By Khai Vuong

Representations of the female nude in the European artistic tradition were typically made by male artists who put women on display for a presumed male viewer. The female nude was transformed into an erotic, yet passive, figure by the artist to flatter the male gaze throughout history. Nude drawings have remained a glimpse into a particular society’s standard of beauty as well as the artistic training common at the time. Egon Schiele’s Girl (Mädchen), 1918, and Jean Cocteau’s Head of a Young Man, 1920, both feature a sexualized figure relating to the artists’ sexual identity, with distinct implications for the position of the viewer. As the two artists diverge from traditional views of beauty in these suggestive drawings, they both objectify their subjects in different ways. Schiele explicitly and abjectly presents a female nude, drawing her in an erotic, and contorted manner particularly noticeable when compared to traditional female nude drawings. Cocteau presents a young man through a queer lens, breaking with the standard depiction of men in modern art but returning to classical tropes of homoeroticism. Each in their own way, the two artworks diverge from conventional beauty standards and take sexualized expression to a personalized level.

Jean Cocteau (1889–1963) was a renowned French writer, designer, playwright, artist, and filmmaker. His work is thought to be elegant, precise, and easily recognizable.1 From 1900-1904, Cocteau attended school at Lycée Condorcet, where he had his first affair with another male student. His drawings are highly self-indulgent and illustrate his fantasies, often related to his sexuality.

Egon Schiele (1890–1918) was born at Tulln an der Donau, Austro-Hungarian Empire, and died in Vienna at only 28 years old in the international flu epidemic of 1918. He studied at Kunstgewerbeschule in Vienna and by the insistence of many faculty members, after a year there he transferred to Akademie der Bildenden Künste. The Austrian Expressionist is noted for his nude drawings that make the body into “the vehicle of expression.”2 In particular, he captures the nude model’s pose as if it were in mid-motion, making the body look twisted or contorted. His work “break[s] free from the aesthetic of the Secessionists [as] a turning point to quest for expressive pictorial truth in the representation of human beings, nature, and landscape.”3 His drawings are not used as a means for the eye’s pleasure, but rather to defy the current standard of beauty at the time.

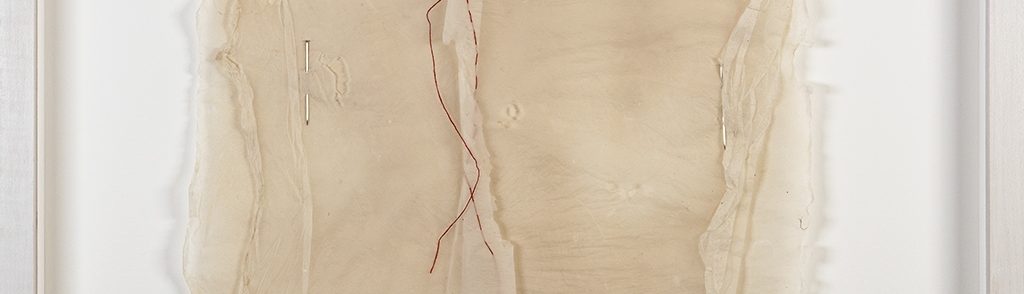

Egon Schiele, (Austrian, 1890-1918), Girl (Mädchen) from ‘The Graphic Work of Egon Schiele (Das Graphische Werk von Egon Schiele)’, 1918, published 1922. Lithograph on wove rag paper. 15 5/8 in x 21 in. Mead Art Museum, Amherst College, AC 2016.13

Egon Schiele’s drawing Mädchen presents to a young girl in an eerie, unnatural pose, perhaps purposefully depicting the figure as lifeless and doll-like. The figure’s body is used as a vehicle of expression where the stylized body language develops the overall tone of work. Upon close examination, the female bodily form is outlined through line, accentuating the bones and awkward contours. Traditional female nudes tend to have fuller bodies; here; the unsteady lines that form her ribs suggest emaciation. With further investigation, her arms, legs, knees, and waist have the same quality of line. Along with the light shading, the contour gives the figure a malnourished and deformed appearance. The majority of color is the black shading in the figure’s hair that lies lightly around her shoulders, back, and the side of her face. The black shading surrounds the girl’s face, drawing attention to her facial expression where she looks astray, suggesting feelings of withdrawal, grief, or loss. The absent and withdrawn expression on her face suggests that her mind has wandered off, creating an impasse in communication with the viewer. As Albrecht and Szeemann describe, the face is “frozen into a facial expression, an attitude and bizarre gesture, which symbolizes the paralysis of communication.”4 The distorted proportions and qualities of line that make the figure seem distant and mysterious express both the subjectivity and the individuality of the artist. She no longer becomes merely the subject of the male gaze, but reveals an unorthodox form of beauty and an emotional vulnerability that suggests her own inner life.

