By Charlotte Seaman

Figure 1: Laylah Ali, B Drawing, 1998, graphite, color pencil and watercolor on paper, dimensions: 15 1/8 x 11 1/4 in. located in the Smith College Museum of Art, Northampton, Massachusetts, Purchased with gifts from the Fred Bergfors and Margaret Sandberg Foundation and the Richard and Rebecca Evans (Rebecca Morris, class of 1932) Foundation Fund

Contemporary artist Laylah Ali uses drawing in a distinct way, to depict scenes that are subtly less narrative, less violent, and more playful than those in her paintings. In this essay I will primarily discuss Ali’s 1998 drawing, located in the Smith College Museum of Art, titled B Drawing, as well as her “Greenheads” series of paintings. I will contrast her use of two media, drawing and gouache, and explore how she uses them differently to portray issues of race, gender, violence and power. Ali draws on a rich history of drawing as a medium to depict more personal and spontaneous works of art.

Ali was born in Buffalo, New York, in 1968. She had a mild interest in art as a child, but when she went to college she decided to officially pursue it. Ali received her degree in Studio Art and English from Williams College, in Williamstown, Massachusetts in 1991, and went on to receive her MFA from Washington University in Missouri. Ali cites bad television, in particular the flatness and color palette of old television cartoons, as an influence on her work and the work of others in her generation. She moved from the cartoon imagery she grew up with to more complex sources of inspiration. Ali clips images and headlines from newspapers, and keeps them in detailed and labeled files, using these clips to find patterns in the news and world, but also for assistance in drawing specific gestures and facial features. Ali is also interested in how people interact in these photos. She says, “I’m usually interested in the power dynamic of the story in the photo.”1 Ali uses these images to inform her work, but she isn’t making work directly inspired by her surroundings. Instead she follows a more drawn out process in which ideas and concepts inform her and are then expressed through the work. For this reason Ali feels she can’t talk about what a work is about while it’s still in progress. The artist instead prefers to make something, then step away and process it, after which she is able to talk about it.2

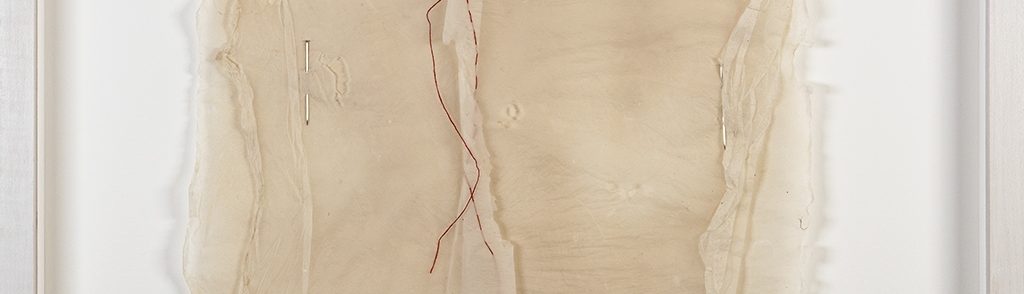

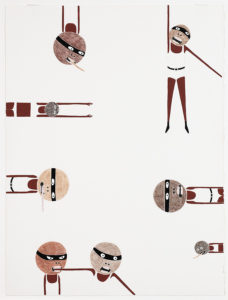

In B Drawing (fig. 1),3 Ali uses a traditional drawing medium, pencil, as well as watercolor, to depict a scene that is more playful, less narrative, and less deliberately ambiguous, than the paintings in her “Greenheads” series. The drawing consists of eight brown figures with large ball-shaped heads, spread out along the border of the paper in various positions and sizes. All eight figures are wearing white outfits, though it is unclear if these are tank tops, underwear, or some sort of superhero costume (a possible reference to comic books and cartoons). Some of the figures wear belts, and some have thin black masks covering their eyes, though they are still able to see since we can see their eyes through slits in the mask, referencing both superhero cartoons as well as cartoon robbers or villains. The figures are essentially genderless, although some wear two piece outfits while others wear one piece, which suggests a gendered difference. All figures have their mouths open, although not all in the same way: seven of the figures are baring their teeth in an ambiguous smile or growl, three have their tongues hanging out, and some have both bared teeth and a dangling tongue. Gravity is semi-suspended in this work: while the figures on the left side are all upright, the figure at the top right seems to be hanging upside-down, threatening to fall. There are no interactions between the figures except for the two at the bottom, who are in some sort of confrontation. The righthand one of the two has his hand in the other’s mouth, seemingly being bitten by the figure on the left. The left figure has a slanted eye shape, indicating anger, while the right figure has spherical eyes indicating surprise, so it can be presumed that the left figure is the aggressor and the right is the victim. The heads of these figures have almost no detailing, except for comically tiny detailed teeth.

