Where does the runtime fit in?

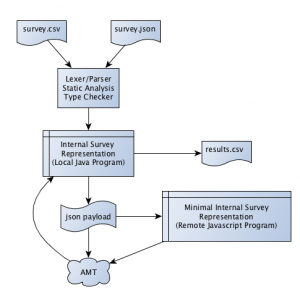

A SurveyMan workflow looks something like this :

We currently only support csv input; the design of the csv language is such that a human could reasonably write a survey in it. Molly is currently working on a Python library that will streamline some of the more advanced features of SurveyMan and Python proficient users to design surveys in Python and output a JSON equivalent to a csv survey.

The main SurveyMan program is written in Java. It handles all of the static checks on the input and loads the survey into an internal representation. When it is time to send the program to a crowdsourcing platform, the Java program produces a minimal JSON representation of the survey and sends this wrapped in HTML. When the crowd platform is Mechanical Turk, the HTML is sent inside an XML payload and handled by AMT. When the platform is a local server, it just sends the HTML. We can support any crowdsourcing platform that allows us to send arbitrary HTML.

We send the minimal JSON representation for two reasons. The first is that for AMT, we have a maximum payload allowed. The second reason is because not all of the survey data is useful to the runtime. We need sufficient information to determine how to display the survey to the user. We don’t do any analysis on the crowdsourcing platform, so we don’t need to send over information like the CORRELATED column or any user-provided columns. We do allow survey designers to add custom Javascript to their survey, which can be used to perform computations and return the results of those computations.

Input

The input to the SurveyMan program is a survey csv. This csv is parsed and loaded into an internal representation, which is then translated into a JSON payload. The resulting JSON representation of the survey is sent to the crowdsourcing platform. This survey JSON is then interpreted by a Javascript program that controls flow through the survey and how individual questions are displayed.

The Finite State Machine

SurveyMan surveys are interpreted in Javascript on a finite state machine that controls the underlying evaluation and display.

There are two layers to the survey interpreter. The first handles survey logic; it essentially runs in a loop, proffering questions and consuming responses. The second layer handles display information, updating the HTML in response to certain events.

User’s view of the FSM

A respondent navigates to the webpage displaying the survey. For AMT, we show a consent form in the HIT preview. When an individual accepts a HIT, they begin a survey. The consent form mechanism is not currently implemented in the local server.

The user then sees the first question* and the answer options. When they select some answer (or type in a text box), the next button and a “Submit Early” button appear. If the question is instructional and is not the final question in the survey, only the next button appears. When the respondent reaches the final question, only a

Each user sees a different ordering of questions. However, a single user’s questions are presented in the same order; the random number generator is seeded with the user’s session or “assignment” id. In AMT, this means that if the user navigates away from the page and returns to the HIT, the question order will be the same upon second viewing.

Only one question is displayed at a time. This design decision is not purely aesthetic; it helps us measure breakoff.

Underlying machinery

In addition to the functions that implement the state machine, there are three other underlying data structures:

- Block Stack : Since our path through the survey is determined by branching over blocks, and since we may only branch forward, we keep the top-level blocks on a stack.

- Question Stack : Once we know which block we’re to execute, we can fetch the appropriate questions for that block.

- Branch Reference Cell : The branch target is stored here, since we defer executing any branching at least until all of the questions in the block have been seen.

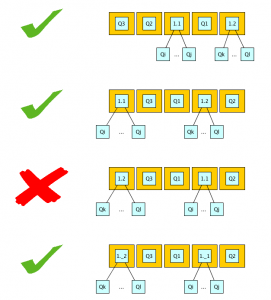

The SurveyMan interpreter is initialized as follows : the survey JSON is parsed into an internal survey representation and then randomized using a seeded random number generator. This randomization preserves necessary invariants (e.g. the partial order over blocks). We then push the top level blocks onto the block stack. Then we pop off the first block and initialize the question stack using getAllQuestions.

The interpreter’s execution runs as follows :

procedure run

begin

while blockStack is not empty

do

question <- getNextQuestion()

display question and answer options

answer <- user-provided answer

store answer

if the question is a branch question

then

branchRef <- answer's branch destination

fi

if user selects submit

then

return stored answers

fi

done

return stored answers

end

Answers are stored in the HTML forms in the usual way. We have three main divs in the HTML : one for the displayed question, one for the displayed answers, and one for response input data. The response input elements are kept in a hidden div below the answer display div. Each new response is inserted above the previous one, emulating a stack.

The function getNextQuestion handles control flow and is the primary point of interaction with the FSM:

function getNextQuestion

output : question

begin

if questionStack is empty

if branchRef is set

then

while true

do

nextBlock <- peek(blockStack)

if nextBlock = branchRef

then

questionStack <- getAllQuestions(pop(blockStack))

unset branchRef

break

else if nextBlock is a floating block

then

questionStack <- getAllQuestions(pop(blockStack))

break

else

pop(blockStack)

fi

done

else

questionStack <- getAllQuestions(pop(blockStack))

fi

return pop(questionStack)

end

Determinism in the runtime

There are two main sources of nondeterminism in SurveyMan. The first is our random number generator; the second is human behavior.

We had previously generated a new static HTML version of the survey for each respondent. Each question was contained in its own div and branch destinations pointed to these divs. None of the blocking structure was visible to the user. The Javascript was minimal; if the question was a branch, it would hide the current question and display the the div with the appropriate id. If the question did not have branching, it would navigate the DOM and just display the next div.

This prior approach lead to a technical issue that proved to be a nice metaphor for the underlying system. The problem was that, since we had to send over unique HTML for every desired respondent, we ended up with many HITs posted on AMT. AMT groups together HITs that have similar parameters and facilitates workers’ acceptance of consecutive HITs in groups. Having many HITs not only attracted bad actors, but it also annoyed honest respondents, who did not always realize that they were not supposed to answer all of the HITs.

While each respondent sees a different version of the survey, the underlying survey is essentially “the same.” It made more sense to move the survey logic into the Javascript and post a single HIT. It was also cleaner to group together user behavior with survey execution, rather than flattening the survey and adding an extra (albeit simpler) evaluator that primarily responded to user nondeterminism.

What’s key about these two approaches is that the two types of nondeterminism are quite different from each other. Randomization gives us predictable behavior in the limit and, depending upon the task may not even have an impact on the computation. Randomization does not occur in response to user behavior and can be done before executing anything. Once we know which block to execute, the total set of questions is almost deterministic. That is, rather than having to account for nondeterminism and uncertainty at every step in the evaluation, we only have to handle it at known junctures. So long as we can prove that the set of surveys produced at each junction are equivalent, we know that the evaluation is sound.

* The respondent may also see a breakoff notice first. This is just a page stating that they may submit results at any time and that they will be paid bonuses commensurate on the number and quality of questions answered. It can be turned off.