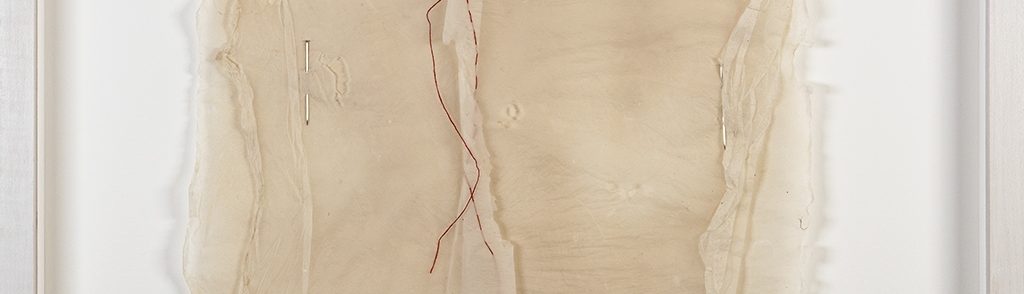

Sheila Hicks (American, active in France, b. 1934) Mystery Object, n.d. Cotton cloth and silk thread, 3 in x 7 in. Mead Art Museum, Amherst College, AC 2016.39

By Ismene Markogiannakis

For centuries, drawing has been associated with two dimensional surfaces, and standard drawing utensils. Artists use drawing to translate their ideas and inspiration on paper, and eventually develop them into a finished work of art. At the same time, drawings can also be used for three dimensional development. Drawing can take sculptural form as artists experiment to develop a vision with their intended material. This practice is evident in the work of renowned textile artist Sheila Hicks. Two works by Hicks, the small sculpture called Mystery Object and the larger finished installation from the exhibition Séance, possess complementary features of drawing. It may seem unconventional to compare sculptures to drawings, yet, fiber as a fine art was equally unconventional until very recently. In relating sculpture to drawing, Hicks’ work has the ability to break down the divide between two and three dimensional art.

Sheila Hicks is an American artist active for the past several decades, who has been called the “Painter in Thread.”1 This inspiration for her long career sparked when she traveled to Latin America after college. There, she was impressed by local craft traditions featuring beautiful and vibrant colors.2 Traditionally in Latin American as well as other cultures, textiles are viewed more as functional than artistic. During these travels, Hicks “was never without a small hand-loom,” in place of a regular sketchbook when practicing this “new found” art.3 Many artists still use pencil and paper to translate ideas visually; however, executing those ideas with the same material as the finished outcome is essential to understand how a material can be manipulated. That is why Hicks uses “small-scale studies to work through ideas she can apply to her larger pieces.”4 For Sheila Hicks, “the small woven forms are an essential means of creative expression” as they “provide a format for mastering approaches to materials and techniques that she then frequently applies to works of differing scales.”5 Hicks was also “one of the first to involve the floor” in her creations as “a total rejection of the traditional tapestry,” rejecting the limitations that prevented women who traditionally wove such tapestries from being seen on an artistic level equal to male artists.6

Textile was a practice done since ancient times, created for survival against the natural elements. For centuries, textiles were also used as a form of storytelling, from ancient Greece to the Middle Ages.7 Even given its past importance, during the 1960’s, as textiles began to be officially introduced as Fine Art, many still disagreed with this designation. At first, fiber was not well accepted within the high art world, and fiber artists usually dismissed as “a woman pursuing womanly activities.”8 Given the discrimination that still exists towards women in the 21st century, it is no surprise that discriminatory perceptions affected women artists in the 19th century and 20th centuries, even as women were finally recognized as official artists. Fabric and textiles were strictly seen as a woman’s material, “because fiber art was associated with the ‘female’ sphere of domesticity and intimacy,” far beneath the male dominated art forms such as painting or metal sculpture; therefore “feminists seized on it to unravel embedded sexual politics.”9 Soon, women would find a way to achieve recognition for textile art within the art world, and men would follow in their footsteps as well, mainstreaming textile art beginning in the 1970s. Critics who did not agree with this form of art would still not give textile the pleasure of being called fine art. Hicks ignored these judgements and retaliated by stating her own “building principles” for fiber as sculpture. She insisted the fiber “be natural and piled up, not artificially draped over armatures.”10 Hicks believes that textiles can be much more than just crafts or accessories to other works of art. They can be sculpture in their own right.

