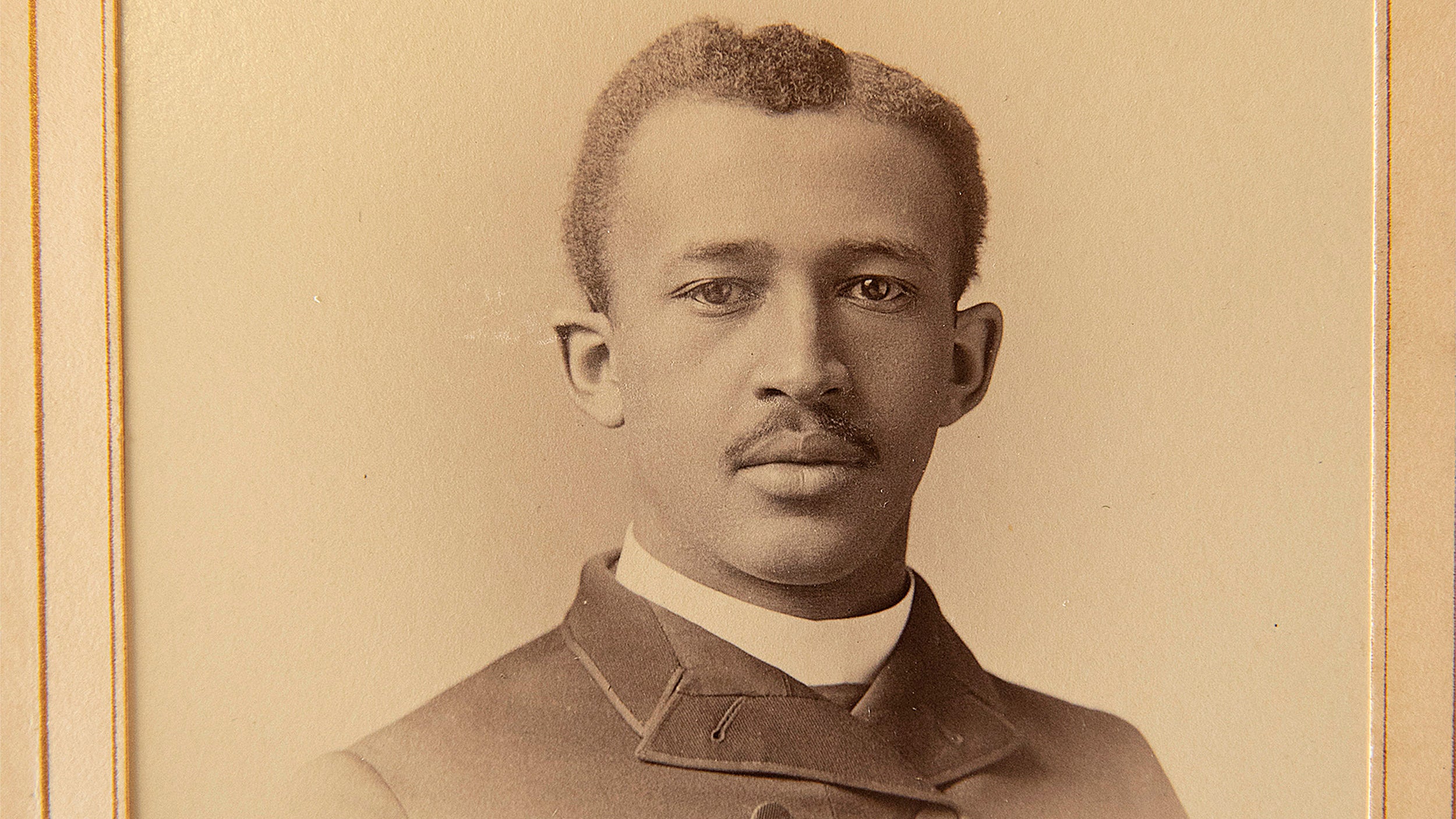

The Emergence of a Protest Narrative in W.E.B. Du Bois’ “Of the Training of Black Men”

