A data bar has neither chocolate nor flour but is sweet all the same. A thousand of them vanished on my computer, making me full of sourness. But I am getting ahead of the story.

This week’s adventure in science begins with my one hour on the scanning electron microscope. Now, one hour is not much time and at this point in the semester I could have spared several; however, I was dubious that these samples would be worth even as much as an hour. These were a new set of samples from Joseph Hill of Penn State. I posted last March (and before) about the odd appearance of some of these samples. Since then, something else odd has been happening with them, namely as they sit around they get harder to image. In March, Joe had sent me a large batch of samples but because of *life*, I was working through them slowly. I found as June wore into July that they were getting increasingly difficult to image. This is weird. So much so that it accounts in part for the absence of these posts during the summer – the inexplicable behavior was depressing.

Growing frustrated, I asked Joe to send me a fresh set of samples, but no sooner had they arrived then Xena lost her source. Not the Warrior Princess but the sputter coater I use to put a thin film of platinum on the samples, which is necessary for imaging. The platinum source was exhausted and we had to order a new one. About six weeks elapsed before the new source was installed and I could have a look at the new samples, meaning that they had been sitting around for what could be too long. I didn’t know.

My worries proved well founded; the samples were difficult. In my hour on the scope, I was able to come up with a work around, that allows me to get images but at the cost of contrast – the kluge makes work possible but not ideal.

Coming back to the lab after that, I wanted to go back through the collection of saved images. The imaging had gotten so distorted this summer that the problem became inescapable; but, in the session this week, the problematic imaging was modest enough that I might have missed it had I not be suspicious. I was curious to see whether this particular imaging difficulty was present but unnoticed in the earlier work.

As I was working through, and happy to say, NOT seeing evidence of this distortion, I noticed that after sometime in March, the data bars were gone. Poof!

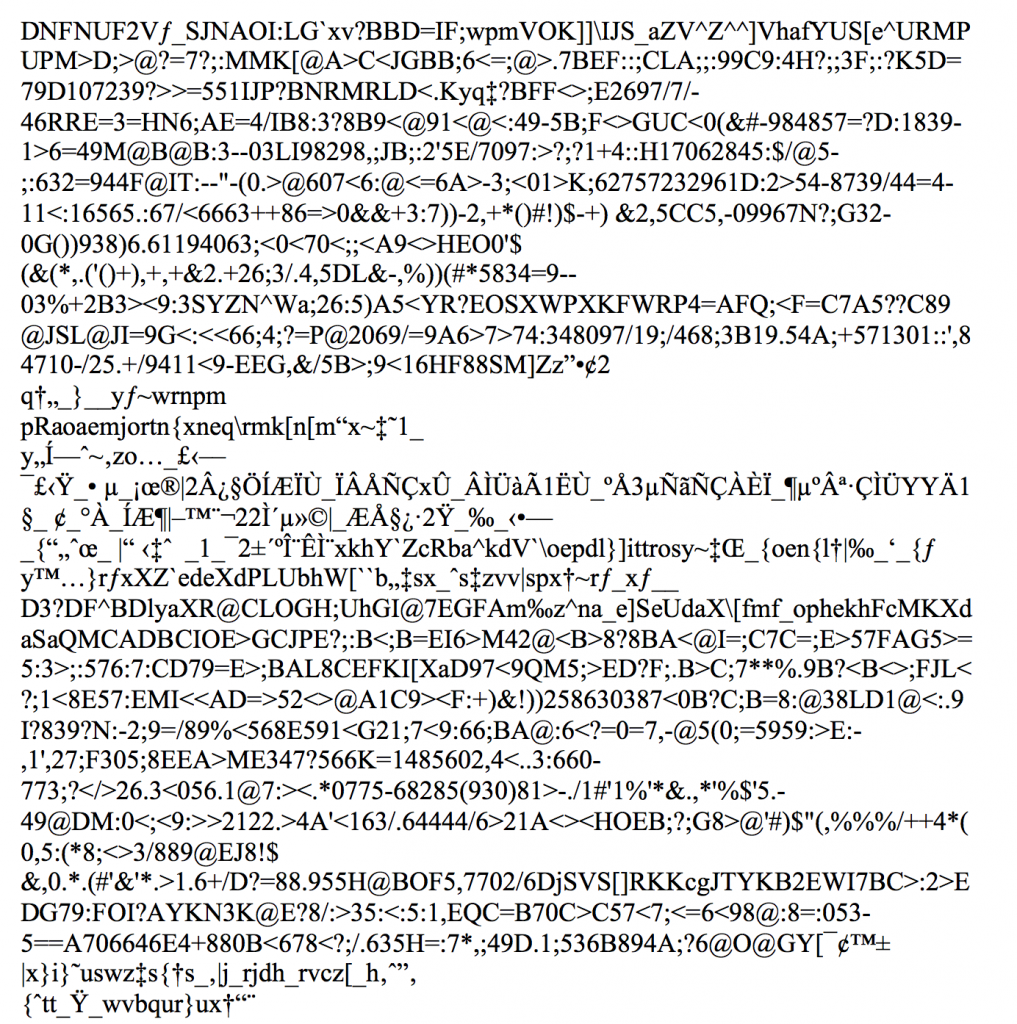

Here is a picture of a data bar (yum):

This displays relevant parameters of the microscope. WD is working distance, meaning how far the sample is from the surface of the lens; HV is accelerating voltage, which is one of the most important conditions of the scanning beam; curr is the electron current; mag is magnification, scaled to the monitor; det is detector used to make the image, the instrument has several of them; bias besides being the last four letters of my name, is a voltage that modifies the accelerating voltage; and the 400 nm bar shows a calibrated distance.

While I am working on the microscope, the data bar is displayed along the bottom of the image and updated in real time. Its customized to show things of interest to me. When I save an image, the data bar is saved too, where it sits at the bottom of the image. Of course, that overwrites the lower 5% or so of the actual image but since I am not seeing that anyway (it is behind the bar while I am running the microscope) and since the data in the bar are valuable, it is a fair swap.

Or it was being saved until mid-March. After that? No bar. Well, it turns out that buried in the software is a little check-box that says save the data bar and somehow this had become unchecked.

On the face of it, this sounds like a prize purple pestilence, particularly insofar as the magnification is essential. But I didn’t lose heart (completely) because of the design of the .tif format. Out there in the interwebs, images tend to be .jpg files. But on microscopes, we almost ways get .tif files. This tif stands for tagged image format, an industry standard where the first so-many bits of the image file are set aside for text (i.e., tags). If the microscope vendor is on the ball, their software fills those tags with the information in the data bar, and much more besides.

All right! That crucial information is probably saved with the images themselves. Yay! But how to view it. The first thing I did was to contact FEI, the company that makes the scanning electron microscope in question and ask them. One of their service reps told me that he does this in MS Word. Really? Well, yes. If you use the Open… dialog and select all files, then word will open the image file as text. It looks like this:

Or rather the first page of it does. The opened file has 681 pages looking about like this, and more than 1,300,000 characters. Happily, the last 10 pages or so contain all those tags, listing the magnification, accelerating voltage and so on.

OK, so that is good. But using MSWord like this is cumbersome. Thanks to the talented Michael Pound of the University of Nottingham, I can now type

LC_ALL=C sed -n -e ‘/Date=/,$p’ tagged.tif

into the terminal (where “tagged.tif” is the file name of the image in question) and the terminal displays only the tags, faster and easier than using MSWord. The coming challenge is to see if the tags can be written to text and if the whole process batched to chunk thru the hundreds and hundreds of files I have without their data bar.

Well the bigger challenge is to handle Joseph’s demanding samples. He has sent me yet another batch, they arrived Friday. I have started to prep them and plan to image this week. Either being fresh they will image properly, or being somehow prone to this artifact, they won’t and I’ll have to use the kludge. Stay tuned!