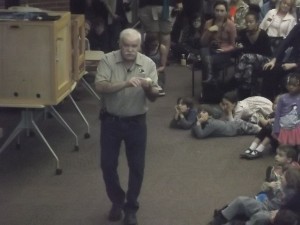

I don’t think I had ever been to the town, but my GPS got me close enough to the destination specified in The Last Green Valley Walktober brochure: the Rotary Park Bandstand in Putnam, Connecticut. At 1 pm, Municipal Historian Bill Pearsall (in orange T-shirt) began speaking to about 30 of us about Putnam’s Mill and Rail History; the walk and talk focused on the mills, the railroad, and the flood of 1955. You could describe Putnam, he began, by saying about it, “A river ran through it,” and “A railroad ran through it.” One of the original pioneers and settlers, Peter Aspinwall came to the area from New Roxbury, Mass (the current town of Woodstock, CT); his stepson operated the first sawmill in the settlement. The first cotton mill in Putnam dates back to 1807 with the founding of the Pomfret Manufacturing Company; eventually, six mills were in operation along the Quinebaug River, among them the mills of Rhodesville owned and operated by Mr Smith Wilkinson, the Morse Mill, the Powhatan Mill, and the Monohansett Manufacturing Company. As the mills developed, there was a need to bring raw materials in and finished products out; hence, the railroad came in to do both. The town fathers originally wanted to build a canal and even were granted a charter to do so, but that project never got off the ground. Instead, in 1839, the first railroad, the Norwich and Worcester line, opened to serve the area’s transportation needs.

I don’t think I had ever been to the town, but my GPS got me close enough to the destination specified in The Last Green Valley Walktober brochure: the Rotary Park Bandstand in Putnam, Connecticut. At 1 pm, Municipal Historian Bill Pearsall (in orange T-shirt) began speaking to about 30 of us about Putnam’s Mill and Rail History; the walk and talk focused on the mills, the railroad, and the flood of 1955. You could describe Putnam, he began, by saying about it, “A river ran through it,” and “A railroad ran through it.” One of the original pioneers and settlers, Peter Aspinwall came to the area from New Roxbury, Mass (the current town of Woodstock, CT); his stepson operated the first sawmill in the settlement. The first cotton mill in Putnam dates back to 1807 with the founding of the Pomfret Manufacturing Company; eventually, six mills were in operation along the Quinebaug River, among them the mills of Rhodesville owned and operated by Mr Smith Wilkinson, the Morse Mill, the Powhatan Mill, and the Monohansett Manufacturing Company. As the mills developed, there was a need to bring raw materials in and finished products out; hence, the railroad came in to do both. The town fathers originally wanted to build a canal and even were granted a charter to do so, but that project never got off the ground. Instead, in 1839, the first railroad, the Norwich and Worcester line, opened to serve the area’s transportation needs.

We began our walk along a section of the river that was originally part of the Mill Pond. In fact, the area was long prone to flooding: in 1936, there were two floods, in 1938 a major hurricane, and in 1955, two tropical storms struck the same week, and 17 inches of rain fell in 24 hours. Water, which seeks its own level, came down the railroad tracks, and Long Bridge was washed out. The town decided it had had enough, and the Army Corps of Engineers was brought to help with flood control. The West Thompson Dam was constructed at this time, with the express purpose of protecting downstream towns like Putnam. The photo below is of the stone dam; I think we’re looking north or east.

This old mill building (below) features rubble construction and a square abutment (for hoisting and for the staircases). Note the regularly spaced diamond-shaped iron brackets, which were used for internal supports.

This old mill building (below) features rubble construction and a square abutment (for hoisting and for the staircases). Note the regularly spaced diamond-shaped iron brackets, which were used for internal supports.

The photo below is of the old Nightingale Mill, also of stone construction. Note the same square abutment and diamond-shaped iron brackets.

From our twenty-first century vantage point, it’s almost difficult to imagine how these textile mills transformed an area. Putnam, which was not incorporated until 1855 from sections of Killingly, Pomfret, and Thompson, was originally a small farming community, and there weren’t enough local townsfolk to staff the mills. Thus began waves of immigration into town: French-Canadians, Italians, and others, who lived in distinct neighborhoods and kept up their own traditions. The mills also employed women and children, providing them with the first cash income they ever had.

From our twenty-first century vantage point, it’s almost difficult to imagine how these textile mills transformed an area. Putnam, which was not incorporated until 1855 from sections of Killingly, Pomfret, and Thompson, was originally a small farming community, and there weren’t enough local townsfolk to staff the mills. Thus began waves of immigration into town: French-Canadians, Italians, and others, who lived in distinct neighborhoods and kept up their own traditions. The mills also employed women and children, providing them with the first cash income they ever had.

