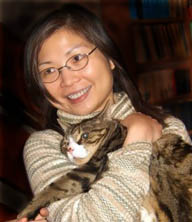

Guest blogger Man Yee Kan, Department of Sociology, University of Oxford, pictured here with her cat Sammie, writes:

I came to Oxford from Hong Kong eight years ago as a sociology graduate student and soon after that met my partner Timothy, a philosopher who is also from Hong Kong. Our favourite hobby in Oxford is to visit cats near the canal and in colleges. We treat our cat Sammie like a son.

Why not have a ‘real’ child? We can’t afford it! Our parents are in Hong Kong and cannot come to help out. Private childcare in the UK is too expensive for us. In addition, our parents need our care. In Hong Kong, as in many Asian societies, adult children are expected to provide both financial support and personal care to elderly parents. This responsibility shapes public policies. For example, when we worked in Hong Kong, we received a parental care tax allowance.

My empirical contribution to the GeNet project examines changes in the time use of men and women over the life course and their implications for labour market earnings. Findings show that in the United Kingdom many women quit labour market work or change to part-time jobs after having a child. Accordingly, they increase their time spent on routine housework (e.g. cooking, cleaning, washing the dishes and doing the laundry) and family care and reduce the time on consumption and leisure. Men, on the other hand, tend to stay with full time jobs after having a child. Their routine housework time changes little, although time spent on childcare and non-routine types of housework (e.g. grocery shopping and household repairs) increases significantly (by about 80 minutes per day) after having a child.

Timothy is a good cat carer, so I think he would also undertake a lot of childcare if we had a child. In academic papers, housework hours of husbands and wives are often explained by simple bargaining models, where higher income relative to one’s partner predicts shorter housework hours. In reality, housework and care are intricately intertwined with power, love and feelings of identity.

Some scholars describe career women like me, who have opted for having a cat instead of having a child, as “work-centred” rather than “home-centred.” But my preferences seem to be affected by my environment. When I’m unhappy about my job, I’m more likely to dream about having a baby, and who knows how I’ll feel a year or five years from now… Meanwhile, I’m enjoying Sammie.