Lauren Johnston: Animal Science

Emily Casey: Natural Resources Conservation

Zach Cross: Natural Resources conservation

Trees are often seen as the strongest of plants, sort of permanent structures that dominate and decorate our landscapes. But what if I told you that a small insect was changing that? Would you be skeptical, afraid or both? The hemlock woolly adelgid is an invasive insect running rampant through the Northeast, targeting the dominant canopy tree species of eastern and Canadian hemlocks. Landowners with this infestation on their property experience not only the great loss of these native New England canopy trees, but property damages and value declines when no management efforts are taken. But there is hope! With little time and money investments by private landowners, this infestation can be controlled before its too late to see our hemlocks in abundance again. Figure 1 exemplifies just a portion of the vast loss of hemlocks in a Pennsylvania forest.

Figure 1 Skeletal remains of hemlocks plagued by HWA infestation shown in the PA forest (http://www.americanforests.org/magazine/article/the-last-of-the-giants/).

Introduction

Species have been able to cross global boundaries that otherwise may have never been reached since humans have been able to access far-away areas regularly for the last 50+ years. Even though introduction to new areas is generally accidental, as with the hemlock woolly adelgid, these species may still pose a great threat to the native communities. In Crooks’ (2002) study, he explains that species that have a “net negative” effect on native communities are considered invasive as they generally decrease habitat complexities, species richness and abundances, and contribute to homogenizing the environment (p.153). He further argues that invasive species are able to impact their introduced habitat this way by altering the physical resources of the habitat in favor of their rapid and widespread success (Crooks, 2002). In order to grasp the seriousness of the extent of an invasive species on a native forest community, Kok and Salom’s (2014) study explain that the hemlock woolly adelgid has caused widespread hemlock mortalities where the infestation has affected 50% of the geographic range of eastern hemlocks since its accidental introduction from Japan. Sadly, we can easily see the effects of these species by looking out our backyards into the depleting hemlock-dominated canopy forests that were once a trademark and abundant Northeastern tree.

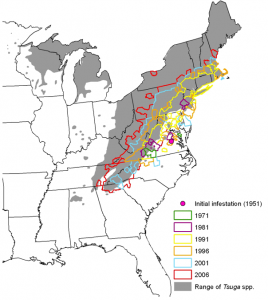

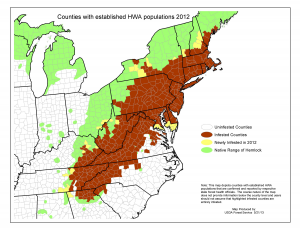

By now you are probably wondering what exactly is this adelgid and how does it manage to have such a huge impact on our New England forest ecosystems. The hemlock woolly adelgid reproduces asexually with 2 generations per year and can lay 100-300 egg sacs between hemlock branches. The larvae of this insect are easily spread by wind, mammals, and birds and can feed on the sap of all ages of hemlocks. While feeding, the adelgid may also inject a toxin into the trees (Pennsylvania Dept. of Conservation, 2014). The effects of this invasive pest on hemlocks include: needle loss, inability to produce new growth, and ultimately death within 4-10 years. Even if the hemlocks do not die directly from this infestation, they are severely less resilient and often die from other environmental stresses (Havill and Salom 2014). Figure 2 depicts HWA underneath eastern hemlock needles. Currently the hemlock woolly adelgid has reached 18 states, from Maine to Georgia, with vast infestations occurring in 7 (Maine DACF). Map 1 shows how the infestation has developed from 1951-2006. Map 2 illustrates a clearer representation of the current status of the invasion’s spread. Based on the 2011 data of Map 2, the most dense areas of infestation are occurring in MA, RI, CT, DE, MD, WV, and PA where all or close to all of the hemlock’s native range is impeded by the HWA’s invasion. For instance, in their article, Small, Small and Dreyer (2005) state that over the course of their 20-year study in southern Connecticut sites, they examined a 70% decrease basal area of hemlocks between 1982-2002 (Small, Small & Dreyer, 2005, p 458).

Map 1: U.S. Forest Service Forest Health and Protection’s historical spread of HWA outlined in various colors and overlayed on native range of hemlocks shown as gray shading. (http://www.nrs.fs.fed.us/disturbance/invasive_species/hwa/risk_detection_spread/

Map 2: USDA Forest Service’s most current map of the spread of HWA as of 2012. Infested areas are shown in the rust color and are overlayed onto the native range of hemlocks shown in green (http://wvpublic.org/post/scientists-try-save-endangered-hemlock-trees-west-virginia-swamp).

Thesis and Target Audience

We believe social involvement by private landowners is imperative in the control and management of hemlock woolly adelgid in response to the alarming economic and ecological impacts of this infestation over the last 20 years. This involvement consists of actively identifying and eradicating the insect on the hemlocks on your property in order to save your trees and control the invasion’s spread via products that inexpensive, easy-to-use, and take little time to apply. While this task may seem intimidating at face value, inaction will result in a much bleaker not-so-distant future for our forested ecosystems and personal property values.