A single stroke of a pencil is like a fingerprint for an artist. Each mark is unique, a signature of the specific artist that helps identify and categorize their work. Standard drawing is still a practice that every artist uses to develop their skills and their own individual styles.11 Artists who prefer to work in a different medium often still start with a simple pencil and paper, but they also experiment with their selected materials before proceeding towards their final creation. The artist can then familiarize themselves with how the material acts and reacts with its surroundings. Drawing itself can also constitute a finished work of art, but drawing in the sense of practice is better described as a “sketch.” The sketch can be done in any material. Still, the difference between drawing and final works is a fine line, often extremely subtle to distinguish. Hicks states that her work breaks with the grid format that usually delineates a finished textile work, stating that, “the grid is a concept, a way of thinking but is rarely applicable to all materials.”12 In her work the grid is broken and welcomed into the physical world. Line, too, is broken and reimagined into sculpture, taking on new dimensions and meanings.

Hicks’ sculptural drawing Mystery Object, in the Mead Art Museum, is small and rustic looking. The work’s scale and unrefined appearance suggest that she may have produced it as an experimental artwork or sculptural sketch. It features exposed stuffing of beige cotton cloth, tightly wrapped by pink silk thread. Scraps of paper are layered over the cloth stuffing. There is a single, contrasting sage green thread hidden among the pink ones. Larger versions of this palm sized cushion can be found in Hicks’ work, but in forms consisting entirely of threads in more colorful hues. By using scrap materials and working on a small scale, Hicks is able to experiment with an idea without using valuable materials.

What the sculpture actually represents is an enigma. Due to the materials used and the miniature size, it resembles a pin cushion. The pink string so tightly wrapped around the neutral colored fabric suggest a relation to the human body, such as a heart enclosed with veins and arteries. The choice of a feminine color demonstrates Hicks’ interest in women’s strength and empowerment. Or perhaps, because of its small size, it represents a personal keepsake. The name Mystery Object suggests an unknown object kept secret within the wrapper. Although possibly a sketch, its evocative and poetic qualities allow viewers to draw their own conclusions as to what it represents.

The line work in this object is prominent. The pink string stands out from the surface as the main focus of the sculpture, perhaps wrapped out of one single overlapping strand. Many of Hicks’ works develop out of a single strand of yarn.13 The single, uncut pink thread, although thin, could suggest feminine strength or even the durability of feminism’s claim for equal rights. The silk material that constitutes the thread could also symbolize femininity or royal elegance. Its luxurious color and sheen contrasts with the rustic quality of the brown paper and cloth. Hicks plays on the different associations of contrasting materials, the two dimensional and three dimensional. Her sculpture gives line a purpose greater than just the delineation of a mark.

In contrast to her small sculpture, Hicks is known for her massive installations made with impressive amounts of material. In her exhibition called Séance, Hicks amazed viewers with waterfalls of thread draping downwards from the high ceiling into piles onto the floor. In order to execute such large creations, advanced planning and calculation was necessary. A “seance” is the practice of communicating with with spirits from another world. Hicks represents this term rather ingeniously, by incorporating a variety of vibrant and powerful colors arranged in a manner that suggests a connection to an otherworldly realm. The verticality of the piece suggests the connection between heaven and earth, while the material intensity and inviting softness of the colored thread evokes a quality of heaven on earth. The sculpture can also be viewed in reverse: the material world could be dematerializing into the next realm, as all things eventually come to an end, and the cycle begins again. Art is a connection between artist and audience, similar to a seance: the artist is often absent when the work is put on view, but symbolically present in the work. Hicks uses her three-dimensional colored lines to draw connections between artist and viewer in the best way possible.

Although exhibited as a finished work of textile sculpture, the Séance installation also shares many aspects of drawing. In an interview, the artist provides some insight into her material selection: “I want the desire to touch to be very much alive. I think that is important, the wanting: the desire to hold it in your hands, to befriend it, to see if it bites, or if it’s compatible to your existence.”14 The physical intensity of her material creates an invitation to appreciate and interact with Hicks’ work. Just as in her smaller sculpture, Séance is a sculpture composed primarily of three-dimensional line. The long, thick individual strands of thread that are bundled together and suspended from the ceiling provide a sense of monumental presence. Throughout the waterfall of colored thread appear indications of knots and intertwining. In her journal, Hicks writes: “it’s the knots that interest me the most, where one thread becomes attached to another. Joined together, overlapping and twisting actively.”15 While some of the threads might be uncut and continuous, the knots suggest a deeper meaning, such as the cutting and mending of ties between the material and spiritual world, or the constant attempt to maintain contact with those who have passed. The trajectory of line, in sculpture as much as in drawing, is how the artist conveys her message.

