There are a lot of vowels in English, and they don’t seem to be comfortable in the space they are in. They are constantly moving, pushing (or pulling) each other around. The Great Vowel Shift, which happened from about 1400 to 1700, is responsible for a lot of the mess in the English spelling system, with written letters having multiple pronunciations (how many ways can “ough” be pronounced? Ought, though…), and vice versa (how many ways can you write the vowel sound in “ways”?).

Less well known are the modern vowel shifts, but the more they are studied, the more likely it seems that are happening everywhere English is spoken. William Labov first documented the Northern Cities Shift, which can make “buses” produced by someone in Chicago or Detroit sound like “bosses” to most other North Americans, and “block” sound like “black”.

The Canadian shift (see the concluding paragraph below on its current name) has largely gone in the opposite direction of the Northern Cities Shift. Because of this, when I first moved to Western Massachusetts from Canada, a potential landlord thought I was telling him I had a cot (and seemed puzzled that I thought he needed that information) when I was in fact telling him I had a cat.

A 2022 study by Matt Gardner and Rebecca Roeder provides a particularly clear picture of the Canadian shift in their Figure 8. Each of the arrows corresponds to a vowel whose pronunciation differs according to the age of the speakers (which is called a change in “apparent time”). The speakers are all from Victoria British Columbia, and range in age from 14 to 98.

The vowel from “cat” is represented by TRAP in Fig. 8. This diagram is plotting vowels according to acoustic measurements that correlate with the height and frontness of the tongue. Vowels closer to the top of the vowel plot are produced with the tongue higher in the mouth, and vowels further to the left are articulated with the tongue further to the front of the mouth. So the new pronunciation of TRAP has a lower, less front vowel.

In the Northern Cities Shift, the TRAP vowel has moved frontwards and up, towards the DRESS vowel. You can hear this in a speaker from New York City saying “bad”, or a speaker from Chicago saying any short-a word. In the Canadian shift, the vowel has gone in the other direction, towards what you might be familiar with in many Boston speakers’ pronunciation of “father”. The relatively back position of the Canadian TRAP vowel may be part of why it is used in the Canadian pronunciation of “pasta”, since it is not far from the Italian vowel in that word.

Surprisingly, another recent study, published by Monica Nesbit and James Stanford in 2021 finds that the TRAP vowel has shifted in the Canadian direction in Western Massachusetts rather than in the Northern Cities direction. This is shown in a pair of vowel plots in their Figures 5 and 6, showing the positions of the vowels for the oldest and their youngest speakers. This diagram uses BAT for the TRAP vowel. For the older speakers, it is remarkably high and front relative to DRESS, but for the younger speakers it is quite a bit lower and a bit less front.

This raises a puzzle for me: why did my young interlocutor mistake my Canadian “cat” for “cot” if we had the same TRAP vowel? My guess is that Western Mass is home to wide range of vowel systems, including those of natives of other areas with Northern Cities-style raised TRAP and fronted LOT vowels. There is probably also some regional variation within Western Mass along the I-91 corridor. Meghan Armstrong-Abrami, a linguist native to East Hartford, says she thinks people from Holyoke and Springfield often sound similar to Hartford speakers. It would also be useful to know exactly where the Canadian and Western Mass vowels are relative to each other: we can’t tell by comparing these vowel plots since they use different scales.

If you want to hear a Western Mass speaker, you can listen to a podcast of Bill Dwight, who has been called the spirit of Northampton (he was born in Holyoke). The students in my UMass “Sounds of Englishes” class and I will be listening to him and analyzing his speech, and it will interesting to see where it lands in the crowded English vowel space.

As you may have noticed in the figure caption for the Canadian shift, it has now been given the name of low-back-merger shift. The renaming has happened for two reasons. First, it’s clearly not just a Canadian thing: as well as the new Western Mass example, it’s long been known to have happened in California. Second, the new name gives information about an important characteristic of these shifts that we haven’t gotten to yet: that the lowering of the TRAP/BAT vowel is accompanied by the merging of the THOUGHT and LOT vowels (low back vowels). For Canadians, and increasing numbers of speakers in the United States, “cot” (a LOT word) and “caught” (a THOUGHT word) are pronounced the same. And in the vowel plots above from both Canada and Western Mass, you can see that the older speakers produced the THOUGHT and LOT vowels differently, and the younger ones produced them the same. The Western Mass case is particularly interesting because it seems to reverse the chronology of the change from what happened in Canada: according to Nesbit and Stanford, the lowering of the TRAP vowel happened before the the merging of the THOUGHT and LOT vowels.

Update 11/24: Just got myself a copy of Edward McClelland’s How to Speak Midwestern, which is a wonderfully accessible, informative, and fun introduction to the Northern Cities Shift and much more. I read it in one sitting, and feel like he got the linguistics right – I also learned a lot.

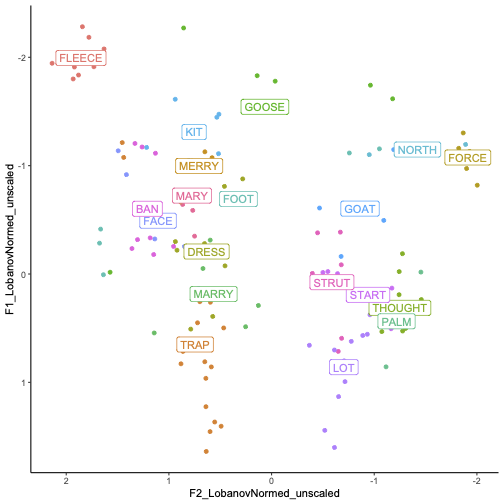

Update 12/3: Here is a plot of Bill Dwight’s vowels from a word list reading. As in the above plots, the labels indicate mean values for the vowel classes. He falls in between the two generations whose vowel plots are shown above, in having TRAP lowering but no THOUGHT/LOT merger. TRAP lowering first is the order Nesbit and Stanford infer from their statistical analysis of a larger set of speakers. He was born in 1955, in between the birth years of the older and younger speakers.

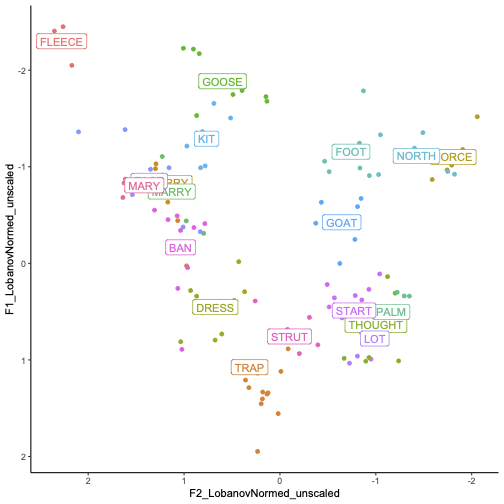

And here is a plot of mine: a more centralized and slightly lower TRAP than Dwight, a lower and more central BAN, and no LOT/THOUGHT contrast (or MARY/MERRY/MARRY).

The fact that my TRAP is between Dwight’s LOT and TRAP may well be related to the cot/cat confusion I experienced. It is also interesting that Dwight’s TRAP is not as low and central as the younger speakers in the Nesbitt and Stanford study. It seems likely that TRAP would only be that low and central if LOT is in the further back and higher part of the space, as it is for me and the younger Western Mass speakers.