The heads of the figures are drawn with colored pencil, while the bodies are done in watercolors. The white “suits” that they wear are the original paper left blank. The watercolor of the bodies is opaque, almost resembling acrylic, or Ali’s more typical medium of gouache. The sketching of the colored pencil on the heads is obvious, and there is a distinct textual difference between the heads and the bodies. For almost all eight of these figures, it’s impossible to read the expressions on their faces. A viewer can speculate, but there are very little signs or clues to help. This ambiguity is a key component of Ali’s style, represented here in the ambiguity of facial expressions. Another aspect that is repeated in later works is the mirroring of the spherical shape of the head in the nostrils and eyes of the figures.

Another work in the series provides further evidence of Ali’s drawing style. Titled B Drawing (fig. 2), it was made in 1996 from gouache and pencil on paper. This piece features similar characters to the Smith B Drawing, specifically, two figures in the same white outfits, with the same large ball-shaped heads. These figures have different shades of brown heads, but the same shade of body, and the same tall black socks. The left figure has a very long tongue sticking out of its mouth, and its eyes have a flat top, giving it a sad and dismayed expression, while its arms hang limp at its side. The right figure looks angry, portrayed through almond shaped eyes and an open, toothy mouth. It seems to be pointing and yelling at a spot on the ground, or possibly something out of frame that the viewer can’t see. In both B Drawings, Ali introduces characters but no narrative. The characters raise questions, but fairly simplistic ones. Ali has emphasized simplicity in these works, which she consciously calls “Drawings.” Ali’s use of drawing materials to portray cartoonish and playful scenes draws on a rich history of caricature and comic drawing.

To understand how Ali’s drawings fit into the history of the medium, it is useful to look at the way that drawing as evolved as a skill and as a form of art. Up until the late 1900’s learning to be an artist meant, first and foremost, going to art school to learn how to draw.4 Not only was education widely regarded as the first step to being an artist, but it was seen as a continual learning process. Artists were expected to be constantly continuing to learn and improving their skills, to the point that it was almost a grueling practice, as Deanna Petherbridge explains in her book The Primacy of Drawing: “the motto nulla dies sine linea [never a day without a line] therefore encompasses a huge range of contradictory ideologies from desire to punishment. The elevation of hard work into a ruling obsession … became one of the defining traits of the fully fledged romantic artist.”5 While drawing is still widely practiced today, until recently it wasn’t held in the same high regard, and was often seen more as an unfinished, preparatory medium.

Ali’s work is not grounded in the academic tradition, however it is informed by the rich history of caricature, especially as humorous or mocking social commentary. Petherbridge explains the importance of caricatures: “The prevalence of social commentary in broadsheets and political prints in the eighteenth century is surpassed only by the proliferation of journals in the nineteenth century publishing satirical caricatures and narrative ‘cartoon’ sequences.”6 Caricatures used in social commentary were some of the earliest examples of cartoons and comics. They were thought to show more truth than real life, presumably because caricatures tend to make internal characteristics external. In her work, Ali uses the visual language of cartoons, comics, and to some extent caricatures. Notably, though, her work is opposed to racial caricature in that it does not exaggerate features of an individual – rather the opposite: it turns individuals into signs or ciphers of generalized (though still racialized) human experience, which we see in her B Drawings.

Ali’s drawings have a number of parallels with caricature drawing. Some of these include her social commentary, as well as the violent, grotesque aspect that is often seen in caricature. However, Ali rejects a number of important aspects of caricature art. Visually, her figures are quite different than a caricature. Rather than greatly exaggerating aspects of the body, Ali does the opposite and standardizes her characters, so much so that they lose any aspect of individuality. Caricatures are traditionally biting yet humorous. But when asked about humor in her work, Ali said that she doesn’t see humor as the right word to describe it. She views her paintings as more absurd than humorous.7 Any humor comes after the fact, rather than during the making of the work.