Throughout this course, protest narratives have surfaced in a multitude of ways, whether it is the alternative stories presented in the writings of indigenous authors like Sarah Winnemucca or in the argument against white supremacy as portrayed in Charles Chesnutt’s The Marrow of Tradition. A key difference between the writings of Chesnutt and Winnemucca is that the former crafted a story that could be read as a story of protest against social injustices, whereas Life among the Paiutes was a protest narrative simply because it existed in the first place. Winnemucca was engaging in a protest because she was telling an alternative story of history, en route to eliminating the single story. W.E.B. Du Bois’s writing in The Souls of Black Folk diverges from this iteration of a protest narrative in the sense that the book is comprised of essays that contain arguments for true justice and equality for African-Americans. One essay in particular, “Of the Training of Black Men,” features Du Bois protesting against the plan for a southern, industrial education for freed black men as he supplements this with a rhetorical argument for black men to receive a holistic education.

Expanding on the arguments made by Du Bois in The Souls of Black Folk is writer Ellicott Wright in his article, “The Souls of Black Folk and My Larger Education.” Throughout this article, Wright compares Du Bois’s book to My Larger Education, a novel by Booker T. Washington. He details the naive hypocrisy with which Washington advocated for black men to receive industrial educations and the rebuke of Washington as scribed by Du Bois in his essay, “Of Mr. Booker T. Washington and Others,” as well as his protest against the industrial education system to which African-American men were relegated in The Souls of Black Folk, as a whole, and especially in, “Of the Training of Black Men.” In addition to the similarities and differences drawn by Wright, he also posits that, in regards to the conflict between the two writers over Southern industrial education, Du Bois’ “logical and intelligent approach did not fulfill the immediate problems of the millions of suffering Negroes in the South, but his overall vision…gave him the ability to select and reject from among the methods Washington was using” (Wright 442). Essentially, Wright’s claim about Du Bois’ attitude towards Southern industrial education as it manifested in The Souls of Black Folk is that “He did not like to see Negroes blaming themselves for their unfortunate position…Du Bois…wished to lead the Negro upward from above” (Wright 442-443).

This argument presented by Wright is a sound one in the sense that Du Bois wrote as a form of leadership for black men of the moment to deliver them loftier and more noble ambitions than they might otherwise have deemed themselves worthy of, but a significant contention of Wright’s argument is that Du Bois was not providing an instantaneous solution for black people in the South who were struggling. While it is true that Du Bois was not providing a solution for the struggle on a day-to-day basis, he was providing the answer for African-Americans going forward. His vision was both general and direct in the sense that if African-Americans were to read “Of the Training of Black Men,” they would understand the flaws of the Southern industrial education system and work to achieve an education that would allow them to better understand themselves. This, too, can be a means of minute to minute survival.

In his essay, Du Bois criticizes the colleges that were established for black men who were recently freed from the confines of slavery as “hurriedly founded, inadequately equipped, illogically distributed, and of varying efficiency and grade” (Du Bois 58). Even more than outright, physical difficulties with these institutions, Du Bois also criticized the ideology behind them because he knew the colleges and their curriculums were not the answer to the struggles of African-Americans in the South. Instead, he saw this educational solution as one that would “best use the labor of all men without enslaving or brutalizing; such training as will give us poise to encourage the prejudices that bulwark society” (Du Bois 57). Du Bois does expand on this idyllic notion later in the essay, but he initially begins his protest against the Southern industrial education system with a stern condemnation of it.

The biggest element that Du Bois took issue with was the manner in which the United States attempted to rush the integration of African-Americans into society after the abolition of slavery. Of course, Du Bois critiqued the aforementioned notion that the colleges were rushed, but he also criticized the curriculum. His protest did not only come from the fact that African-Americans were receiving an industrial education because the Southern governments believed that was the only type of education they were capable of internalizing, but also from the fact that black men were never given the opportunity to prove themselves worthy of greater societal integration. Du Bois believed that African-Americans were generally ignorant of how to function in a proper society and his protest stemmed from the notion that if black men were given the necessary educational opportunities on how to be functioning members of a society, they would embrace a larger swath of societal capabilities beyond the workforce and hard labor. However, the opportunities were simply never afforded in the first place and Du Bois protested against the scarcity of these Southern colleges, as well as the spread of racism that they encouraged. It stands to reason then why Du Bois’ argument would be largely centered around the notion that the panacea for Southern education would exist not only as a means for opportunity, but also as a method for quelling racist sentiment.

