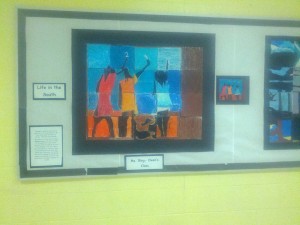

Each composite work has a small copy of Jacob Lawrence’s work for comparison. The exhibition also includes background curricular information, and information about Jacob Lawrence and his works. And yes, this image is kind of blurry. My phone camera is not the best. Actually it’s probably just that I’m a terrible photographer.

My kid’s elementary school has an amazing arts program, and they routinely display kids’ artwork all over the school. I was admiring a new African-American history themed exhibition, and appreciating how fair use makes this possible — likely, without any consideration of copyright or fair use by the instructors or administrators, and certainly without any by the children (with the possible exception of my child).

The recent exhibit featured re-creations of “the art of Jacob Lawrence, who tells stories about the history of African-Americans in his paintings.” This is part of the integrated arts curriculum in Amherst public schools, where the arts instruction is integrated into reading, social studies, science, etc. So the arts component of this involved the kids “look[ing] at pictures from [Lawrence’s] ‘Great Migration series’, which tells the story of the movement of many African-Americans from the south to the north at the beginning of the 20th century.”

After studying paintings, “[e]ach class worked on creating a replica of one painting from the series. Each student got a little piece of a painting and had the challenge of enlarging the shapes and recreating the colors. Then we put each of the pieces together like a puzzle.”

There were quite a few of these scattered through the building; I posted a couple of pictures below.

These paintings are among the best-known works of Jacob Lawrence, 1917-2000, drawn from the Migration Series, completed in 1940. The works are managed by the Jacob and Gwen Knight Foundation, which handles permission requests, and through the Artists Rights Society.

You don’t have to ask permission, because fair use.

But our arts teacher didn’t need to know about all this, and didn’t need to contact them, because the work is so obviously fair use. These children’s recreations are done in a nonprofit educational setting, and although they are recreating the works, they are doing so in a highly transformative way — closely examining individual components and recreating the components, then re-assembling to create a new work that looks something like a photomosaic. The original works were highly creative, but the level of transformativeness here means that second factor is less significant. The amount taken by each student was small, although the project as conceived of by the teacher is to take the whole of each work. But the whole of the layout and color scheme — and nothing of the actual brush strokes, the actual colors. And lastly, one can’t imagine that this use substitutes for any real or likely marketed use of the original — licensing to elementary schools to study art.

You don’t have to know fair use to use it.

Projects like this one happen in art classes, music classes, writing classes, all the time, from preschool rooms to postgraduate and professional work. (Preschool and elementary programs around here are fond of the colorful work of local celebrity children’s artist Eric Carle. In fact, the Eric Carle Museum of Picture Book Art has itself run arts activities of this sort, using Carle’s work as a touchstone.)

These kinds of projects happen all the time because copying is an integral part of how we learn, maybe THE most important part of how we learn. And they happen smoothly and beautifully, without asking for permission from copyright holders, and without some micropayment scheme monitoring and monetizing our every use of works. They happen so beautifully, easily, and intuitively, without transaction costs or surveillance or angst or paperwork — because of fair use.

And not because everyone had to know about fair use, and think about quantities and the four factors and so on. But because fair use is, at its core, a doctrine based on gut instincts, on what’s fair. So it can operate in the background, because that basic sense of fairness and unfairness is everyone’s guide: Is my use being unfair to the creator? The answer is so obvious most of the time that people don’t have to think further. Because the doctrine embodying a core limitation on copyright is based simply on what’s “fair”.

I like that. People shouldn’t have to become copyright and fair use experts to just run their lives. Even though copyright is ubiquitous (all of your cell phone photos, all of your emails, all of your doodles — all are copyrighted until 70 years after your death!), people are mostly able to operate without becoming experts, because of fair use*.

Who does need to know about fair use? Congress.

There are times and places, however, when I want the background benefits of fair use to be employed knowingly. The public interest copyright crowd was buzzing amusedly the last few days over a House Judiciary Committee’s animated GIF press release, ranting about immigration (trigger warning: Republicans ranting about immigration policy may send sensitive or sensible souls into apoplexy). Press pick-ups on this story included things like this article for ZDNet by David Gewirtz, which headlined the “copyright-violating animated GIFs.” (The ZDNet story, like this one, is actually celebrating fair use, while calling attention to the irony of its use by SOPA-proponents and the House Judiciary Committee.)

I’m happy they get to rely on fair use without knowing it, because we all can and should. But I hope someone, somewhere, was able to use this as a teaching moment to help them really GET why fair use is so important. Think of the children.

——————

* Fair use, and the de minimis doctrine, and other core copyright and general law doctrines that embody common sense.

Thanks to posts by Sharon Farb @ UCLA and Sherwin Siy @ Public Knowledge for alerting me to the House Judiciary immigration post originally.