This week I asked you to reflect on how the digital tools that we have at our hands is transforming the way that historians go about their business (or research). There have been many advances in technology that have allowed historians to explore new geographic areas, new methods of research, and manipulate data in new and inventive ways. The other week, I showed some examples of a new digital tool being developed by IBM’s research lab in Cambridge – ManyEyes. If you didn’t have a chance to check it out after class, I encourage you to still take a look. Here is a good example of several different ways in which ManyEyes can visualize data in a way that had not really been available to average historians without access to very powerful computing power.

This election cycle is also producing some interesting digital tools that might be of interest for present and future historians. One is an adaptation of the visualization that we find at ManyEyes and is a visualization of how people are feeling on election day. At the New York Times, you can enter in key words about how you are feeling and add it to the data pool being collected by contributions from others around the world. You can visualize the results generically or separate out the McCain and Obama supporters. Over at the Washington Post you can track Twitter, video, and news postings that are referenced by place and time. This visualization is rather interesting because you can move the slidebar and see how coverage in different areas changes over time.

Other interesting digital tools that have been created for historians are not yet commercially available, but the technology behind them and the potential uses by historians now and in the future are significant. One of my favorite tech developments has been going on in Germany (surprise!). On the eve of the communist party’s fall from power, the secret police (the Stasi) began shredding documents (amounting to some 16,000 sacks of shredded paper). The people at the Frauenhofer Institut, the same people who brought you the MP3) have been working on a digital solution. Funded by the German federal government and working closely with the archivists at the Stasi Archive, the technicians have been working on software that can match together the shredded and torn pieces of paper to reconstruct the original document. It is estimated that if 30 people were tasked with this job, it would take somewhere between 600 and 800 years! You can read more about this story here and here.

Other interesting digital tools that have been created for historians are not yet commercially available, but the technology behind them and the potential uses by historians now and in the future are significant. One of my favorite tech developments has been going on in Germany (surprise!). On the eve of the communist party’s fall from power, the secret police (the Stasi) began shredding documents (amounting to some 16,000 sacks of shredded paper). The people at the Frauenhofer Institut, the same people who brought you the MP3) have been working on a digital solution. Funded by the German federal government and working closely with the archivists at the Stasi Archive, the technicians have been working on software that can match together the shredded and torn pieces of paper to reconstruct the original document. It is estimated that if 30 people were tasked with this job, it would take somewhere between 600 and 800 years! You can read more about this story here and here.