The explicit sexuality of this drawing reflects Schiele’s early development as an artist, when his work was greatly influenced by Auguste Rodin. As Patrick writes of the influence of Rodin’s work, “without that contribution, Schiele would have been a different artist.”5 As Rodin made contour drawings of live models, he would draw the model as they moved without taking his eyes off of them. According to Patrick, this would later become known as instantaneous drawing. Rodin notes that his “object is to test to what extent [his] hands already feel what [his] eyes see.”6 Rodin’s drawings “both encouraged and showed the way by which Egon Schiele could express his sexuality in a individual style.”7 The influence Rodin had on Schiele allowed Schiele to find his own artistic style. Rodin showed Schiele how to replace traditional academic drawing with a more direct use of his eyes in order to confront nature and resist academic tropes of beauty. Schiele’s unique style becomes apparent in his drawings of the nude female as he “uniquely shaped mass and volume as a reflection of their individuality.”8 The woman’s body is highlighted through the contours of her bones, suggesting that Schiele is recording the figure’s individuality. The lines that accentuate the bones become Schiele’s recognizable style, as seen in many of his works. Schiele’s line records an intense examination of the, rendering “the model as if the point of the drawing instrument was actually passing over the contours – like a finger probing the flesh.” Rodin also inspired Schiele in how to arouse, sustain, and convey his feeling for women, as well as to possess the model in an intimate, artistic way. Without the guidance of Rodin, Schiele may have still drawn nude figures but may not have developed the same individualized style or freedom from his “self-consciousness about style and technique, and to his own eroticism” by drawing nudes that did not conform to the classical notions of figural beauty.

Schiele’s models were not restricted to their pose but instead liberated, able to “not only move by walking and dancing but assume positions that were not part of the art-inspired repertory of models.”9 Schiele “emphasiz[es] how well the figure holds its place within the field of drawing rather than responding to the laws of gravity.” His work moves beyond traditional academic styles of drawing to find a new way to achieve the figure’s compositional balance. The figure becomes a cipher of the artist’s radical vision as well as a radical new understanding of female sexuality. As Kallir writes, Schiele “ratified the independent power of female sexuality. There was a controlling male narrative holding the women back. The female ‘other’ came into her, and she could, with her unnatural coloration, contorted posturing, and impenetrable stare, be scary.”10

Schiele’s models were his age or younger, and sometimes even children. It is important to note that Schiele considered it an illusion that that one could depict young girls as models and not see them sexually. Young girls were thought to suppress homoerotic urges as their undeveloped bodies were physically less threatening to some men than grown women. Schiele remarks, “Have adults forgotten how corrupted, that is, incited and aroused by the sex impulse, they themselves were as children? Have they forgotten how frightful passion burned and tortured them when they were still children? I have not forgotten, for I suffered terribly from it”11 Schiele’s nude drawings do not focus on child sexuality itself, but rather the ambiguous interval of adolescence.

For his choice of younger models and sexual drawings, Schiele was charged and sentenced to prison in 1912. The incident happened when the 14-year-old Tatijana Georgette Anna von Mossig ran away from home and sought refuge in Schiele’s studio. She returned to her family several days later and her father went to the police. Authorities raided Schiele’s studio, “from which they came away with a bounty of erotica. Authorities who found his art considered them to be pornographic. On April 13, 1912, Schiele was imprisoned [….] He was formally charged with kidnapping, statutory rape, and offense against public morality.”12 An Austrian judge, Franz Wishin, hypothesizes that when Schiele directed his child models, he may have “touched them in a manner that could be misinterpreted as sexual abuse.” Schiele’s approach to nude drawing attracted negative attention as it was seen as a taboo, but his approach to nude drawing avoids the standard gendere biases as well as in that he depicts his female models in a way that challenges the male gaze. He resists the standard gender representations of his time by presenting his figure as an unhealthy or decadent nude subject using atypical poses, challenging the male gaze that viewed the nude female figure as a comforting object of beauty and desire.

