Today I’m going to review two museums that offer an online version of their bricks-and-mortar museum exhibit. One is a national history museum, located in Berlin, while the other is a traveling temporary exhibit that has toured across Germany since 2003. In many respects they are not comparable, since the scale of the two sites and the resources available to each are quite different.

LEMO: Living Virtual Museum Online (LEMO: Lebendiges virtuelles Museum Online)

In the Federal Republic of Germany there are really only three federally funded museums at the national level – the German History Museum (DHM) in Berlin, the House of History (HdG) in Bonn (and since 2000 in Leipzig as well), and the Art Museum in Bonn. There is also the Martin-Gropius-Bau in Berlin, which is federally funded and has no permanent exhibit (other than the building itself), but rather hosts events and temporary exhibits that can be historical in nature, but can encompass any aspect of German cultural life. This virtual museum was actually a joint project between the DHM and HdG, with the DHM curating the pieces from 1871 to 1945 and the HdG those from 1945 to the present.

The purpose of the virtual museum, beyond preparing individuals and groups for their visits, is to provide access to its resources to an international audience, who might not have the ability to travel to Berlin to visit the museum personally. To this end, the “virtual” museum allows visitors to walk through a wide range of topics – both chronologically and thematically. A few years ago, you were also able to attempt a virtual walk through of the museum in 3-D. This was an interactive (and high-bandwidth) production that allowed the virtual tourist to experience the physical placement of items in the museum, push buttons to display more information, and zoom in to see digital versions of paintings and photographs on display at the “real” museum.For those who would like to see what that was like, they did preserve this function as a “guided tour” – but the visitor is no longer in charge of how one “walks” through the museum and all interactivity has been taken away.

Nonetheless, what we do have is a highly functional virtual museum. The epochs chosen are quite standard to the study of German history. Once you click on an era, say the Weimar Republic, the visitor is presented with a well-written overview of the period and its importance to understanding how the Weimar Republic fit within the larger history of Germany. The visitor is then given the ability to “drill-down” thematically – they could explore the revolution of 1918/1919, domestic politics, foreign policy, and other related topics. Once the visitor clicks on the theme, she is again provided with an overview and select primary documents (usually images) on the left that provide additional information.

Throughout each article, there are hyperlinks to primary texts and specialized essays that further enhance the ability of the visitor to learn about the topic they have chosen. The primary documents range from texts (digitized and viewable as a picture as well), sound clips, and videos. Often times, there are further “drill-down” options within the themes. Overall, the site is very accessible. Despite the fact that it isn’t as “flashy” as say the Digital Vaults project of the US National Archives, but it provides a massive amount of information on German history – much more than one could ever expect to gather in a traditional history museum – even among the largest national museums.

One very nice aspect of the site is a section called “Collective Memory” or Kollectives Gedächnis. Here, the website has solicited visitors (both real and virtual) to submit their memories about the time periods and events covered by the museum(s). Again, not as interactive as the Huricane Digital Memory Bank or even the new project by Der Spiegel called One Day or Eines Tages. But, since these memories are solicited by email and regular mail and then verified by museum curators, the authenticity of these oral histories take on a greater meaning for professional historians .

Against Dictatorship (Gegen Diktatur)

Another virtual museum site that is of note here is one that has been traveling around Germany since 2003 on the topic of the two dictatorships on German soil – the Nazi period and East Germany. This temporary exhibit was funded through federal monies and had a crew of professional museum curators who assembled the exhibit – including several academics who also work at major museums throughout Germany who served in an advisory capacity.

The emphasis in this exhibit is to highlight those Germans who resisted against dictatorship, many of whom fell victim to the regimes they opposed. Within the virtual museum portion of the website, the curators have provided thirty themes or sections, fifteen for each period. The site is not set up to allow direct comparisons between the two dictatorships – the themes chosen in each half of the exhibit do not parallel one another, but there are a few themes that do cross-over into both periods, such as youth opposition.

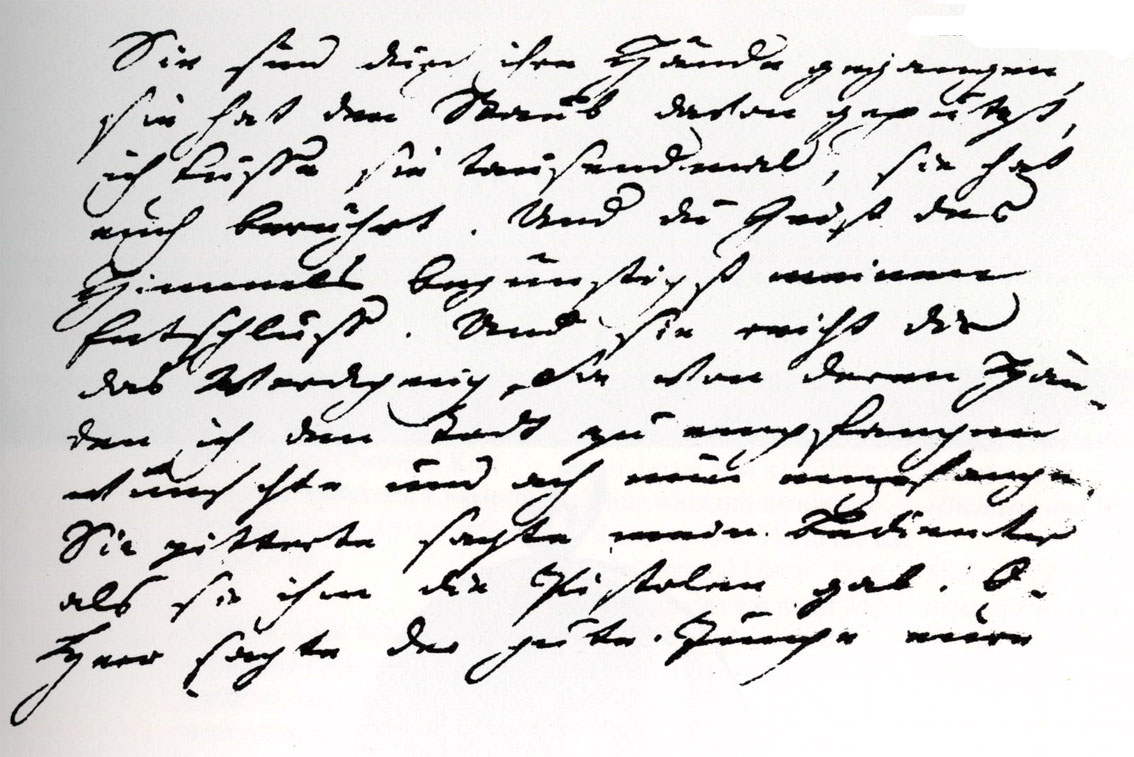

The texts that accompany each theme are short – assuming they are the same text that a visitor would have found had they seen the “real” exhibit in person – are well-chosen as representative of the topic that is being discussed and thus are paired very well. For those who want to learn more there are also “drill-down” elements that provide biographies of those involved and there are also primary texts and pictures provided for further reading and browsing. One potential problem is that some of the scanned images are too small to actually read some of the text, especially when handwriting is included. The ability to see the text as well as the original would have been a nice feature here.

An overall critique that needs to be voiced is that the virtual visitor is left without a guided tour of any kind. Visitors are free to pick and choose from what is offered. While there might be an advantage to this approach, the lack of any pedagogical guidance seems like a lost opportunity. Here we have a great example of a wonderful resource that could reach out to a much larger audience than the real exhibit, but the idea of guiding one through the evidence has been entirely removed from the “museum” experience.