There is also a long history of using caricatures in a racist fashion against African-Americans, over-exaggerating features to separate and dehumanize non-white people. Artist and illustrator C.M. Campbell tackles this topic in his poignant recent comic for online art magazine Hyperallergic called “How to Draw a Black Guy”: “I want to touch on exaggerated features. If the black guy’s features are consistent with the setting it feels natural and distinguished. But if the features contrast the settings the black guy comes across as laughable and buffoonish.”8 Although her “Greenheads” series, which I explore below, references the violent history of race relations, such as through KKK robes and nooses, Ali rejects the stereotypical depiction of black people altogether, preferring to have other aspects of the work speak to race. While her B drawing displays people of different races interacting, as signaled by the different head colors, it resists any attempt to characterize the power struggles as more systematic than isolated interpersonal situations.

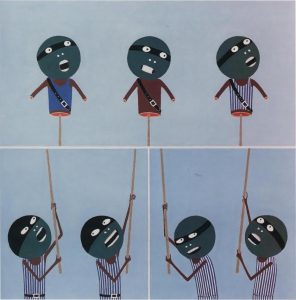

Ali’s approach to paintings involves some similar images and themes as in her drawings, yet to different effect. Ali created her “Greenheads” series of paintings between 1996 and 2005 with similar aesthetic to the “B Drawing” figures. All “Greenheads” figures are set on a blue background, with green heads rather than brown heads. If B Drawing raises few questions about narrative, “Greenheads” addresses more serious subjects and issues, bringing in themes of violence, power, history, and race. For example, Untitled (fig. 3), made in 1996 in gouache on paper, is made of three panels: one long horizontal panel with two squares underneath it. In the top panel there are three figures. All three figures consist of torsos stuck onto wooden posts, with their bottom halves and arms from the elbow down appearing cut off, as if they were models or toys. All three have the requisite green head, black masks over their eyes, and brown bodies. They look in three different directions, and all wear black belts strung across their chests. In the bottom left panel are two similar figures, both wearing blue and white striped bodysuits with black belts around their waists and black masks covering their eyes and head. Both of these figures hold up wooden sticks, apparently the same wooden sticks on which the top panel figures are stuck, but the sticks don’t connect through the break in panels. The bottom right panel also includes two figures, wearing the same striped shirts and eye masks as the left panel. These figures also hold sticks that don’t connect with the top panel. All three panels feature a bright, sky blue background. A number of questions about narrative, character roles, time and space settings are raised here. Who are the victims and who are the aggressors in this scene? Are the figures in the different panels even involved in the same narrative? Ali makes no attempt to answer these questions. She simply suggests that there are more people holding up the figures than being held up, and implies that these are just a few of a much larger number of figures.

In her essay on Ali’s exhibition at the Institute of Contemporary Art Boston, Suzanne Wise describes Ali’s comic book-style drawings as follows: “creating a world with a fake blue sky, stick figured alien-heads, a white platform earth and cinematic cropping of characters, Ali references the mediums of film, TV and comic strip. The ‘low culture’ art forms that kids love, the first and only art forms for many.”9 Although Ali says she is not especially well versed in the comic and cartoon world, she does use similar visual language and semiotics. The bright colors and simplified body shapes that Wise mentions are the largest similarity, however the separation of a work into multiple panels, such as the “Greenheads” Untitled discussed earlier, is also reminiscent of a comic book. However Ali’s “Greenheads” series also blatantly rejects some aspects of cartoon and comic art, primarily in its lack of narrative. While the objective of comic books is to provide an illustration to a narrative, Ali’s work suggests a narrative but does not fulfill it.

The presence or lack of a narrative in “Greenheads” and “B Drawing” illustrate a key difference. Ali has said that in both series she wanted to created figures that act as a question mark.10 This question mark can be a stand in for a number of questions: what is it? Who is it? Why is it doing that? The “Greenheads” are often depicted in scenes that are both violent and ambiguous. It is usually unclear who is the victim and who is the perpetrator. Ali gives the audience clues to certain aspects of the scenes, but often these clues bring up more questions, rather than answer them. These clues can consist of props like belts, which have a domestic violence connotation, or signals of racial violence, like nooses or robes that resemble those worn by the Ku Klux Klan. Ali is fascinated by dodgeball, a school game that targets the weakest in the class, and often includes characters holding dodgeballs, as a symbol of that violence. These clues, however, are easy to misread. Such is the case with the dodgeballs, which were widely mistaken by critics to be basketballs[11.”Art in the 21st Century: Laylah Ali in ‘Power’“], a symbol entrenched in the history of urban black communities and the media representation of African Americans. While Ali’s earlier work focused more on the moment of violence, her later work in the “Greenheads” explores the moments before and after violence.

