Council Grant

Between 1971 and 1972, Louise Fishman produced a series of intimate untitled works fashioned by dyeing canvas in her kitchen sink, cutting them into pieces, and then sewing them back together in a grid-like arrangement with thread. This drawing is contemporary with that series, where Fishman’s grid format controls and repeats her aggressive mark-making. The grid is a common device in modern painting, inspired directly in this case by the work of minimalist artist Agnes Martin. Here, the grid evokes traditions of quilt-making, a medium Fishman related to women’s experience. Her forcefully drawn marks conjure techniques used by male painters in the Abstract Expressionist movement. Fishman developed Feminist confrontations most famously in her “Angry Women” paintings of 1973, where she scrawled the names of fellow female artists on canvases in an expressionist manner. Here, she approaches her drawing as a form of quilt-making, emphasizing the gender politics of her use of materials.

Louise Fishman (American, b. 1939), Untitled, 1972

Drawing: photostat, charcoal, and pencil on paper

overall: 22 1/16 x 30 1/4 in.

University Museum of Art, University of Massachusetts Amherst, UM 1973.6 Purchased with funds from Fine Arts Council Grant

Dating to the same year as the Untitled drawing, Fishman applies similar techniques of expressive marks in a grid-like pattern that recalls traditions of quilt-making. However here, Fishman develops forceful marks in fluid colors. These saturated hues call to mind the vivid colors in her “Angry Women” paintings of 1973 in which she boldly writes the names of her female colleagues, using gestural abstraction to confront a male-dominated artistic discourse of painting. The use of bright color recalls Abstract Expressionism, but the small scale drawing competes, provokes, and politicizes materials to suggest feminist perspectives.

Sondra Freckelton, (American, 1936- )

Sondra Freckelton, (American, 1936- )

Openwork, 1986

Screenprint (17 Colors) on BFK Rives white paper

Sheet: 21 5/8 x 28 in.

Mount Holyoke College Art Museum, MH 1987.2

Gift of the Mount Holyoke College Printmaking Workshop

Sondra Freckelton began her career creating sculptures in plastic and wood. In the 1970s, during the second wave of feminism, she turned to realistic still lifes in watercolor and screen printing techniques. Historically, the still life tradition has a lower value in the hierarchy of painting genres. It was often associated with amateur artists, or women in the academy because they were unable to study the human body like their male counterparts. By taking on the still life subject, Freckelton confronts the old hierarchy of genres. Her flowers, vegetables, and handmade objects associated with feminine activities such as quilting, gardening, or embroidery present feminist revisions of the perceived divide between art and craft.

Gloria Frankenthaler Ross (American, 1923-1998)

Point Lookout, 1966, after Helen Frankenthaler, American (1928-2011) Hooked (tufted) wool on canvas, edition 4/5

Overall: 72 x 30 in.

Gift of the Storm King Art Center

Mount Holyoke College Art Museum, MH 1986.10.2

Point Lookout is a copy of the original painting by the artist’s sister, Helen Frankenthaler, a Color Field artist. Helen Frankenthaler developed a unique visual vocabulary and stain painting technique. She created Point Lookout by thinning the oil paint until she could apply it like a watercolor and allowing it to stain the canvas. As color field artists experimented with painting techniques, Gloria Frankenthaler experimented with the reproduction of an expressive painting by using hooked wool on canvas. Ross referred to this technique as “translating paint into wool”. The wool strip represents the artist’s line, tamed to draw the desired form and provide it with a new texture.

Gloria Frankenthaler Ross (American, 1923-1998)

Spanish Elegy #78, 1965, after Robert Motherwell, American (1915-1991) Hooked (tufted) wool tapestry

Overall: 72 x 132 in.

Gift of Mrs. Marjorie Iseman

Mount Holyoke College Art Museum, MH 1978.6

The original painting series, by Robert Motherwell, “Elegies to the Spanish Republic” was inspired by the Spanish Civil War in 1936. The abstract forms venerate the civil war victims and human suffering. Here, Gloria Frankenthaler Ross “redrew” the male artist’s painting using a technique associated with female experience. The hooked tapestry technique has been in use for hundreds of years mostly as a humble, feminine activity. Rugs were crafted using all kinds of available material. Ross’s tapestry presents painting in a new light, calling attention to the hooked wool technique as a method of creative translation.

Beth Van Hoesen (American, 1926-2010)

Sewing Basket and Pin Cushion, 1968

Ink on medium weight, very smooth, white paper

Sheet: 9 13/16 x 8 in.