Du Bois buoys his protest with a concession that industrial education does have its own merits, but it cannot properly exist on its own without also being supplemented by a more liberal education, as well. Essentially, Du Bois was opposed to one-dimensional methods of education. He takes the extra step in this protest by feeling it unfortunately necessary to provide statistical evidence for why black men deserve an education that reaches further than industrial training, in case of opposing arguments in line with the aforementioned racist sentiment that black men are inherently inferior and therefore undeserving of a proper education. In his protest in favor of expanded education for black men, Du Bois writes, “From such schools about two thousand Negroes have gone forth with the bachelor’s degree. The number in itself is enough to put at rest the argument that too large a proportion of Negroes are receiving higher training” (Du Bois 62). Du Bois thoroughly believed, through both anecdotes and statistics, that African-Americans were, of course, deserving of higher levels of education and his advocation for them does not constitute an immediate solution for the struggle of African-Americans in the South, but the encouragement and the leadership he exhibits in his protest of those who would oppose the idea that black men should reach higher and further is reason enough to rebuke Wright’s claim that Du Bois operated merely within a larger, overarching narrative of black liberation.

This is not to say that Du Bois never engaged in this sort of protest, either. In fact, much of Du Bois’ writing in this particular essay (following his protest of the Southern industrial education system and the opponents of any alternative for African-Americans) expands on his idyllic hopes for the future of black education. He writes, “We have a right to inquire…if after all the industrial school is the final and sufficient answer in the training of the Negro race: and to ask gently, but in all sincerity…Is not life more than meat, and the body more than raiment?” (Du Bois 58). While this exists more as a notion of protest in favor of black men experiencing true life that is owed to them, he does continue to lay out his belief for what sort of education should be provided to black men when he writes, “it must maintain the standards of popular education, it must seek the social regeneration of the Negro, and it must help in the solution of problems of race contact and cooperation. And finally, beyond all this, it must develop men” (Du Bois 66). In addition to advocating for higher education for African-Americans, Du Bois is also protesting for the idea that black men can be contributing members of society, if only they are given the chance.

Du Bois believes, as evidenced by the above quotes, that the primary goal of the African-American at that moment was to understand himself and he believed that proper collegiate institutions were the solution to this ambition. As he concludes his essay, Du Bois does not only protest against the failings of the Southern industrial education, but he is also protesting against the American education system as a whole due to the fact that the government, at the time, was content to let African-Americans grow miserable as a result of the education they were receiving. But the Southern industrial educations only allowed for black men to experience growing discomfort and a palpable sense of repression that emphasized daily that while they were no longer slaves, they were also not at all free.

Du Bois protested against the entire educational system that was put into place for African-Americans after slavery was abolished because he believed that the creation of educational opportunities was the only mechanism by which black men could come to better understand themselves and their roles as functioning and contributing members of society. To deny African-Americans these opportunities was nothing more than to keep them in bondage, albeit a different type of bondage in a post-slavery America, but a repressive, suffering bondage nonetheless. While Du Bois was not necessarily on the front lines of legislation and education reform during his time, his leadership was unequivocally necessary. And an immediate impact on black men who were still developing their own senses of identity could be tangible in any struggling African-American who might have read “Of the Training of Black Men” in The Souls of Black Folk.

Works Cited

Du Bois, W.E.B. The Souls of Black Folk. Dover Publications, 1994.

Wright, Ellicott. “The Souls of Black Folk and My Larger Education.” The Journal of Negro

Education, vol. 30, no. 4, 1961, pp. 440–444.

Image Source: Harvard Gazette