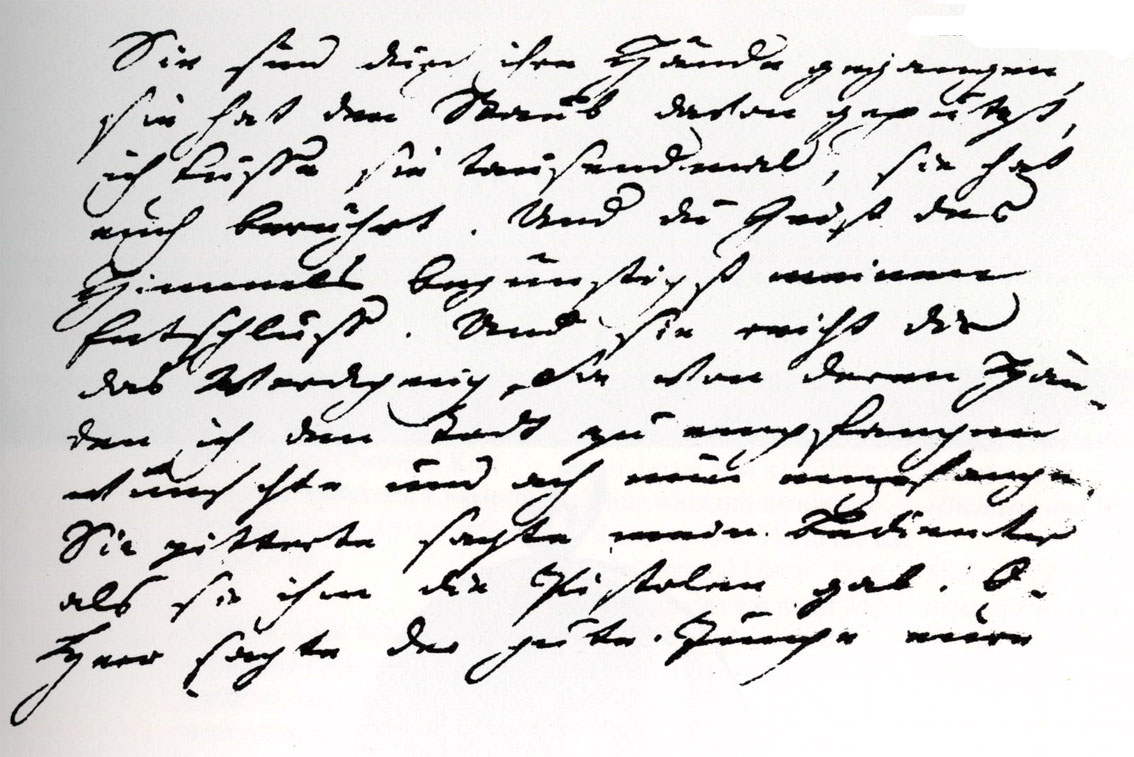

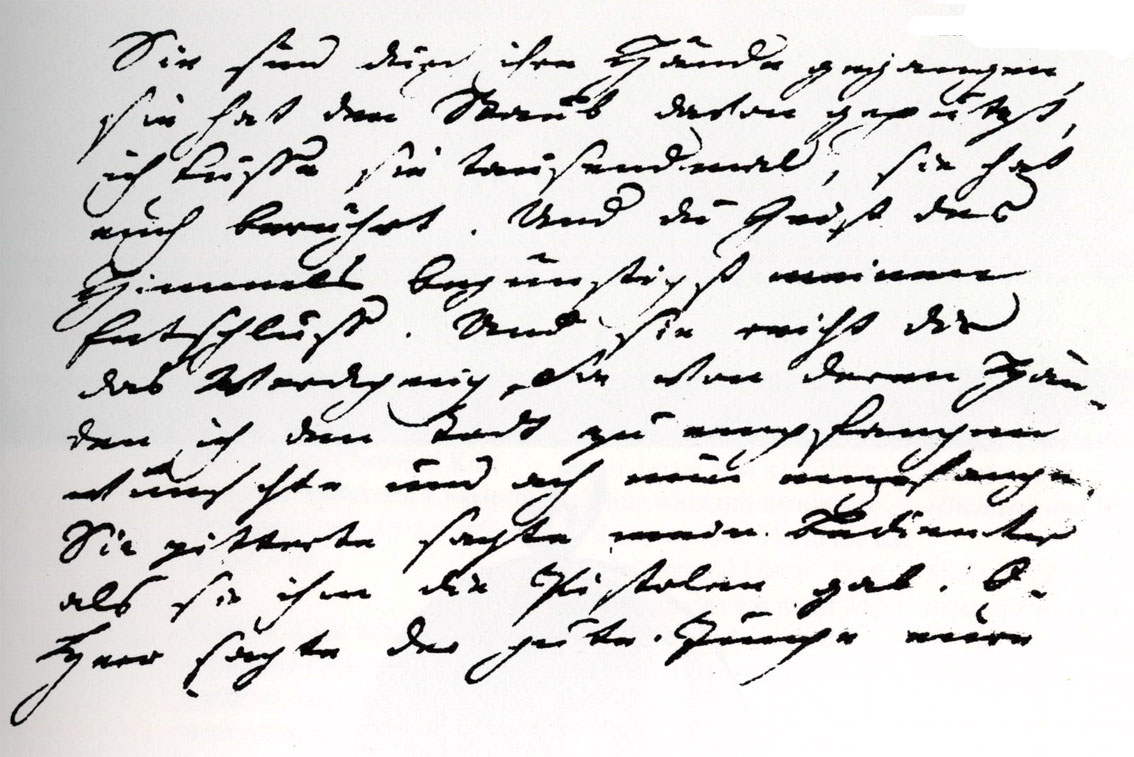

The other project that I am excited about was developed right here at UMass! Working with a set of letters from George Washington, the Center for Intelligent Information Retrieval developed software that can learn how Washington wrote and translate this into data, which in turn can be searched and manipulated. For many of us who have to deal with handwriting manuscripts (luckily most of my sources are typed, but there is a certain degree of marginalia involved as well as occasional handwritten items) being able to scan, store, and manipulate such documents will be a great leap forward. Just take a look at the sample of late 18th century German handwriting (Goethe’s manuscript of Werther) on the left to see how difficult such sources can be to work with.

The other project that I am excited about was developed right here at UMass! Working with a set of letters from George Washington, the Center for Intelligent Information Retrieval developed software that can learn how Washington wrote and translate this into data, which in turn can be searched and manipulated. For many of us who have to deal with handwriting manuscripts (luckily most of my sources are typed, but there is a certain degree of marginalia involved as well as occasional handwritten items) being able to scan, store, and manipulate such documents will be a great leap forward. Just take a look at the sample of late 18th century German handwriting (Goethe’s manuscript of Werther) on the left to see how difficult such sources can be to work with.

Speech recognition remains the Holy Grail of the digital historian. Back in 1998 or 1999 (I can’t remember exactly when this was) I attended a German-American young-leaders conference and had been assigned the job of introducing one of our keynote speakers, Walter Isaacson, who was the Editor of Time at the time. We had arranged to have breakfast together so that I could go over a few things with him and I was just making small talk when I asked him what he was currently working on. He responded that he had just gotten back from a week-long visit to Microsoft for a series they were working on about the next generation operating system (what would become XP). He was visiting their voice recognition lab and he noticed a banner hanging on the wall that read – “Wreck a Nice Beach!” He asked “Bill” what the sign was for – the response was that the unit can takedown the banner when saying “recognize speech” does not translate into “wreck a nice beach” on the screen! Then, and only then, Microsoft would begin to seriously think about integrating this technology into Windows. I don’t use Vista, but I hear that it does have some dictation software built in that is rather capable. The most robust software for PCs out there today is Dragon Naturally Speaking. For Mac users, you need to use MacSpeech Dictate (which licences the technology behind its software from Dragon). IBM had been developing ViaVoice for both platforms, but sold it to ScanSoft (now Nuance) in 2003. Nuance also owns Dragon, OmniPage, and PagePort. Thus, we really only have one speech recognition technology open to the end user at this point. Although each of these performs rather well, they are all designed to capture dictation and not natural speech. Punctuations need to be spoken – “period,” “comma,” “new paragraph,” etc. Even with a claim of 98% accuracy, an 8,000 word entry (this is what a professional transcriptionist can usually type per hour) will still contain some 180 errors that need to be corrected manually, not to mention all of the punctuation marks that I just mentioned.