Guest post by Barbara E. Hopkins, Wright State University.

Guest post by Barbara E. Hopkins, Wright State University.

The Chinese Communist Party has officially abandoned the “one-child” policy and now allows all married couples to have two children. However welcome this policy shift, it is unlikely to fend off the worsening care crisis associated with an aging population. The New York Times reports that only 12% of eligible couples responded to a recent relaxation of the rules. In urban areas of China, in particular, many families consider a second child prohibitively expensive.

The Party remains concerned about a shrinking workforce. Any given productivity level will yield a lower GDP per capita when a smaller percentage of the workforce is of working age. Although China’s natural rate of population growth is .5% per year, new workers are not replacing aging workers. While the share of the total population over 65 is one-half that of Denmark, the size of the elderly relative to the working age population has increased from 8% to 13% in the last 35 years.

Denmark has more policy options than China. Because a large percentage of its workers are in white-collar jobs, it may be easier to persuade them to postpone retirement longer. In contrast, a significant share of the Chinese labor force engages in physically demanding manual labor that elderly workers may not be able to sustain. Denmark can encourage immigration from low-wage countries like Syria to meet some of its labor needs. In contrast, the Chinese population is probably too large to rely on migration. Further, net outmigration is significant, especially among educated workers. China has a brain drain problem.

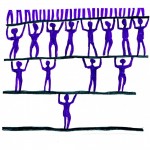

While the Party is focused on the negative implications of further fertility decline for economic growth, implications for elder care are even more problematic. In a one-child system, each child is the only child of two parents. Each woman is likely to be the only daughter or daughter-in-law of four parents and eight grandparents. This adds up to a huge burden for working women who are expected to provide care.

According to the International Labor Organization, the number of older persons living with their children in China has declined from 73% in 1982 to 57% in 2005. The exact scope of the problem is difficult to measure, because the costs of caring for parents are even more difficult to estimate than the costs of caring for children. But they are substantial. (Rachel Connelly and Margaret Maurer-Fazio describe this problem in more detail).

The needs of aging parents are not as predictable as the needs of children, since the range of disability for any given age varies considerably from person to person. Improved medical care can both increase and decrease the need for care, by increasing an older person’s functionality or by increasing life expectancy. Children of the largest age cohort in China—people in their forties and fifties—are about to age into new responsibilities for elder care.

The gender division of labor that assigns care work to women raises additional problems for China’s demographic trends. In addition to declining birthrates, China also suffers from a sex-selection problem. The number of females under 20 is only 86% of the number of males. Chinese demographers are concerned. They worry that men unable to find a mate will turn violent.

While policies and norms encouraging son preference are weakening, the most recent population data shows the smallest share of girls relative to boys in the youngest cohort. Gender norms that assign care responsibilities to women, may, as some assert, encourage different thinking about son preference, but these changes will come too late to solve the impending care crisis.

That young couples are finding it too costly to take on the responsibility of more children means either that people are less willing to take responsibility for caring for others relative to other uses of their time and money or that the costs of care are greater than they used to be, or both.

The working age population may also find obligations toward their parents increasingly burdensome. The younger generation’s rush toward cities (or foreign countries) in search of employment has often increased their physically separation from both children and the elderly.

The International Labour Office assumes that 4.2 long-term care workers are needed per 100 persons over age 65. According to their projections, more than 70% of the over-age 65 population may prove vulnerable to a care deficit.

Posted January 14, 2016