All of Hicks’ works share an interest in the organic properties of her materials. Fiber is a naturally malleable material. Instead of working against this, Hicks embraces the nature of the material and allows it to act on its own. Both of these sculptures involve irregular shapes that look foreign, yet welcoming because of the familiar quality of the material. Although the materials in both sculptures are different, they both involve fiber materials that Hicks manipulates, using linear trajectories, to suggest symbolic narratives, whether about feminism, everyday life, or spirituality.

When Hicks began to work in textiles, she wanted to use bright and powerful colors that ranged through the entire spectrum. As seen in both works, color plays a major role in this sculpture just as it commonly does in painting. The artist states that “painters paint, and draw with color. But that’s not enough for me. I want to give it more body, I want to make it stronger.”16 The color relationships that she develops are based on her extensive knowledge of color theory, inspired by her reading and her encounters with local craft traditions during her travels to countries like Mexico and India.17 Her objective is to always let her art speak for itself through material, composition, and color, as evident in both of these sculptures.

Given the major differences between the two works, notably their difference of scale, it may be that Mystery Object is a sketch for a sculpture, whereas Séance is a finished installation. Mystery Object suggests a lack of completion both in its small scale and its use of scrap materials, since Hicks normally uses all fiber material in her work. Just as in painting, the artist can preserve their quality materials for the final projects, and experiment with less important materials in sketches. Color also distinguishes the two artworks. The vibrancy of Mystery Object is much more subtle than the flooding of color in installations like Séance. This is not to underestimate, however, the value of the artist’s smaller creations. Although less monumental, Mystery Object produces a more intimate experience. This intimacy also suggests a connection between artist and viewer, and develops through the humble imperfection of the piece. For some, it may be even more valuable, much like a drawing in a worn sketchbook.

Thread is a physical object with its own form and volume, one that Hicks uses more as a sculpture than as a drawing. While more two-dimensional contemporary tapestries, like Diane Itter’s Southern Borders work of 1982, might suggest drawing more directly given their two-dimensional patterning, Hicks extends the concept of drawing into space and allows viewers to interact with it through bodily experience. Fiber art shares qualities of both sculpture and drawing. While drawings are normally seen as fragile, two-dimensional creations and sculpture more stable and three-dimensional, fiber art may involve either quality or both at the same time. Simple sewing of beautiful patterns can be considered a form of drawing, while lovely rainbow waterfalls from the ceiling can be considered a sculpture. Only by stripping away such predisposed restrictions and criteria can artists continue to explore and create. Sheila Hicks, one of many strong women pioneers of fiber art, broke through the constraints of the male dominated art world and empowered women fiber artists by redefining the labels that were meant to keep them on the outside. By weaving her way in from the margins, she found her own artistic voice.

- Marion Rivolier, “Painting space with threads by Sheila Hicks in the Centre Pompidou” Urban Sketchers, 2018 ↩

- Janelle Porter, Fiber: Sculpture, 1960-present, Prestel, 2014, 202 ↩

- Porter, Fiber: Sculpture, 1960-present, 202 ↩

- Porter, Fiber: Sculpture, 1960-present, 202 ↩

- Bard Graduate Gallery, “Weaving as a Metaphor,” Bard Graduate Gallery ↩

- Porter, Fiber: Sculpture, 1960-present, 17 ↩

- Porter, Fiber: Sculpture, 1960-present, 7 ↩

- Porter, Fiber: Sculpture, 1960-present, 10 ↩

- Porter, Fiber: Sculpture, 1960-present, 19 ↩

- Porter, Fiber: Sculpture, 1960-present, 202 ↩

- Daniel Mendelowitz and Duane A. Wakeham, A Guide to Drawing, Thomson/Wadsworth, 2007 ↩

- Porter, Fiber: Sculpture, 1960-present, 15 ↩

- Joan Simon and Susan C. Faxon, Sheila Hicks: 50 Years, Yale University Press, 2010, 91 ↩

- Mysliwiec, Danielle, “Sheila Hicks”, The Brooklyn Rail, April 2, 2014 ↩

- Simon, Faxon, Sheila Hicks: 50 Years, 171 ↩

- Sheila Hicks, “Sheila Hicks,” official website ↩

- Hicks, “Sheila Hicks” ↩