by Melanie A. Griffith

Walt Disney Studios, American (20th century), Scene featuring Timothy Q. Mouse from ‘Dumbo,’ ca. 1941. Tempera on celluloid. Mead Art Museum, Amherst College, AC 1969.24. Gift of Dr. Jack W. C. Hagstrom (Class of 1955)

There are many types of art in this world, ranging from traditional paintings, prints, sculptures, and ceramics to the more radical concepts of the abstract. Within the walls of a museum, these items are collected, stored, and exhibited, so that people can come and stand in awe of their skill and beauty. However, among the priceless vases and Van Gogh paintings, one might come across something they would not have expected to be displayed in a gallery: a thin sheet of clear celluloid – a Disney animation cel. The process of animation is considered more of an art today than ever before, especially in the more digital realm; but even then it is often set aside in its own category, hidden almost in shame and considered an outcast in the art world. Digital art and media has gained a foothold in museums through exhibitions and installation-based works. The process of hand drawn animation, however, is now rarely shown or appreciated. While digital art has evolved considerably, and been accepted as the better and more advanced aspect of animation, the importance of tradition is slowly forgotten.

Despite popular belief, cel animation is art. It takes just as much skill, artistic style, and work as any other art; uses the same mediums, tools, and basic principles as the milestone artists of history; and utilizes other skills found in other areas of art, including film, design, and repetition.

To begin, cel animation takes a lot of skill, a firm hold on one’s own style and the styles of others, and a lot of honest hard work. Skills are things that take practice, things that take hard work and persistence on the part of those who wish to master them. This can be said of any art form, and animation is no different. It is art because just as much work, skill, and practice is put into it as any other art form. This can be seen most notably in the “classic” years of Disney films, during the age of cel animation, before the use of computers.[1]

Individuals who go to college for animation start their education where all artists do: in a beginner drawing class. The basics – working with lead, ink, charcoal, and other common mediums – help an animator learn how to draw. While cartooning is a far more stylized category than traditional or classical drawing, it still requires the know-how to convey objects and persons. A cartoon cat might not look real or authentic compared to an actual cat, but it still has to be recognizable as a cat.

Another skill that must be mastered is the ability to convey emotion in a character, either through movement or expression. This is no small feat. Expression and movement can define the personality of a character – their thoughts and emotions – so that the viewers become attached to them on a deeper level; so that they feel what the character is feeling, or feel for the character. This, again, takes a lot of practice, and keen observation.

A good sense of timing and pacing is also important. Comedy, realistic movement, and speech in animation all take a cue from the animator’s hold on timing. Things that are meant to be funny will be considerably less so if the timing is off. Likewise, if the timing is perfected, it can lead something common to seem hilarious. Movement also relies on timing, so that things line up realistically, including with speech. Pacing sets the speed that all of these aspects create as a whole. If the pacing for a story or animation is too fast, it can appear ‘cheesy’ or hurried. Whereas taking the appropriate time to work through a scene, giving the audience time to absorb what they are seeing, will give the animation a far higher quality.

Creating and maintaining a certain style also takes a fair amount of skill and practice. Obviously, if a film is going to be made, all the animators have to be on the same page when it comes to how the characters and backgrounds look, move, and act. Otherwise the film will appear disjointed and un-united. Unless, of course, that is the goal.

A firm understanding of one’s own style and limitations, as well as a willingness to push past those limitations, is a large part of animation. There are many, many styles, each unique to any one person. While this is important, a knowledge of how to imitate other peoples’ styles is also crucial. During early production and development of an animated film, concept artists drew their own ideas and versions of what the characters and overall style of the film should look like. When designs were chosen, the film development progressed with that style, and everyone had to conform to it. Lilo and Stitch is a perfect example of this.[2] With a style that stands out as different from most other Disney films, the style was determined by the art of one artist, who made work for early development for the film. When the other artists and higher ups of the department saw their work, they instantly fell in love with it, and the decision was made to make the whole film in that style.

Animation is hard work, plain and simple. It takes an immense amount of practice, as well as patience. Drawing a single character or item over and over again takes a good eye, and a willingness to draw repetitively. Preliminary sketches, made before any work on the actual animation of a film even begins, can mass in the thousands. Sheets depicting the characters running, jumping, sitting, or interacting in a variety of ways enables the artists to draw them from every angle, and in any action. Once that is accomplished, then they can move on to drawing the film itself, with the illusion of life requiring a total count of 24 frames per second.

Just as it is for the masters of drawing and painting, such as Leonardo de Vinci, sketching is an essential part of the animation process. The ability to draw things out quickly, as a means of study or reflection, is extremely valuable. Animation companies often hired models to come in and act out a scene for their artists, to give the animators a better understanding of what to draw. Models brought in included women, men, children, and sometimes even animals. Study of form and figure was important. Without it, characters would appear malformed, unless that was the animator’s intention. An understanding of how to draw the human figure, as well as an understanding of the anatomy, was a large factor to be considered. Otherwise characters would not move in a believable manner, even if they were meant to be cartoony in nature. Knowing how to convey weight, gravity, timing, motion, and exaggeration would all have been important – some to add realism, such as gravity and weight, and others to stretch the laws of physics to match a more cartoon-based reality, like exaggeration.

