As I mentioned in a recent post, I don’t tend to use this blogging medium to critique musical and theater performances I attend. Likewise, I attend more art exhibits than I blog about for the same reason: a reluctance to pretend that I am any kind of art critic. I’m not making an exception in this post; instead I’ll talk about the four art exhibits I visited over the past few weeks using facts rather than a lot of personal opinions.

On Thursday the 14th, I took the day off from work and drove to downtown Hartford to see a show at the Wadsworth Atheneum titled Gothic to Goth: Romantic Era Fashion & Its Legacy. Although there’s a lot of construction going on around it, the museum is right off I-84, and there’s validated $3 parking in a lot a few blocks away, so getting there wasn’t a problem. The Atheneum is a lovely museum with some outstanding pieces and you could spend a whole day or more there, but I didn’t have much time and limited myself to viewing the costume exhibit in the third floor special exhibition gallery.

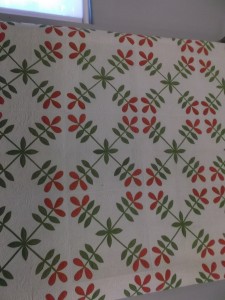

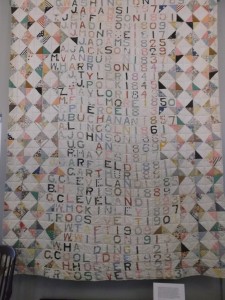

Romanticism is a term used by historians to describe a literary and artistic movement that influenced European and North American culture in the early to mid-nineteenth century. The practitioners emphasized the role of imagination and emotion in human life, perhaps in reaction to both industrialization and Neoclassicism. The exhibit covers the years 1810 to 1860 and also includes modern, twenty-first century costumes whose creators were influenced by this movement (think Goth fashions and steampunk). The curators have done an excellent job untangling the various strands in the Romantic movement: they discuss American authors like Poe and Hawthorne, British authors like Walter Scott and Lord Byron, as well as science fiction writers like Verne and Wells; they link religious revivals, Transcendentalism, and the Hudson River School of painting. In describing women’s clothing, they point out how elements such as slashed sleeves imitate Renaissance models and how the corset forced women’s outlines into the medieval Gothic arch shape (this seemed a bit of a stretch to me). Even accessories like capes, caps, combs, purses, beaded bags, earrings, scarves, and shawls incorporated elements of the prevailing world view, not to mention housewares like ceramics, painted furniture, tinware, glass, and quilts.

I was especially interested in the wedding outfit worn by Olive Harrington of Brookfield; it’s a silk ensemble commissioned by Olive’s sister when she worked as a missionary in Burma. Of course it is not white; white bridal gowns only came into vogue when Queen Victoria wed Prince Albert in 1840. Speaking of Victoriana, one of the cases displayed jewelry made with human hair; for some reason, this made me a bit queasy — I’m rather relieved that this sentimental mania eventually faded away.

On Sunday the 17th, I was in Monson for a hike at the town’s recently conserved Flynt Quarry Lands, so when I was done there, I drove to the downtown area and parked outside 200 Main Street, which is the House of Art. From April 16 until Sunday May 1, the Monson Arts Council 23rd Annual Spring Art Exhibition and Sale is open on the weekends. They are calling it Deep, as in the synonym for ocean, but I’m not exactly sure why and couldn’t find an explanation in the promotional materials. This is a juried show with pieces worked in different media: oil, pastel, watercolor, acrylic, fiber, wood, photography, prints, graphite, and with found objects. The brochure lists the prize winners (with photos of each piece) as well as contact information for each participating artist. The judges’ decisions are clearly marked next to the labels, so one can’t really look at the art and select one’s own favorites without being influenced by the professional evaluation. All the same, I did try to gauge my own reaction to each piece, and I have to say that overall I do agree with the judges. The winning entries are certainly deserving — whether because of the artist’s unique vision or outstanding technical skill. “Best of Show” was a ravishing oil painting titled Reflection; I also admired the first prize in painting, which was also an oil, titled Spring Street. The other piece I liked was awarded the second prize for photography; it was an inkjet print titled Closest Softest Neighbors.

This afternoon I picked up a museum pass from the Haston Public Library and drove to the Worcester Art Museum to see the show Cyanotypes: Photography’s Blue Period. It was fascinating and eye-opening; I don’t think I’ve ever seen anything like it. I’m not even sure who curated the show (I know Clark University students worked on it), but the art historians did an excellent job. The show has had glowing reviews in the New York Times, the Boston Globe, and the Worcester T&G. It does close this weekend, so I encourage you to see it now.

A cyanotype, as I understand it, is a photograph made with an iron-salt solution and light; the image resulting from exposure is colored blue. Thus cyanotypes are also called blueprints (as in the architectural drawings familiar to most of us), or sunprints. In 1842, the British chemist and astronomer Sir John Herschel discovered the process, and it was immediately embraced by both professional artists and amateurs. Because of its ability to capture dark shadows and highlights, early uses included documenting botanical specimens, such as the work by Worcester native Frederick Coulson and the English botanist Anna Atkins, whose Honey Locust Leaf & Pod (1854) is included in the show. Other images I found striking were Arthur Wesley Dow‘s Two Vases with Irises (1900) and the anonymous Lace Samples (1905).

Cyanotypes were also used extensively to document travels; I was intrigued by the Worcester scenes (1890) by Stephen C Earle, Mississippi River scenes (1885-1891) by Henry Boss, and Albert Lévy‘s photographs of the 1900 Paris Exposition. Another photographer who used this method was Eugene de Salignac, who during the years 1906-1934 also made more than 20,000 glass plate negatives of New York City structures.

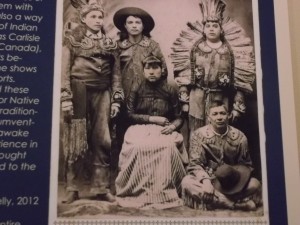

Although the human figure was not considered a fitting subject for these types of photographs, the show includes some beautiful photographs of people, which, although they have blue skin, are not as unsettling as you might think. I especially liked Edward Sheriff Curtis‘ portrait of the Native American Spidis Wisham (1905) and the two “body slices” (1940) which were used in anatomy classes.

After World War I, the popularity of cyanotypes waned swiftly, but beginning in the 1970s, contemporary artists rediscovered its potential. I appreciated seeing a number of the modern pieces, starting with Barbara Kasten‘s Untitled 75/31 (1975), and including such pieces as Marco Breuer‘s Untitled E-33 (2005), Christian Marclay‘s Unwound Cassette Tape (2012), and finally the Annie Lopez dress Medical Conditions (2013).

Around 5 pm, I made my way to the Mary Cosgrove Dolphin Gallery on the first floor of the Ghosh Science and Technology Center at Worcester State. Tonight was the opening reception for the 2016 Student Thesis Art Exhibit, in which nine WSU students graduating with a degree in Visual and Performing Arts display their best work; the exhibit closes on May 13. It certainly is a mixed bag: costume design, sculpture, photography, painting in oils and acrylics, paper cutouts, collage, and more, in both abstract and realistic styles. I think my favorite was the illustrated children’s book Busy Beetle’s Traveling Trading Post by Aislyn Cole. Best of luck to these talented graduates!