Private landowner involvement to control this invasion will exemplify how important these stakeholders are to provide sustainable stewardship of forested landscapes in Massachusetts and larger New England. We believe the private landowners of Massachusetts should take primary responsibility to control and manage HWA in the state because the majority of forested land in MA is privately owned. For example, of the 62%+ forested land in MA, about 75% is privately owned (Catanzaro 2014). This means that hemlock-dominated forests are statistically more likely to be in your backyards and you are a direct stakeholder in this invasive issue. Current property owners, future successors of their property, and the many recreators and resource users will receive the most beneficial experiences from their lands from their involvement. Outside of the human values of trees and forests in terms of aesthetics, recreation, and culture etc., their values are vastly important for the maintenance of our environment.

As a dominant canopy tree, hemlocks traditionally envelopes canopy layer services including: primary productivity support via rapid photosynthesis, protection of lower forest layers from environmental factors like harsh winds/storms, providing habitat to unique wildlife and plants, and creating a microclimate suitable for various inhabitants in lower forest layers (Lowman and Moffett 1993). Beyond their role in the forest structure, hemlocks contribute additional ecosystem services. For instance, Small, Small, and Dreyer (2005) explain how hemlock trees are a vital component of the New England forest system. They provide ecosystem services such as: erosion control along riparian areas, enables ground stability, acts as a carbon sink, aids in water purification and retention, provides food for deer and other wildlife, creates shelter for wildlife during the harsh New England winters, and is a source of lumber for our many wood products. Hemlock trees are described as the “most shade tolerant and long-lived tree species in eastern North America” (Cheah et al. 2004). With help from a direct stakeholder, private landowners, we can restore one of the most quintessential New England trees back into abundance and strength throughout our forests.

Economic Impacts

The impact of invasive species extends far beyond that which native communities experience and include some very real economic concerns for property owners and tax payers alike. Pauling and Rieske (2010) argue that these species threaten global economic and ecological interest and they are considered a major cause of extinction via habitat alteration, predation, and competition. For example, Marten and Moore (2011) claim that of the 50,000+ non-native invasive species, there has resulted $115 billion in annual damages and losses with a control investment of $21 billion in the US alone. And in terms of its impact for residential landscapes, a New Jersey case study uses empirical models to show the economic damages that are experienced when hemlocks reach moderate (25-50%) defoliation via the infestation (Homes, Murphy, and Royle, 2005, “Discussion). Their results illustrate that a 10% increase in the average area of moderately defoliated hemlocks reduces property values by $7261 per house at risk. For a neighboring house at risk, property values can reduce by $2331 also with this amount of increased defoliation (Homes, Murphy, and Royle, 2005, “Results”). The products (available at local garden centers, amazon.com etc) used to combat this infestation could save these high costs that landowners would otherwise experience if no management efforts were to be put into effect. For instance, the common sprays are about $5 and insecticides are about $30. While their application methods are explained in detail later, these products can last landowners years. Landowners with houses at risk could spend the same amount of money as the projected property value decreases toward 1452 spray bottles or 242 insecticidal treatments that could potentially manage the infestation on a regional level. The threat of this invasive insect poses a steep monetary concern for property owners and neighboring houses alike and therefore requires these stakeholder’s attention and action.

Ecological Impacts

Because the economic aspects are not enough to fully grasp the reality of HWA’s infestation, the following ecological impacts are addressed below to further induce the need for your participation in this invasive fight as a private landowner. However, as a disclaimer, many of the ecological impacts of this invasive species (or any other) are not quantified yet since research on them may take decades before they are holistically understood, especially since invasive ecology is a relatively new field of study for scientists. The loss of a dominant canopy tree species poses many implications for dramatic changes to occur at the ecological level. As of yet, researchers have made conclusions about changes in landscape structure, composition, nutrient cycling, and wildlife habitation in areas experiencing hemlock mortalities in response to HWA invasions.

The decline of hemlock abundance and strength as canopy trees has created a shift in dominance. These shifts in dominance are important because they influence the forest’s species composition as environmental factors like light availability, precipitation infiltration, and nutrient cycling also shift. As the hemlocks decline and make way for more light availability and exposure to the overall environment, the forest compositions will likely change from the quintessential shade-tolerant species to ones that can accommodate more light/precipitation intake; this will change the characteristics of our New England forests forever without you aid to control the HWA infestation. For instance, in their article, Small, Small, and Dreyer (2005) examined that the canopy dominance changed from hemlocks to oaks and mixed hardwoods in their Connecticut study sites. As hemlock basal areas dramatically declined, oak basal area increased from 28-41% from 1982-2002 (Small, Small & Dreyer, 2005, p 458). They also attest that the hemlock declines have resulted in overall increased understory growth characterized by increased shrub richness, sapling density, and herb species frequency. Additionally, Stadler, Muller et al. (2005) reported that black birch density and abundance were regionally increasing in response to hemlock decline in southern New England forested areas.