Jean Cocteau (French, 1889 – 1963), Head of a Young Man, 1927, dark grey ink on thin cream wove paper, 10 1/2 x 8 3/16 in. Smith College Museum of Art, SC 1972:50-15

Jean Cocteau’s Head of a Young Man is a drawing from two decades later, stylistically inspired by the radically simple contours of Henri Matisse. Cocteau uses minimal lines to present a young man posed and looking sideways into the distance. Drapery hangs around his shoulders, covering part of his chest while revealing what appears to be the right nipple, placed high on the body to suggest a semi-reclining pose. The figure poses intentionally, with his hand on the back of his hair and his head turned sideways. The boy’s evident youth suggests that he is a modernized version of a classical Greek hero, an idea that relates to the curls of his hair as well as his drapery (though a devilish horn is equally deliberately drawn into the contour of his hair). At first glance, Cocteau’s drawing appears to be nothing simpler than an image of a young boy; however scholars note that Cocteau “took the time to illustrate his fantasies” and “the truth of these pictures lies beyond what we can see in them.”13 The drawing recalls Cocteau’s many more explicit drawings illustrating gay sexuality. The young man in the drawing could be presumed to represent an object of desire, making this an image constructed for a queer male gaze. Male figures more typically appear well defined, confident, and shown in stronger or more dominant poses. In Cocteau’s drawing, by contrast, the young man’s more passive, and thus feminized, pose and appearance suggest Cocteau’s homoerotic interest and vision. The boy’s hand in his hair and his turned head suggest that he is looking into the distance. The gesture evokes an alluring dream of a figure depicted by Cocteau as seductive and tempting.

The two artists pose their figures to send a message of sexual expression. However, their works are not pornographic or to be used as a means of unmitigated pleasure or arousal for the viewers’ eyes, as in traditional male and female nudes. Schiele’s nude drawings evoke fear, darkness, or revulsion as much as erotic arousal. Critics state that “if the litmus test of pornography is to excite the viewer, then Schiele is no pornographer.” Schiele ignores conventional gender boundaries and his nudes provide “an affirmation of his own inchoate feelings.”14 His female figures enter the viewer’s space by posing in nontraditional ways, and many of his figures during 1917-18 are distinctly shown to “own their sexuality.”15 The nude women in his drawings seem to take back some control of their seductive bodies and express themselves. Cocteau’s drawings suggest a playful element of his own fantasy of men as an object of desire. Cocteau depicts a queer perspective, where figure turned sideways appears to turn away from classical depictions, and read as an object of desire for multiple subject positions, straight or gay.

Historically in European art, men were usually depicted in heroic terms as a soldier, savior, or lord. If the women were the subject, especially of a nude drawing, the female would be depicted as a passive object displayed for the enjoyment of a primarily male audience. Both Cocteau and Schiele deliver their drawings with no intention of following the traditional depictions of constructed gender roles, whether masculine or feminine, but create instead a new meaning of masculine or feminine sexuality according to each artists’ own perspective. In Schiele’s case, the nude drawing diverges from classical notions of beauty. The radically unconventional female figure in Schiele’s drawing returns the viewers’ gaze. His figures attack the standard of nude drawings of women by liberating the unconventional aspects of the model’s feminine sexuality, rather than merely pleasing the gaze of a male viewer. Cocteau’s depiction of a young boy does not represent the male as a masculine image of power such as a king or savior, but gives the figure qualities of a modernized Greek hero. Greek heroes, while they often do represent masculine qualities, in Cocteau’s drawings stand for the beauty of male youth as a homoerotic ideal: they “represented the physical form which so he wanted to possess himself.”16 The youth of the boy contributes to his sexualization as an object for a queer gaze, allowing the viewer, too, to enter the fantasy of temptation and seduction the figure portrays.

- Anne Guedras, et al., Jean Cocteau: Erotic Drawings (Evergreen, 1999), 2 ↩

- Klaus Albrecht Schröder and Harald Szeemann, Egon Schiele and His Contemporaries: Austrian Painting and Drawing from 1900 to 1930 from the Leopold Collection, Vienna (Prestel, 1989), 35 ↩

- Albrecht and Szeemann, “Egon Schiele and His Contemporaries,” 16 ↩

- Albrecht and Szeemann, “Egon Schiele and His Contemporaries,” 31 ↩

- Patrick Werkner, Egon Schiele: Art, Sexuality, and Viennese Modernism (The Society for the Promotion of Science and Scholarship, 1994), 7 ↩

- Rodin, quoted in Patrick, Egon Schiele, 10 ↩

- Patrick, Egon Schiele, 11 ↩

- Patrick, Egon Schiele, 13 ↩

- Patrick, Egon Schiele, 16 ↩

- Kallir, Egon Schiele: Women, 112 ↩

- Schiele, Prison Diary, 1912 ↩

- Jane Kallir, et al. Egon Schiele: Women (Richard Nagy, 2011), 147 ↩

- Guedras, Jean Cocteau: Erotic Drawings, 5 ↩

- Kallir, “Egon Schiele: Women,” 264 ↩

- Kallir, Egon Schiele: Women, 266 ↩

- Guedras, Jean Cocteau: Erotic Drawings, 7 ↩