I read in the local paper last week that the Quaboag Historical Society would be offering a bus tour of three old cemeteries in the former Quaboag Plantation. “Fascinating, I’m in,” I said to myself and signed up immediately. The weather was chilly and miserable this afternoon, but all of us who showed up at noon today at the old train depot in West Brookfield eagerly climbed aboard the bus, and led by Ed Londergan and Amy Dugas, we were off on our adventure.

Most of the graves in the cemeteries we visited today date from mid-1700 through the late nineteenth century. Although gravestones are not the primary records consulted by demographers, even a cursory glance at the dates on these stones forces one to acknowledge that most people did not live to a ripe old age. Infant mortality was high; children died before reaching their teens; women died in childbirth. Contagious diseases such as flu and smallpox swept through the colonies, and middle-aged adult males frequently died of accidents. In the early years of European settlement, field stones and wooden stakes marked graves, and these of course have disappeared. Only when villages became more well-established did cemeteries with their headstones (and sometimes footstones) start appearing.

Historians who have studied the gravestones have noted broad trends in the carved motifs and inscriptions. The earliest gravestones with their lurid skulls emphasized mortality, then in the Puritan era, winged cherubs emphasized the resurrection. In the nineteenth century, during the Greek revival period, carvings of urns with willows were favored. A variety of other motifs were also in vogue, including floral decorations such as vines and leaves, geometric designs such as repeating lozenges, columns on both sides of the inscription tablet, and finials.The gravestones themselves took on different shapes, including arches with square or rounded shoulders; some families even went in for obelisks. It is believed that bodies were generally placed behind the stones, so that people would not step on them; bodies were also placed so that when they were called to rise, they faced their Maker.

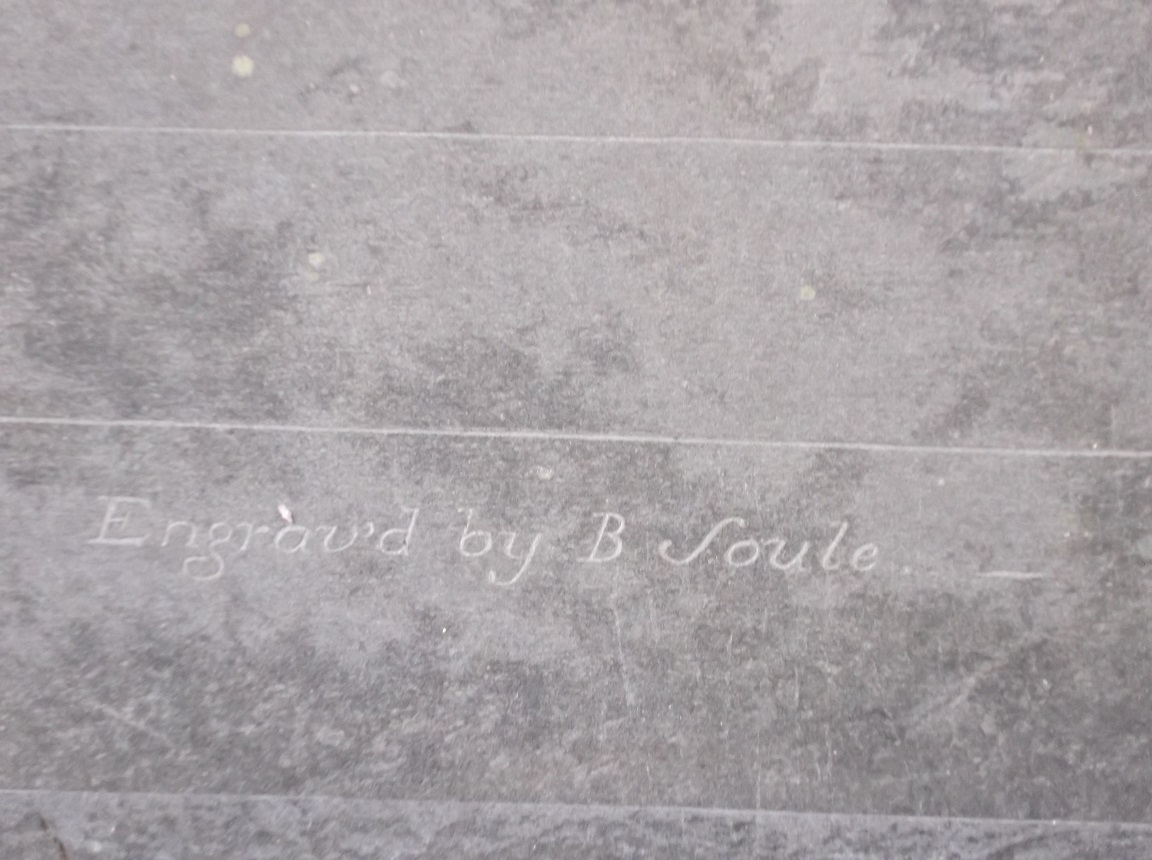

Gravestones were carved from different types of stone quarried from all over New England: materials included slate, sandstone, schist, and marble. Some of these stones are more susceptible to weathering than others, particularly those which attracted lichen, and nearly three centuries later, inscriptions on the softer stones are almost unreadable. Gravestone carvings are now considered outstanding examples of early American folk art; some of the carvers even signed their work, indicating their awareness of their artistry.