Researchers have also concluded that hemlock mortality has affected nitrogen and throughfall (excess rain drops shed from leaves that have erosive power) processes. In both of their articles, Stadler, Muller, et al. (2005) and Jenkins, Aber, and Canham (1999), the authors’ studies claim nitrogen availability and rates increase following HWA infestation. While nitrogen is a necessary nutrient needed for plant growth, overabundance of it is problematic. For instance, in their articles, Jenkins, Aber, and Canham (1999) suggest the levels of nitrate (component of nitrogen cycle) could result in nitrate leaching. This poses concerns for public and ecological health as leaching of this nutrient can contaminate groundwater that we depend on for fresh drinking water and damage aquatic ecosystems downstream.

Also, in their article, Stadler, Muller, et al. (2005) attest that “throughfall chemistry, quantity, and spatial patterns” were highly affiliated with HWA infestation. The authors examined that throughfall to the ground reached 80-90% of the total precipitation quantity (Stadler, Muller, et al., 2005, “Abstract”). This poses a threat of soil compaction in sites with HWA invasions as an inability for nutrients and water to percolate into the soil occurs and ultimately results into erosion and overall ground instability. Cumatively, this could also contribute to downstream water quality issues depending on the severity and proximity the forested area is to urban areas where this is already a problem. While these nutrient responses might not directly impact your health as a private landowner, if you could reduce the chance of water contamination for your fellow community members by purchasing an inexpensive insect control product, wouldn’t you?

Finally, researchers have studied how avian species respond to the loss of their hemlock habitat. In their article, Tingley, Orwig, et al. (2002) determined that HWA-induced tree mortality has “profound effects on avian communities” (Tingley, Orwig, et al., 2002, “Conclusion”). The authors (2002) examined that black-throated green warblers, blackburnian warblers, and Acadian flycatchers are among the bird species that experienced the greatest sensitivity to hemlock canopy loss in their Connecticut study. One of the most popular recreational activities of forested areas that New Englanders engage in is bird-watching. Seasonal changes and the large variety of bird species that inhabit our landscapes provide birders with exceptional places to visit and watch birds. As many birders are probably private landowners since their land would provide them with the recreational activity they love, the habitat loss of hemlocks associated with specific bird species might be of particular interest for them to decide to invest in controlling the HWA invasions.

Proposal

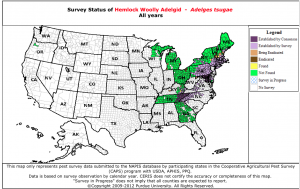

We call upon the immediate action of private MA landowners to contribute to the restoration of hemlocks as dominant canopy trees that represent traditional and historic Northeastern forests. Why immediate? Map 3 represents the current spread of HWA and status of eradicated populations of the insect in the US. The eradicated populations shown here are miniscule compared to the entire spread of the infestation, where none of these eradications have been met in MA. By actively identifying, controlling with products, and sharing the location and status of the HWA invasion with your community and larger Internet network, your efforts will establish the control and hopefully eradication of HWA that we are seeking.

Map 3: Survey of HWA status of established, eradicated, and not found populations (http://livingwithinsects.files.wordpress.com/2012/05/map-print-preview.png)

