We ran a survey previously conducted by Brian Smith four times, to test our techniques against a gold-standard data set.

| Date launched |

Time of Day launched (EST) |

Total

Responses |

Unique

Respondents |

Breakoff? |

| Tue Sep 17 2013 |

Morning 9:53:35 AM EST |

43 |

38 |

No |

| Fri Nov 15 2013 |

Night |

90 |

67 |

Yes |

| Fri Jan 10 2013 |

Morning |

148 |

129 |

Yes |

| Thu Mar 13 2014 |

Night 11:49:18 PM EST |

157 |

157 |

Yes |

This survey consists of three blocks. The first block asks demographic questions : age and whether the respondent is a native speaker of English. The second block contains 96 Likert-scale questions. The final block consists of one freetext question, asking the respondent to provide any feedback they might have about the survey.

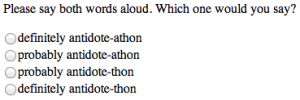

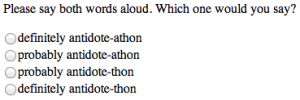

Each of the 96 questions in the second block asks the respondent to read aloud an English word suffixed with either of the pairs “-thon/-athon” or “licious/-alicious” and judge which sounds more like an English word.

First Run

The first time we ran the survey was early in SurveyMan’s development. We had not yet devised a way to measure breakoff and had no quality control mechanisms. Question and option position were not returned We sent the data we collected to Joe Pater and Brian Smith. Brian reported back :

The results don’t look amazing, but this is also not much data compared to the last experiment. This one contains six items for each group, and only 26 speakers (cf. to 107 speakers and 10 items for each group in the Language paper).

Also, these distributions are *much* closer to 50-50 than the older results were. The fact that -athon is only getting 60% in the final-stress context is kind of shocking, given that it gets 90% schwa in my last experiment and the corpus data. Some good news though — the finding that schwa is more likely in -(a)thon than -(a)licious is repeated in the MTurk data.

Recall that the predictions of the Language-wide Constraints Hypothesis are that:

1. final stress (Final) should be greater than non-final stress (noFinal), for all contexts. This prediction looks like it obtains here.

2. noRR should be greater than RR for -(a)licious, but not -(a)thon. Less great here. We find an effect for -thon, and a weaker effect for -licious.

licious (proportion schwaful)

noRR RR

Final 0.5276074 0.5182927

noFinal 0.4887218 0.5031056

thon (proportion schwaful)

noRR RR

Final 0.5950920 0.5670732

noFinal 0.5522388 0.4938272

Our colleagues felt that this made a strong case for automating some quality control.

Second Run

The second time we ran this experiment, we permitted breakoff and used a Mechanical Turk qualification to screen respondents. We required that respondents have completed at least one HIT and have an approval rate of at least 80% (this is actually quite a low approval rate by AMT standards). We asked respondents to refrain from accepting this HIT twice, but did not reject their work if they did so. Although we could have used qualifications to screen respondents on the basis of country, we instead permitted non-native speakers to answer, and then screened them from our analysis. In future versions, we would recommend making the native speaker question a branch question instead.

We performed three types of analyses on this second run of the survey : we filtered suspected bots, we flagged breakoff questions and positions, and we did correlation analysis.

Of the 67 unique respondents in this second run of the phonology survey, we had 46 self-reported native English speakers. We flagged 3 respondents as bad actors. Since we do not have full randomization for Likert scale questions, we use positional preference to flag potential adversaries. Since symmetric positions are equally likely to hold one extreme or another, we say that we expect the number of responses in either of the symmetric positions to be equal. If there is a disproportionate number of responses in a particular position, we consider this bad behavior and will flag it. Note that this method does not address random respondents.

Our three flagged respondents had the following positional frequencies (compared with the expected number, used as our classification threshold). The total answered are out of the 96 questions that comprise the core of the study.

| Position 1 |

Position 2 |

Position 3 |

Position 4 |

Total Answered |

| 82 >= 57.829081 |

4 |

10 |

0 |

96 |

| 0 |

84 >= 64.422350 |

9 |

3 |

96 |

| 28 >= 24.508119 |

10 |

0 |

1 |

39 |

We calculated statistically significant breakoff for both question and position at counts above 1. We use the bootstrap to calculate confidence intervals and round the counts up to the nearest whole number. Due to the small sample size in comparison with the survey length, these particular results should be viewed cautiously:

| Position |

Count |

| 40 |

2 |

| 44 |

2 |

| 49 |

3 |

| 66 |

2 |

| 97 |

20 |

Wording Instance

(Question) |

Suffix |

Count |

| ‘marine’ |

‘thon’ |

2 |

| ‘china’ |

‘thon’ |

2 |

| ‘drama’ |

‘thon’ |

2

| |

| ‘estate’ |

‘thon’ |

2 |

| ‘antidote’ |

‘thon’ |

4 |

| ‘office’ |

‘licious’ |

2 |

| ‘eleven’ |

‘thon’ |

2 |

‘affidavit’ |

‘licious’ |

2 |

Two features jump out at us for the positional breakoff table. We clearly have significant breakoff at question 98 (index 97). Recall that we have 96 questions in the central block, two questions in the first block, and one question in the last block. Clearly a large number of people are submitting responses without feedback. The other feature we’d like to note is how there is some clustering in the 40s – this might indicate that there is a subpopulation who does not want to risk nonpayment due to our pricing scheme and has determined that breakoff is optimal at this point. Since we do not advertise the number of questions or the amount we will pay for bonuses, respondents must decide whether the risk of not knowing the level of compensation is worth continuing.

Like Cramer’s $$V$$, we flag cases where Spearman’s $$\rho$$ are greater than 0.5. We do not typically have sufficient data to perform hypothesis testing on whether or not there is a correlation, so we flag all found strong correlations.