We started our tour in West Brookfield, at the Old Indian Cemetery. The Foster family, whose plot this is, was headed by Jedediah Foster, lawyer, judge, colonel in the Revolutionary War, and one of the three men appointed to draft the Massachusetts constitution.

The Foster family, whose plot this is, was headed by Jedediah Foster, lawyer, judge, colonel in the Revolutionary War, and one of the three men appointed to draft the Massachusetts constitution.

Note the rosette motif and the rays of the rising sun (these are typical of older carvings): This is the monument to the Haymakers, a group of men who died in 1710, the last settlers to be killed in an Indian attack in Quaboag Plantation (we don’t think the men are actually buried here).

This is the monument to the Haymakers, a group of men who died in 1710, the last settlers to be killed in an Indian attack in Quaboag Plantation (we don’t think the men are actually buried here).

This is a beautiful example of the winged skull.

This is a beautiful example of the winged skull. The Soule family of Barre were skilled carvers and talented gravestone artists.

The Soule family of Barre were skilled carvers and talented gravestone artists. We’ve now travelled to North Brookfield, to the Maple Street Cemetery, which is also known as the Old Burial Ground (the latest burial here dates to 1957). The burial vault in one corner of the cemetery is lined with brick; this is where they stored bodies in the winter, when the ground was frozen and graves could not be dug.

We’ve now travelled to North Brookfield, to the Maple Street Cemetery, which is also known as the Old Burial Ground (the latest burial here dates to 1957). The burial vault in one corner of the cemetery is lined with brick; this is where they stored bodies in the winter, when the ground was frozen and graves could not be dug.

Here is an example of a double headstone. This is a fine example of the fleur-de-lis motif. I was surprised to see this, as I understood the symbol to be associated with royalty and with France, a historically Roman Catholic nation.

This is a fine example of the fleur-de-lis motif. I was surprised to see this, as I understood the symbol to be associated with royalty and with France, a historically Roman Catholic nation. We’re standing at the burial plot of the Walker family. Businessman, president of the Boston Temperance Society, lecturer at Oberlin, Harvard, and Amherst College, US congressman, and anti-slavery activist, Amasa Walker was one of North Brookfield’s shining lights. He died in 1875, as the inscription shows.

We’re standing at the burial plot of the Walker family. Businessman, president of the Boston Temperance Society, lecturer at Oberlin, Harvard, and Amherst College, US congressman, and anti-slavery activist, Amasa Walker was one of North Brookfield’s shining lights. He died in 1875, as the inscription shows. Oliver Ward was another of North Brookfield’s outstanding citizens. There is very little ornamentation on this stone, but the carver did use block letters for the name and a more italicized type for the date and his age.

Oliver Ward was another of North Brookfield’s outstanding citizens. There is very little ornamentation on this stone, but the carver did use block letters for the name and a more italicized type for the date and his age. Aren’t these odd looking? We think these are children’s graves.

Aren’t these odd looking? We think these are children’s graves.

Look at this lovely willow and urn. The short hatch marks in the background are known as “walking the chisel” carving.

Look at this lovely willow and urn. The short hatch marks in the background are known as “walking the chisel” carving. Our third and last stop was in New Braintree. We paused briefly at the New Braintree Historical Society for refreshments and to warm up, then we hiked up the hill to the Church Cemetery.

Our third and last stop was in New Braintree. We paused briefly at the New Braintree Historical Society for refreshments and to warm up, then we hiked up the hill to the Church Cemetery.

Here is an example of an obelisk marker:

Among the early settlers of New Braintree was the Reverend Benjamin Ruggles, 1700-1782. Benjamin’s brother Timothy had a son, Timothy Dwight Ruggles, whose spouse Bathsheba was convicted of murder and hanged. As a Loyalist, Timothy Dwight did not find America hospitable and re-located to Nova Scotia.

Among the early settlers of New Braintree was the Reverend Benjamin Ruggles, 1700-1782. Benjamin’s brother Timothy had a son, Timothy Dwight Ruggles, whose spouse Bathsheba was convicted of murder and hanged. As a Loyalist, Timothy Dwight did not find America hospitable and re-located to Nova Scotia.  This Ware family member gravestone is barely legible. Their son Timothy died when he was struck by lightning.

This Ware family member gravestone is barely legible. Their son Timothy died when he was struck by lightning. John Grainger‘s story is a fascinating one. In 1775, he marched a company of Minutemen from New Braintree to Cambridge. As the plaque tells us, during the Revolutionary War, he fought at Bunker Hill and at the siege of Boston.

John Grainger‘s story is a fascinating one. In 1775, he marched a company of Minutemen from New Braintree to Cambridge. As the plaque tells us, during the Revolutionary War, he fought at Bunker Hill and at the siege of Boston. Dan Hamilton, who has a personal connection to this land, stands in front of a field that was owned by the Warner family, who also owned a tavern on the other side of the cemetery. Legend has it that Daniel Shays of Shays Rebellion fame hid there when he was on the run from US troops.

Dan Hamilton, who has a personal connection to this land, stands in front of a field that was owned by the Warner family, who also owned a tavern on the other side of the cemetery. Legend has it that Daniel Shays of Shays Rebellion fame hid there when he was on the run from US troops.

I tried my best to absorb all the facts we learned about our fellow citizens who lived here before us, but it was a lot to take in. I’m glad historians have recognized that these gravestones are rich in both history and beauty and have taken the time to try unlocking their secrets.