First and foremost, accurate identification of the hemlock woolly adelgid on your part is easy and takes little time. Landowners when determining if their trees are infested or not can look for specific signs. Townsend & Rieske-Kinney (2010) help landowners identify infection by explaining that landowners can start by looking for small white sacs, which resemble a cotton ball like structure, along the needles of branches that are infected. Trees that do not show signs of infestation generally do not need treatment but if they were within close proximity of other infested hemlocks it is recommended to treat them to prevent future infestations that may occur due to spreading. Private landowners are encouraged to research the stages of the HWA infestations so they can properly treat their Hemlocks. Proper treatment could also help save landowners money in the long run. Treatment can help to prevent the trees from becoming weak due to infestation and reduce the risk of property damage or tree removal services due to a fallen tree. Since chemical control is not difficult to apply, a local garden or pesticide shop would be able to provide details and assistance along with proper application as directed by the bottle. Control options are based on the size and stage of the infestations. For chemical controls landowners can have an option of two different controls methods. The first option is to buy an insecticidal soap or horticultural oil and spray the foliage of your infected trees. The second option is to use a systemic insecticide that moves with the tree sap upwards through the tree and helps to kill the adelgids out of your reach(Townsend & Rieske-Kinney, 2010). The private landowners themselves can apply the option of insecticide spraying if trees are small enough. If trees are too big, spraying as much as the tree as possible will allow for some restoration of the Hemlock. Commercial insecticide applicators can be used to treat large scale Hemlocks that are infested that landowners cannot simply reach on their own. Of the insecticide spray, Talstar has been known to work the best and is very useful for landowners who have not experienced this infestation before. It has lasting effects of upwards of two to three years of preventing infestation on trees (Sidebottom & Bedenkamp, 2009). This control would work best for all landowners who are not familiar with the HWA life cycle and still allow for effective control. The second option of a systemic approach can be applied in three different methods. Soil drenching/injection and trunk injection methods are most practical systemic treatments for full tree coverage. It is important to read how much area the insecticide will treat so that you can cover the full base soil area. Townsend & Rieske-Kinney (2010) explain that “The appropriate amount of insecticide, based on the product label, [should be] diluted with water and applied evenly to the soil surface or into a series of small holes spaced evenly around the base of the tree at a distance of 6 to 12 inches” (para. 8). This will allow for the most effective control of the insecticide. Trunk and soil injections while an effective control method would be most efficiently provided by a commercial pesticide applicator. Any licensed applicator in your state can provide this service for the infested Hemlocks. To ensure the restoration of the Hemlocks from the HWA infestation, it is important to apply proper follow up treatment. It is important to refer to the specific insecticide chosen for treatment to see how long it will be effective until more treatment is necessary. The treatment and upkeep of the infestation is crucial to the survival and renewal of the Hemlock trees.

Resistant Audience

It’s easy to dismiss this problem like everything else. Just like global warming and overpopulation, it’s easy to push those issues aside since they will affect future generations and not you. But here’s a chance to step up, to step up in an easy way that has a multitude of benefits. Everyone can say they want to save trees and make the world a better place, but we need action, not words. We need immediate action taken against the hemlock woolly adelgid if we want to stem the infestation and prevent the westward spread across the United States.

“This sounds like a job for the government! If it’s spread all across northeast U.S. then it should be their responsibility!” We understand that it sounds like a job for the government. We understand that you shouldn’t have to take responsibility for a problem so large and widespread. But it’s no longer feasible to dump the problem on the government. As we’ve said before, the hemlock woolly adelgid is found all across the eastern part of the United States and is continuing to spread. A governmental agency does not have the manpower, nor time required to fight this battle. For it to be feasible, a large portion of our tax dollars would have to be directed to this project. Governmental actions are also notoriously and we cannot afford to wait any long to take action due to the rapid spreading of the HWA both south and westward.

“This sounds expensive and like it would take a long time!” This isn’t true! We mentioned earlier that there are multiple control methods at a range of costs. The cheaper spray methods, that cost about $5.50 on amazon.com, only have to be applied annually and application is as simple as spraying the needles of the tree. Compared to the time you spend mowing, gardening, or weeding, this amount of time is nothing. Spraying the hemlocks on your property could actually be a financial gain. The hemlock woolly adelgid deprives the trees of their nutrients which causes a tree to become weaker and weaker. This increases the risk for the tree to fall. It would be more beneficial financially to spray your hemlocks yearly, then to rebuild a section of your house, buy a new car, or pay for any other damages a falling tree can cause. The only caveat is if your hemlocks are at a height that you are unable to reach. In this case, you have two options. You can hire an arborist to come and spray your trees, which will ensure proper application and effectiveness. If you don’t want to involve anyone else, or you don’t want to pay for that service, you can inject/drench the base of the tree with a different chemical, imidacloprid, which is a bit pricier at about $30. Even though it might sound daunting, treating your trees is not expensive and does not take a long time.

Conclusion

The hemlock woolly adelgid is a pest that is causing a lot of damage. Hemlock has been a vital part of the New England landscape forever and it’s hard to picture the scenery without it. But in addition, the disappearance of this tree carries other harder to picture repercussions. With the loss of hemlocks, Small, Small, and Dreyer (2005) predict that ecosystems and their hydrologic processes will undergo major changes, the diversity of understory species will diminish, and the ability of other invasive species to infest our forests will go up (pp. 458-464). The preservation of the eastern hemlock is necessary to prevent these negative changes, and the only way to do that is to fight the hemlock woolly adelgid. It’s in the hands of the private landowners to fight this battle and we hope they take up arms. Fighting this battle doesn’t require much sacrifice, just a few bucks and a weekend every year. With victory comes the preservation of a unique and iconic New England species.

Wow, happy to see this awesome post. I hope this think help any newbie for their awesome work. By the way thanks for share this awesomeness from

Thanks for sharing

VEGUS168S

vegus168

Nova88 Slot

Nova88

info slot gacor hari ini

bocoran slot online

rtp slot pragmatic