A crucial difference a viewer might notice between Ali’s “Greenheads” and her drawings is medium. “Greenheads” are painted in gouache, which Ali finds can be extremely frustrating and finicky to work with11, but with a preferable outcome, more velvety and soft than an acrylic. The Smith B Drawing is done in colored pencil and watercolor, both much quicker materials. About the choice of medium Ali has said: “my hands would have preferred to make loose, expressive, large paintings – but that is not what they needed to do, not in the case of these paintings…drawings, for me, are usually more spontaneous.”12 Ali uses these two media to express similar subject matters, but distinctly different emotions in these works.

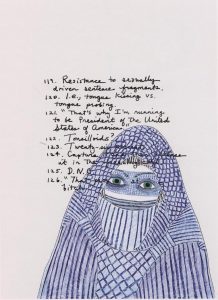

After “Greenheads” Ali went on to do a series entitled “Note Drawings,” which is a series of drawings in ink, colored pencil, ballpoint and gouache on paper, that incorporate heads and figures layered with writing in Ali’s own script. In her book The Primacy of Drawing, Deanna Petherbridge explains that “the practice of illustrating letters with drawings, where the pen moves so readily between text and illustration, is a crucial connection in the verbal and visual puns of caricature located within the intermediate and hybrid zone of graphism.”13 Ali draws on this tradition in her “Note Drawings,” but with the added dimension of school-like notes, which integrate text and drawing into one work, blurring the line between the two in a way that gives the work a child-like energy. The characters in “Note Drawings” reference the “Greenheads,” but also depart from that work in their explicit references to race and gender. The handwritten notes, taken from a list of non-sequitur thoughts from the artist, add a textual component not present in the entirely two-dimensional “Greenheads.” Dina Deitsch, Assistant Curator at the DeCordova, where the artist had an exhibition in 2008, comments on the “Note Drawings” in her exhibition catalogue: “Despite the apparently haphazard nature of the texts (they are drawn from the artist’s collection of phrases, jotted down on scraps of paper) the notes are thoughtfully selected and composed with an almost poetic attention to rhythm and syntax.”14 The thread of violence remains in “Note Drawings,” but while the “Greenheads” explores group dynamics, these involve one-on-one dynamics and the artist’s own voice. Again, Ali uses a drawing medium to produce work that is less carefully composed, and closer to the artist’s mind and hand. Drawing has traditionally been considered the medium closest to the artist’s thoughts and emotions; by incorporating handwritten notes she gives the audience a glimpse into the artist’s mind.

In all of her work, but most prominently her “B Drawings” and “Greenheads,” Ali is interested in the power of violence, and the power of witnessing violence. The artist says, “I think of myself and many of the characters in my paintings as observers of the misdeeds that go on. They often do not intervene but they see what goes on, and that has psychological ramifications.”15 Ali creates figures, and places them in violent scenes, but gives them no verbal or narrative context. Verbal expression is not the only thing that Ali removes, though; she experiments in the “Greenheads” with removing various body parts and gestures. Ali is interested in experimenting with power through the image of the body, experimenting with how much she can remove while still creating a figure of power. Her work suggests that the expression of violence itself symbolically mars or disfigures people, taking away part of their humanity.

The representation of violence and power in Ali’s drawings always has a racial component. In the Smith B Drawing, race is more outright, as the heads of the figures are more naturalistic and all have slight variations in brown, suggesting that the figures exist in a world of multiple races. While the characters in “Greenheads” seem to exist in a world without multiple races, both the “Greenheads” and the figures in the Smith B Drawing have brown bodies. On creating the “Greenheads” with brown bodies, Ali has said that “they are brown because I need to examine why them being brown adds these layers of meaning that don’t exist otherwise.”16 She is interested in exploring the idea that a painting full of exclusively white people might be seen as having no racial themes, and yet a painting full of brown people can’t be seen this way. Ali incorporates various racial aspects in the works, but doesn’t outright identify their race, to explore how this changes how they are viewed. As a result, the audience is forced to make judgements about the race and gender of the figures depicted, and possibly reconcile their own racial or gender prejudices.