Gift of the E. Mark Adams and Beth Van Hoesen Adams Trust Smith College Museum of Art, SC 2012:5-2

Beth Van Hoesen was an internationally renowned American printmaker, who made extensive use of drawing as a preparatory medium. Drawing allowed her to explore the connections between femininity, delicacy, and women’s work. She turned towards the microcosm of everyday life, including flowers and fruits, landscapes with animals, and domestic scenes as seen here. The intricacy of the lines captures the delicacy of threads, and suggests the act of sewing. With meticulous observation and a steady line, Van Hoesen captures the repetition and quietness of domestic tasks, giving new importance to everyday experience.

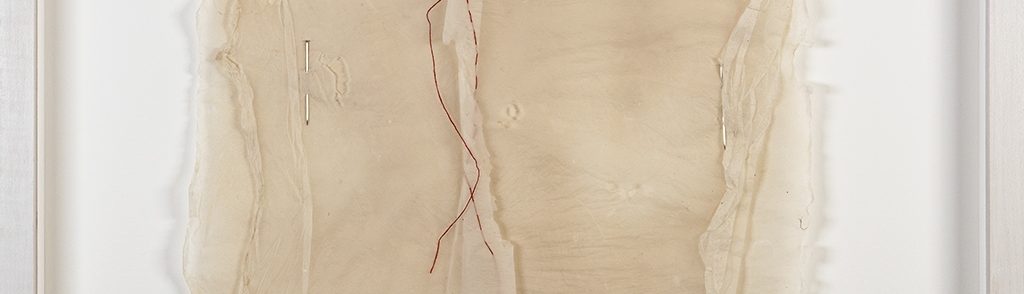

Olivia Bernard (American, b. 1945)

Red Stitch, 2010

Abaca paper, thread, pins Overall: 14 x 11 in. Museum Purchase

University Museum of Art, University of Massachusetts Amherst, UM 2017.6

Elegant and peaceful, sculptural yet intangible, connected yet unsettling – Red Stitch comes from the hands of local Massachusetts artist, Olivia Bernard. Part of her series of handmade paper drawings, the layered paper features a partly stitched red thread that gently hangs down, becoming the drawn line. Bernard believes that “drawing is a search, a barometer of my unconscious”. The handmade paper and thread resonate with feminine experience, while the disappearance and reappearance of the stitches create an underlying tension. The use of bold red in such a delicate material confronts viewers with new questions about it’s significance: does it speak to vulnerability, subtlety, connectivity, or an unyielding perseverance?

Harmony Hammond (American, b. 1944)

Indian Basket, 1972

Charcoal, graphite, tempera on paper

overall: 25 x 37 1/4 in

Purchased with funds from Fine Arts Council Grant

University Museum of Art, University of Massachusetts Amherst, UM 1973.4

Indian Basket, by pioneering lesbian feminist arts Harmony Hammond, depicts the bird’s eye view of a basket weave in progress. While the majority of Hammond’s works focus on the meaning of materials, her works from the early 1970’s emphasize the deep connection between women and material, specifically weaving. In Indian Basket, Hammond layers tempera so thickly on the canvas that the work becomes almost sculptural. This approach to weaving with paint recalls the history of women and weaving, but also stakes a claim for female experience in abstract painting.

Mary Ijichi (American, b. 1952)

String Drawing #2, 2002

Acrylic and string on Mylar, acrylic and metal hanger Overall: 148 x 40 in.

Gift of Werner H. and Sarah‑Ann Kramarsky

University Museum of Art, University of Massachusetts Amherst, UM 2003.1

String Drawing #2 reflects an experimentation with dots and lines as well as the artist’s reinterpretation of her Japanese heritage. Ijichi was inspired by the ability of contemporary communication to hide the truth. The horizontal lines and asymmetrically places knots suggest an illegible script. The subtle variation of the pattern provides a tranquil, meditative effect. The resemblance of the artwork to a hanging textile recalls the tradition of women’s weaving in Japanese culture. In the Japanese Shinto religion, Amaterasu is the goddess of weaving.

Faith Ringgold (American, b. 1930), And Women?, 2009

Serigraph; ink on Rives BFK White. Sheet: 15 x 22 1/2 in.

Gift of the Mount Holyoke College Printmaking Workshop

Mount Holyoke College Art Museum, MH 2010.14

As one of the six prints in the portfolio “Declaration of Freedom and Independence,” the feminist activist and artist Faith Ringgold uncovers the inadequacy in the United States’ founding document, and it’s history of social injustice and inequality. Appearing side-by-side are the silhouettes of two important historical women each juxtaposed with historical texts about women’s rights. The image of Abigail Adams on the left is overwritten with her earnest letter to her husband to “remember the ladies”, and the image of Sojourner Truth on the right features the text of her speech “Ain’t I a Woman?” famously delivered in 1851 at the Women’s Right Convention in Akron, Ohio. Ringgold challenges us to consider the changing status of different groups of women in the U.S. Her work also calls attention to the changing perception of calligraphy, from a neutral or masculine endeavor to a modern feminine art form.