Figure 2. Horse sketches by Leonardo de Vinci – Just like animators, the need to practice and draw subjects from various angles and poses is extremely important.

Finally, traditional animation takes drawing to a whole new level, relying on repetition and patience as a means of bringing something static to life. The process involves many different art forms, including drawing, painting, and registration, and takes a considerable amount of time and work.

The first step to making an animated film during the golden age of Disney was, naturally, the story; but once the main idea was attained the artists would begin their work. Concept artists created thousands, even millions of drawings, some of which would be used for storyboards, to be read through and then discarded as the story changed or progressed. Character styles and designs would be brain-stormed, the artists each coming up with their own ideas and bringing them together to discuss. When an appealing style and design was found, work would then continue, practice being important, since the figures would be drawn again and again throughout the course of the movie.

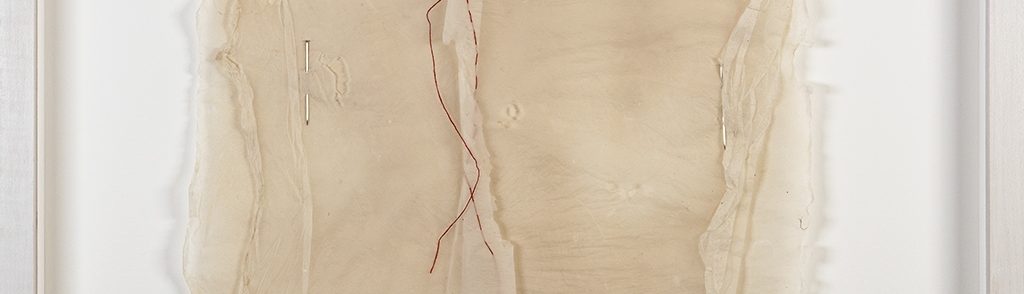

Once the characters and story were solid, progress on the actual film itself would start. Again, the source came right from the pencils of the artists. Lead to paper, they would sketch out and then refine every frame to be used in the motion picture, working out the movement, expressions, and how the characters’ mouths would move, so that they matched up with the voice actors’ lines. As Disney gained a far more extensive list of movies, some footage was reused to save money and time. For example, drawings used for the dalmatian puppies in 101 Dalmations[3] were later used for the wolf cubs in the beginning of The Jungle Book.[4] Once the pencil drawings were satisfactory, they were brought to the xerox department. Here, the drawings would be transferred to a cel. A cel is a thin sheet of celluloid that the drawings could be imposed onto, so that the characters stood out, but their surroundings remained transparent, enabling them to be layered and creating an illusion of depth as well as make it possible to animate some layers while leaving others static. This layering is evident in the Mead drawing from Dumbo. It is accomplished through a process that takes the image and makes a more permanent copy on a plate. This plate is used as a template, or print, to then move the image to an animation cel. However, even then the cel and its drawing were not permanent until after they were treated with a chemical vapor.[5]

These cels were then critically checked with the original drawing, to make sure that nothing was out of alignment or that any mistakes had shown up during the xeroxing process. Registration – the small marks that ensure each frame is matched exactly – was also checked for any errors.[6]

With the drawing finally on a cel, the frame was sent to the inking and painting department, where a team of artists would ink and color them. Certain stations, or select individuals, would be in charge of a particular character or even a particular color. It was very important that the colors be exactly the same in each and every frame. While the difference would have been minimal to any casual eye, when played in quick succession at twenty-four frames per second, the changing tones would have been very visible. The likelihood of the colors changing in hue at all during a scene was minimized by mixing enough ink of each color so that they would not run out, since it was very hard to get the exactly same tint every time. The ink was applied in a “pooling” manner, rather than strokes, so that no lines were visible.[7]

Cels that were completed were tested, and then put under lighting and camera to be shot. Sometimes there would be multiple cels, one on top of another; the still background on the bottom, followed by any number of cels that would be animated on top, interacting with one another. All of the individual frames were shot, strung together as film and then finally finished, ready for the theater. This process of creating animation in an assembly line sped up the process as a whole, leading to more cartoons and films being possible within a shorter time frame. Even then, most fully animated films were four years at the least in the making, sometimes more. While Disney is most certainly the most renowned in the animation industry, the techniques discussed so far were not his own. Such innovative men as Winsor McCay and J. R. Bray brought the popularity of animation to light as early as the 1910s.[8]

While the technological advancements in digital animation are amazing, and reach new heights with every passing year, there is something to be said for the traditional aspects of animation. Drawing things by hand breathes more life into a character, as well as more of a stamp of an individual artist’s style.

Today, it has become harder and harder to determine an aesthetic difference between one animation company’s movies and another. People see movies created by Dreamworks or Disney, and just assume, because of how it looks, that it was made by Pixar. This is because we have begun to associate the computer-generated imaging style that larger animation companies have adopted with the studio that first made it popular. The use of similar software and programs makes the processes in digital animation virtually the same, with less room for style to play any part in it, unless strictly addressed and pursued by the company and its animators.