From Kennedy Drive, we crossed the Quinebaug on Providence Street. Here we paused for an interesting story about the 1955 flood. One of the old mill buildings was being used for storage of magnesium (who knows why), and when the flood waters swept in, the barrels broke out of the warehouse. When the metal came in contact with the water, it exploded. This event was the original Water Fire! Older residents say they still remember how the magnesium flares lit up the night.

Turning back the way we came but on the other side of the river, we continued the walk along Church Street, where we noted that some of the houses were those originally built for the factory workers. When we paused by the dam, Bill told us that it is still being used to generate hydroelectric power. In fact, two dams in Putnam now generate electricity; these “run-of-river” hydroelectric plants are deemed less detrimental to fish spawning and have less negative environmental impact. Four centuries after the river’s potential was observed by colonial settlers, the river’s 52 foot drop is still being harnessed to generate power.

A number of historical buildings line Church Street. The Putnam Courthouse, which we passed on the left, used to be a mill; across the street was a grocery store. Back at the turn of the twentieth century, word got around to the men riding the rails that there was often discarded food at the store, and they would congregate there. In 1904, a huge fire destroyed the church next to the grocery store. The current Town Hall was the original high school. In line with this re-purposing of buildings, Catholic sisters now own the Morse Mansion; insofar as Mr Morse was one of the wealthy mill owners, the mansion has beautiful interiors, with ten-foot ceilings and black walnut woodwork.

At Route 44, we crossed over the Quinebaug again (originally built in 1923, the bridge is currently under construction) to pick up the River Trail close to where we started our walk. Doesn’t the River look serene from this vantage point?

The house pictured below was the boyhood home of John Dempsey, six term mayor of Putnam, who was instrumental in getting the town rebuilt after the devastating 1955 flood. By that time, the textile industry was mostly gone, but the remaining home and business owners needed a lot of help getting back on their feet. Although he was loyal to his local constituency and reluctant to leave Putnam, Dempsey eventually served as ten years as governor of Connecticut.

The house pictured below was the boyhood home of John Dempsey, six term mayor of Putnam, who was instrumental in getting the town rebuilt after the devastating 1955 flood. By that time, the textile industry was mostly gone, but the remaining home and business owners needed a lot of help getting back on their feet. Although he was loyal to his local constituency and reluctant to leave Putnam, Dempsey eventually served as ten years as governor of Connecticut.

Back on River Trail again, we continued walking west, with Bill pointing out sites of historical interest. If I’m reading my notes right, the ruin in the photo below was the first mill in Putnam.

Back on River Trail again, we continued walking west, with Bill pointing out sites of historical interest. If I’m reading my notes right, the ruin in the photo below was the first mill in Putnam.

Basing his conclusion on interpretation of the written records, Bill suggested that this junction is where Daniel Aspinwall originally landed in Putnam.

Basing his conclusion on interpretation of the written records, Bill suggested that this junction is where Daniel Aspinwall originally landed in Putnam.

Speaking again about the 1955 flood, Bill told us that after the water receded, the town needed to get rid of all the debris somehow, so they used a lot of it as fill on the river banks. You can see in this photo that mixed in the soil there is some fibrous, non-natural material. Earlier uses of this area included a Native American fish weir and a nail-and-pin factory.

Speaking again about the 1955 flood, Bill told us that after the water receded, the town needed to get rid of all the debris somehow, so they used a lot of it as fill on the river banks. You can see in this photo that mixed in the soil there is some fibrous, non-natural material. Earlier uses of this area included a Native American fish weir and a nail-and-pin factory.

The end of the walk brought us to where the railroad crossed the river, on a bridge high above the still-standing footbridge that you see in the photo. After the 1955 flood, the railroad bridge was not rebuilt. Although at one point in time two railroads intersected here, making Putnam a transportation hub, the general decline in rail traffic of course affected the town. In fact, in the state of Connecticut, rail mileage steadily declined from a high of over 1000 miles of track in 1920 to only about 330 miles today.

The end of the walk brought us to where the railroad crossed the river, on a bridge high above the still-standing footbridge that you see in the photo. After the 1955 flood, the railroad bridge was not rebuilt. Although at one point in time two railroads intersected here, making Putnam a transportation hub, the general decline in rail traffic of course affected the town. In fact, in the state of Connecticut, rail mileage steadily declined from a high of over 1000 miles of track in 1920 to only about 330 miles today.

We all thanked Bill for his presentation, then the group drifted apart. I walked quickly back to the downtown area, which remained a lively scene through the waning afternoon. Putnam celebrated Pumpkin Fest today, with vendor booths, street musicians, and those kinds of festivities, but I was feeling rather chilled and tired and headed for my car and home.

We all thanked Bill for his presentation, then the group drifted apart. I walked quickly back to the downtown area, which remained a lively scene through the waning afternoon. Putnam celebrated Pumpkin Fest today, with vendor booths, street musicians, and those kinds of festivities, but I was feeling rather chilled and tired and headed for my car and home.