The “B Drawings” generally invite different questions about narrative than is the case with the “Greenheads,” although they raise some similar themes. Although the “Greenheads” series doesn’t include a narrative, it raises questions about one, while the “B Drawings” raise more questions about characters and relationships. The Smith B Drawing’s characters are less interactive, appearing to act independently of anything else going on in the work. The figure in the “diving” position on the left is reminiscent of a superhero, recalling Ali’s comment about bystanders witnessing violence. A superhero is someone who is active in a scene of violence, rather than a passive bystander. More passive is the figure at the top right, whose pose recalls the filmic trope of someone dangling from a cliff, at the mercy of the person standing on top of the cliff. This trope explores the balance of power and violence. Finally, the two characters at the bottom are engaging in an obvious act of violence, in that one is biting the hand of the other. However, none of these characters invite the same questions about public power and authority as the “Greenheads.” The diving figure on the left is not certainly definitively a superhero; the figure dangling from the top has no adversary from which to build a narrative; and the other three figures peeking in from the top and sides stick long tongues out for no apparent reason, in a gesture that could be read as childish, comic, or abject victimization. For the two figures at the bottom, it’s obvious who is the aggressor and who is the victim, but not what is going on. While the “Greenheads” often hold props, the figures in the Smith B Drawing have nothing. While the political references in the “Greenheads” make the figures tend to appear masculine, in B Drawing they could read as any gender or un-gendered. Both works raise questions, however the “Greenheads” suggest certain more specific questions about race and violence related to adult, public life, whereas the B Drawing leaves itself open to more free association and questions of childhood and play.

Lydia Yee poses several important questions in her article Brown Heads, Green Bodies: “if in the Greenheads’ world, gender and race do not exist or operate in expected ways, what kind of power structure is at work? What is the source of all the violent impulses?”17 Ali requires the audience to ask themselves these prodding, even disturbing questions when looking at the “Greenheads.” The Smith B Drawing doesn’t raise the same kinds of questions, but instead offers the viewer a more gentle and open-ended thought piece. While the B Drawings in general are more spontaneous and have fewer layers, as Ali notes, this is “because they are not so studied, they can capture something I didn’t anticipate, and they are more playful than the paintings, and more enjoyable to make.”18 By using a traditional drawing medium in an untraditional way, to express a more playful and spontaneous subject matter, Ali draws from a deep historical tradition of drawing, as well as pop culture.

Examining Smith’s B Drawing in comparison to Ali’s other drawings and paintings clarifies the way Ali uses drawing to portray something distinctly different than painting. The Smith B Drawing can provoke strong reactions, ranging from laughter to distress, which is one of its greatest strengths. While the “Greenheads” lead the viewer to a specific set of questions, the B Drawing is more open-ended. Although “Greenheads” drew a larger critical response, Ali’s drawings express something unique. In a style that initially appears simple and straightforward, her work inspires important questions about the nature of violence and identity. Ultimately, her work suggests that these issues can only be understood through the way they have been represented, both in popular culture and in art.

- Laylah Ali and Deborah Menaker Rothschild, Laylah Ali: The Greenheads Series (Williamstown: Williams College Museum of Art, 2012), 8. ↩

- “Art in the 21st Century: Laylah Ali in ‘Power,’” Art21, September 16, 2005. ↩

- I will refer to this work as the “Smith B Drawing,” as there are several other works by Ali also called B Drawing. ↩

- Deanna Petherbridge, The Primacy of Drawing: Histories and Theories of Practice (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2014). ↩

- Petherbridge, The Primacy of Drawing, 216. ↩

- Petherbridge, The Primacy of Drawing, 348. ↩

- Ali and Rothschild, Laylah Ali: The Greenheads Series. ↩

- C. M. Campbell, “How to Draw a Black Guy,” Hyperallergic, April 10, 2018. ↩

- Laylah Ali, Laylah Ali (Boston: Institute of Contemporary Art, 2001), 9. ↩

- Ali, Laylah Ali. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Ali and Rothschild, Laylah Ali: The Greenheads Series, 19. ↩

- Petherbridge, The Primacy of Drawing. ↩

- Laylah Ali, Laylah Ali: Note Drawings (Lincoln, MA: Decordova Museum and Sculpture Park, 2008), 3. ↩

- Allen Isaac and Laylah Ali, “Here Comes the Kiss: A Conversation Between Laylah Ali and Allan Isaac,” The Massachusetts Review 49, no. 1 (Spring 2008), 156. ↩

- Isaac and Ali, “Here Comes the Kiss.” ↩

- Lydia Yee, “Brown Skin, Green Heads,” Art in Print Review 7, no. 3 (December 2002), 47. ↩

- “Art in the 21st Century: Laylah Ali in ‘Power.’” ↩