There is a reason why Disney uses the phrase ‘magic’ in all of their marketing. Back in the days before Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs[9], animation was used to make very short features, usually in black and white that typically depicted a small handful of generic characters that didn’t speak, or spoke very little, and proceeded to abuse each other to a musical score and a series of sound effects. Steamboat Willie is a perfect example, with Mickey practically beating animals to a musical score.[10] Cartoons were made for the strict purpose of showing off the miracle that was animation, the illusion of movement. Characters swung their arms, turned around, jumped about – all so that the audience could enjoy the idea that something drawn by hand could be made to look like it was moving – but that was it. Ideas of evoking individual personalities and emotions from the characters, other than the comical facial expressions more typical of silent pictures, were not even considered. That is, of course, until Walt Disney claimed that animation could be taken to a level rivaling, or even equaling, that of live films, with the characters becoming their own persons and interacting with complicated plots. He firmly believed that people would be willing to sit and watch a film that was entirely animated from start to finish, and that the technology and know-how was available to pull it off.

Figure 4. Willie Whopper cartoon – Black and white cartoons of this time usually depicted simple characters abusing one another to sound effects and a musical score.

He was thought a fool for these visions, the idea referred to as “Walt’s Folly,” but when Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs made it to the screen, that all changed. Suddenly there were characters with fully thought out personalities, in brilliant color, that interacted through dialogue and plot, rather than simply bopping each other over the head. People were more than willing to sit through 83 minutes of animation, proving that Disney had been right in his assumptions and beliefs. Disney’s studio did not waste any time producing another film, followed by another, and another. The rest, of course, is history.

Hand-drawn animation puts more heart and soul into film and its characters than digital media. In CGI films, the characters and their surroundings are built within a computer software program. They are designed and created with built-in restrictions in place, so that, for example, a character’s mouth can only open so wide, or their leg can only lift so high. While these aspects tend to make a character more realistic, and cut down on an animator’s work by a good deal during the actual animating process, they also set limits to how much movements can be exaggerated. Exaggeration is a very important part of animation, indeed one of its founding principles. Restrictions of facial movement take away from the variety of expressions a character can make, as well as the movements that might have been used to make their motion more comical or smooth to the viewer’s eye. The lines that create the emotional responses of a character are very important, not only visually, but also in how they evoke emotion in the viewers watching the film. This is more important than anything else – even color. Color is secondary since it is not needed to tell a story, but reactions and emotions are. Rules of realism also start to apply more heavily when using computers to animate, making the characters so life-like that they appear less and less animated, and more and more real, eliminating the artist style and hand completely.

In conclusion, animation, particularly hand-drawn/cel animation, is art because of the skill it takes, as well as its conscious and innovative style. It should be admired as art because it uses the same basic principles of drawing found in any other art form, plus others related to the complex medium of film. It not only depicts something that exists, like the artists of old did, but is able to bring life to something that was previously static. While computer animation is indeed impressive and unique in its own way, it can never recreate the individual style and energy that traditional animation can produce. That is why cel animation should be shown among the works of other visual artists in museums. These unsung heroes worked hard, drawing on their skill, patience, and creativity to bring enjoyment to thousands.

[1] Amy M. Davis, “Disney Films 1937–1967: The “Classic” Years,” in Good Girls and Wicked Witches: Changing Representations of Women in Disney’s Feature Animation, 1937-2001 (Indiana University Press, 2011), 83-136.

[2] Walt Disney Pictures, Lilo & Stitch ; Lilo & Stitch 2. Stitch Has a Glitch (Burbank, CA: Walt Disney Home Entertainment, Distributed by Buena Vista, 2013).

[3] Walt Disney Pictures (produced by Walt Disney; story by Bill Peet; directed by Clyde Geronimi, Hamilton S. Luske, Wolfgang Reitherman; directing animator, Marc Davis, et al.), 101 Dalmatians (Burbank, CA: Walt Disney Home Entertainment, Distributed by Buena Vista, 2008).

[4] Jackie Hicken, “50 Things You Might Not Know About Your Favorite Disney Films 1955-1986 Edition,” Deseret News U.S. & World, 10 June 2014.

[5] InklingStudio, “Inking & Painting Cel Animation,” Online video clip, Youtube, 31 July 2014.

[6] InklingStudio, “Inking & Painting Cel Animation.”

[7] InklingStudio, “Inking & Painting Cel Animation.”

[8] David Callahan, “Cel Animation: Mass Production and Marginalization in the Animated Film Industry,” Film History 2, no. 3 (1988): 223-28.

[9] Walt Disney, David Hand, Adriana Caselotti, Harry Stockwell, Lucille La Verne, Moroni Olsen, Ted Sears, et al. Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (Burbank, CA: Walt Disney Enterprises, 2001).

[10] Esther Leslie, “It’s Mickey Mouse,” in Animation: Art and Industry, ed. Maureen Furniss (Indiana University Press, 2012), 21-26.

[11] Disney, et al., Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs.