I heard via social media — maybe my Twitter feed? — that many museums and cultural venues in Massachusetts would be waiving admission on Fridays this summer. I checked the schedule online and noted that in August, I might be able to visit three museums in my area, on three successive Fridays. Today was Historic Deerfield, so in the early afternoon I headed up 116 then 5/10 to 8 Memorial Street in Deerfield, where the Memorial Hall Museum welcomed a horde of visitors, children included.

I heard via social media — maybe my Twitter feed? — that many museums and cultural venues in Massachusetts would be waiving admission on Fridays this summer. I checked the schedule online and noted that in August, I might be able to visit three museums in my area, on three successive Fridays. Today was Historic Deerfield, so in the early afternoon I headed up 116 then 5/10 to 8 Memorial Street in Deerfield, where the Memorial Hall Museum welcomed a horde of visitors, children included.

I had visited the Deerfield crafts show once decades ago, but I’m quite sure I was unaware of Memorial Hall Museum. How could I have missed it?! This three floor, 19-room museum opened in 1880, and according to the website,

The museum’s extraordinary collection of furnishings, paintings, textiles, and Indian artifacts is “the finest collection of local antiquities in New England” and is one of America’s oldest museums.

I started my tour on the top floor. One room was devoted to Tools, Trades, and Tasks and showcased artifacts for making textiles and shoes, for dairying, farming, and broom making, and for woodworking. Can you image that in 1845, Deerfield produced 56,425 pounds of butter and 12,125 pounds of cheese! And think about this: in 1855, 399,600 brooms were manufactured in Franklin County.

On the third floor I also visited the dining room, the Victorian bedroom with its pink walls (the color is officially “ashes of roses”), the sitting room with its wallpaper of gold, blue, and green, and the children’s room with its dolls, toys, and dollhouse. There was also an exhibit titled Skilled Hands and High Ideals — the Arts and Crafts Movement in Deerfield which showcases the works of talented women in basketry, embroidery, weaving, netting, and metalwork.

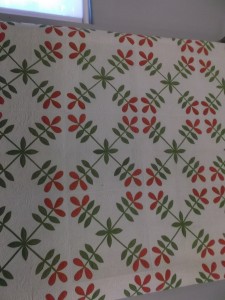

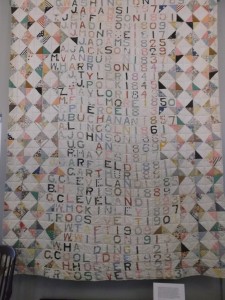

I think my favorite exhibit was the quilts. The most elaborate quilt in the collection was made with 82,000 pieces! (It didn’t photograph well.) Here are a few of my favorites (sorry about the quality of the photos — the lighting has to remain dim). This one lists the names of the presidents until FDR and their terms of office:

This one lists the names of the presidents until FDR and their terms of office:

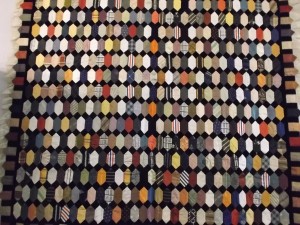

I admired the design of this one — it’s geometric but not so regular as to be boring:

I admired the design of this one — it’s geometric but not so regular as to be boring:

The second floor focused on the early history of Deerfield, including the interactions between the English settlers and the Native Americans. From my prior reading, I remembered the importance of Deerfield as one of the furthest outposts of English settlement. In fact, the 1704 attack on Deerfield became a defining moment in its early history. I think this door dates from that time:

The second floor focused on the early history of Deerfield, including the interactions between the English settlers and the Native Americans. From my prior reading, I remembered the importance of Deerfield as one of the furthest outposts of English settlement. In fact, the 1704 attack on Deerfield became a defining moment in its early history. I think this door dates from that time:

Archaeological evidence indicates that the Pocumtucks lived in this area of North America for 11,000 years, until English settlers founded the town in 1674 and then forced the natives out in 1676 (the Deerfield River was originally the Pocumtuck River). After King Philip’s War ended in August 1676, New England’s Native Americans were effectively marginalized, but they did not disappear. There was continued interaction with the dominant culture, and traditions, language, and direct descendants have survived.

Archaeological evidence indicates that the Pocumtucks lived in this area of North America for 11,000 years, until English settlers founded the town in 1674 and then forced the natives out in 1676 (the Deerfield River was originally the Pocumtuck River). After King Philip’s War ended in August 1676, New England’s Native Americans were effectively marginalized, but they did not disappear. There was continued interaction with the dominant culture, and traditions, language, and direct descendants have survived.

Also on this floor are a room devoted to the military, with the requisite uniforms, guns, sabers, and ammunition, and a room exhibiting clothing, with band boxes (hat boxes), a Singer sewing machine, Kashmir shawls, shoes, and nurses’ uniforms. I particularly admired the women’s fashionable dresses.

Insofar as a colleague had recommended it to me, I spent a bit of time in the exhibit titled Made of Thunder, Made of Glass II: Continuing Traditions in Northeastern Indian Beadwork. In all the history books, even the most retrograde, you hear about the Native Americans trading for glass beads, and I must say, I wondered why they found them so valuable. Perhaps this exhibit partly explains the reason. Artists of the Northeastern tribes, namely the Haudenosaunee, the Wabanaki (comprised of the Penobscot, Passamaquoddy, Maliseet, Mi’kmaq, and Abenaki), and the Mohawks in Canada, traditionally used bone (quills), shell, moosehair and hide; after the disruption caused by contact, the artists transitioned to using glass beads and textiles like velvet in their crafts.

I myself don’t care for what were called “whimsies” — I’m not a big fan of pincushions or hats or even decorative handbags — they’re what I call clutter, and I just don’t need it in my life. The exhibit did explain that before women’s clothes had pockets, women carried “reticules”; photographs from as far back as 1839 portray fashionable women carrying these small purses, often bead bags embroidered by Native Americans.

Doesn’t this look like a mouse? Could it be Mickey?

Doesn’t this look like a mouse? Could it be Mickey?

This bead bag is more to my taste, because it’s not very gaudy:

This bead bag is more to my taste, because it’s not very gaudy:

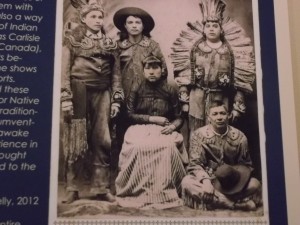

I hadn’t realized how in the nineteenth century, “being Indian” became one way of making a living for Native Americans. After all, in those days, anyone not wealthy or white faced a lot of obstacles to simply surviving (maybe not a lot has changed a century and a half later). Tribal members living in the areas around the tourist hot spots like Niagara Falls began making beaded souvenir trinkets for the tourist trade. Others participated in Wild West shows, such as this family:

I hadn’t realized how in the nineteenth century, “being Indian” became one way of making a living for Native Americans. After all, in those days, anyone not wealthy or white faced a lot of obstacles to simply surviving (maybe not a lot has changed a century and a half later). Tribal members living in the areas around the tourist hot spots like Niagara Falls began making beaded souvenir trinkets for the tourist trade. Others participated in Wild West shows, such as this family:

This exhibit, of over 250 examples of historical and contemporary pieces made between 1800 and 2015, emphasizes that the beadwork tradition has not died out. Included in the show are 16 portraits of contemporary artists, most of them women, by Gerry Biron. This one I found particularly striking:

This exhibit, of over 250 examples of historical and contemporary pieces made between 1800 and 2015, emphasizes that the beadwork tradition has not died out. Included in the show are 16 portraits of contemporary artists, most of them women, by Gerry Biron. This one I found particularly striking:

The artist is Rhonda Besaw; she’s Canadian Metis/Abenaki.

The artist is Rhonda Besaw; she’s Canadian Metis/Abenaki.

Finally, I moved down to the first floor. Here is a room devoted to architecture, a room set up like a school room with curiosities from around the world exhibited in glass cases, and also a large music room, with various musical instruments, including many pianos and organs. This one is a parlor organ:

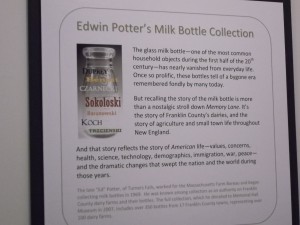

My last stop was to view the exhibit of milk bottles. I do remember milk delivered in glass bottles from the local dairy, but those days are gone now:

My last stop was to view the exhibit of milk bottles. I do remember milk delivered in glass bottles from the local dairy, but those days are gone now:

I could have spent a lot more time here, and it’s on my list of “places worth returning to.” I highly recommend this museum and the beadwork exhibit.

I could have spent a lot more time here, and it’s on my list of “places worth returning to.” I highly recommend this museum and the beadwork exhibit.