The correlation results from this run of the survey were not good. We had 6 schwa-final words and 6 vowel-final words. There are 15 unique comparisons for each set. Only 5 pairs of schwa-final words and 3 pairs of vowel-final were found to be correlated in the -thon responses. 9 pairs of schwa-final words and 1 pair of vowel-final words were found to be correlated in the -licious responses. If we raised the correlation threshold to 0.7, none of the schwa-final pairs were flagged and only 1 of the vowel-final pairs was flagged in each case. Seven additional pairs were flagged as correlated for -thon and 3 additional pairs were flagged for -licious.

Third Run

The third run of the survey used no qualifications. We had hoped to attract bots with this run of the survey. Recall that in the previous survey we filtered respondents using AMT Qualifications. Our hypothesis was that bots would submit results immediately.

This run of the survey was the first in this series to be launched during the work day (EST). We obtained 148 total responses, of which 129 were unique. 113 unique respondents claimed to be native English speakers. Of these, we classified 8 as bad actors.

| Position 1 |

Position 2 |

Position 3 |

Position 4 |

Total Answered |

| 23 >= 21.104563 |

41 |

31 |

1 |

96 |

| 0 |

3 |

51 >= 40.656844 |

38 >= 30.456324 |

92 |

| 25 >= 22.476329 |

39 |

31 |

1 |

96 |

|

29 |

67 >= 66.209126 |

|

96 |

| 6 |

12 |

43 >= 41.282716 |

21 |

82 |

| 0 |

4 |

42 >= 35.604696 |

50 >= 38.141304 |

96 |

| 6 |

28 |

32 |

30 >= 29.150767 |

96 |

| 25 |

0 |

3 |

68 >= 64.422350 |

96 |

Clearly there are some responses that are just barely past the threshold for adversary detection ; the classification scheme we use is conservative.

Interestingly, we did not get the behavior we were courting for breakoff. Only the penultimate index had statistically significant breakoff; 51 respondents did not provide written feedback. We found 9 words with statistically significant breakoff at abandonment counts greater than 2 (they all had counts of 3 or 4). The only words to overlap with the previous run were “estate” and “antidote”. The endings for both words differed between runs.

As in the previous run, only 5 pairs of schwa-final words plus -thon had correlations above 0.5. Fewer vowel-final pairs (2, as opposed to 3) plus -thon were considered correlated. For the -licious suffix, 10 out of 15 pairs of schwa-final words had significant correlation, compared with 9 out of 15 in the previous run. As in the previous run, only 1 pair of vowel-final words plus -licious had a correlation coefficient above 0.5. This results do not differ considerably from the previous run.

Fourth Run

This run was executed close to midnight EST on a Friday. Of the 157 respondents, 98 reported being native English speakers. We found 83 responses that were not classified as adversaries. Below are the 15 bad actors’ responses:

| Position 1 |

Position 2 |

Position 3 |

Position 4 |

Total Answered |

| 65 >= 64.422350 |

3 |

0 |

28 |

96 |

| 29 >= 25.847473 |

2 |

0 |

2 |

33 |

| 0 |

5 |

87 >= 63.825733 |

4 |

96 |

| 9 |

18 |

19 |

37 >= 35.604696 |

83 |

| 13 |

2 |

18 |

52 >= 47.483392 |

85 |

| 53 >= 40.029801 |

2 |

1 |

0 |

56 |

| 96 >= 66.209126 |

|

|

0 |

96 |

| 3 |

12 |

40 >= 39.401554 |

41 >= 34.327636 |

96 |

| 1 |

3 |

5 |

17 >= 16.884783 |

26 |

| 3 |

1 |

1 |

91 >= 65.018449 |

96 |

| 36 >= 33.044204 |

42 >= 40.656844 |

12 |

6 |

96 |

| 6 |

32 >= 29.804578 |

5 |

0 |

43 |

| 35 >= 30.456324 |

41 |

17 |

3 |

96 |

| 20 >= 19.716955 |

18 |

11 |

2 |

51 |

| 0 |

0 |

5 |

91 >= 63.228589 |

96 |

For the -thon pairs, 1 out of the 15 schwa correlations was correctly detected. None of the vowel correlations correctly were detected. For -licious, 2 schwa pair correlations were correctly detected and 4 vowel pair correlations where correctly detected.

For this survey we calculated statistically significant breakoff for individual questions when their counts were above 2 and for positions when their counts were above 1. The penultimate question had 38 instances of breakoff. Fourteen questions had breakoff. The maximum cases were 4 counts each for “cayenne” and “hero” for the suffix -licious.

Entropy Comparison

We observed the following entropies over the 96 questions of interest. Note that the maximum entropy for this section of the survey is 192.

| Instance |

Initial Entropy |

Entropy after

removing adversaries |

| Fourth Run |

186.51791933021704 |

183.64368029571745 |

| Third Run |

173.14288208850118 |

169.58411284759356 |

| Second Run |

172.68764654915321 |

169.15343722609836 |

Notes

Due to a bug in the initial analysis in the last survey (we changed formats between the third and the fourth), the first run of the analysis did not filter out any non-native English speakers and ran the analysis on 137 respondents. There were 20 adversaries calculated in total and only a handful of correlations detected. The entropy before filtering was 190.0 and after, 188.0. We also counted higher thresholds for breakoff. We believe this illustrates the impact of a few bad actors on the whole analysis.

Note that we compute breakoff using the last question answered. A respondent cannot submit results without selecting some option; without doing this, the “Submit Early” button generally will not appear. However, for the first three runs of the survey, we supplied custom Javascript to allow users to submit without writing in the the text box for the last question.