Aristotle (384-322 BC) established the philosophical basis of physics with his “natural philosophy,” and is also considered one of the greatest philosophers in history.

As such, much of his work in physics is speculative but offers a great deal of insight. He did contribute real research to several areas of science, and had incredible foresight for an intellectual from the age of classical antiquity.

Significantly, Aristotle espoused a certain belief in inductive reasoning which was not found in his more deductive teacher, Plato. Therefore, Aristotle’s philosophical method at least more closely resembled the current scientific method that did his teacher’s. According to Aristotle, he studied phenomena which were caused by “particular,” which was then a reflection of the “universal,” or the set of physical laws. Aristotle also described “science” as “… either practical, poetical, or theoretical.”

One of the many fields to which Aristotle contributed was the field which he called “natural philosophy.” He regarded “natural philosophy” as a “theoretical” science. Aristotle devoted most of his life to the natural sciences, contributing original research to physics, astronomy, chemistry, zoology, etc. Aristotle expressed an early teleological belief in saying that natural things tend to certain goals or ends. Teleology is the philosophical belief that there are certain final causes in nature. According to Istvan Bodnar, in The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, “Nature, according to Aristotle, is an inner principle of change and being at rest (Physics 2.1, 192b20–23). This means that when an entity moves or is at rest according to its nature reference to its nature may serve as an explanation of the event.” Essentially, Aristotle believed that reference to the innate qualities of an object (whether it is at rest or in motion naturally) would assist in determining what caused an event. Of course, we now know that objects are set in motion when acted upon by a net force and tend to stay in motion until another net force acts upon it. However, Aristotle made an important point with this idea: that forces acting upon objects can either set them in motion or make them tend towards rest.

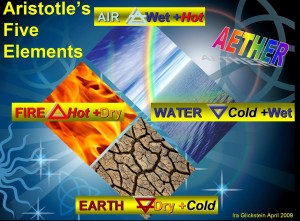

One of Aristotle’s more famous ideas of natural philosophy is his addition of the celestial “aether” to the four natural elements suggested by Empedocles. The “aether” is, according to Aristotle, the “greater and lesser lights of heaven.” By this, Aristotle meant the stars of the universe which were visible to him in the night sky. The other four natural elements (fire, earth, air, and water) are able to change and mix, according to Aristotle. This is an early precursor to modern ideas of phase transition. These elements are capable of “generation and destruction,” as opposed to the aether, which is unchanging. Aristotle concludes that these bodies cannot be composed of the four elements, because they are not capable of change. Fire, earth, air, and water are terrestrial elements while aether is a celestial element. The most important point is that Aristotle redefined natural elements to include early ideas of phase transition.

Aristotle also made an important attempt to explain gravity. His theory was that all bodies move toward their “natural place.” Natural places are also based largely on composition (of the natural elements). For example, since many commonplace liquids are composed at least partially of water, they move towards sea-level, where the oceans are, or down towards the ground, where ground water can be found. Or, since smoke is air-like, it moves up into the atmosphere where air is. This was the way in which Aristotle described general motion. Aristotle also believed that vacuums did not exist, but that if they did, terrestrial motion in a vacuum would be infinitely fast.

Aristotle described celestial motion in terms of crystal spheres, which carried the sun, moon, and stars in unchanging endless circular motion. In Metaphysics, Aristotle says “that there must be an immortal, unchanging being, ultimately responsible for all wholeness and orderliness in the sensible world. And he is able … to discover a good deal about that being…” This is his concept of the “unmoved mover,” which is capable of moving other things without being moved. An “unmoved mover” is reminiscent of the modern idea of gravity, which is not actually a physical object but does cause motion without any other motion being necessary.

Highly significant was Aristotle’s argument that the Earth was actually spherical. He believed that the Earth was a small sphere. Since he could see stars in Egypt and Cyprus which he could not see further north, he concluded that this was because the Earth is a sphere and is small because such a significant change in the sky would not happen unless on a small sphere. Based on his theory that the earth element tends towards a center, just as all water heads down to seal level towards the concentrically spherical ocean and all air tends to move upwards to form a concentrically spherical atmosphere, he theorized that the Earth was a sphere. Further evidence Aristotle used to support his round Earth theory was that the shadow the Earth imposes on the Moon during a lunar eclipse is round.

Clearly, Aristotle made some significant contributions to the field of physics. He made several further contributions to physics, cosmology, and astronomy. Aristotle defined the scope with which Western culture would observe nature and theorize about physics for centuries. There would have been no Newtonian physics without the strides made by Aristotle. There are several more contributions to physics which could be covered here, but due to limited space, they must be discounted for now. In the next post, the ideas of Archimedes will be discussed, perhaps along with those of some later Greeks.

For further reading, see the sources page.

Great website you have here. You have such a beautiful way of writing. Thank you for sharing this, it’s very helpful for some people like me.

Karya Bintang Abadi

good