From Joe Pater.

My impression is that women are relatively well-represented in phonology, maybe more so than in other sub-disciplines of linguistics. A little piece of encouraging data on this comes from the 2015 Annual Meeting on Phonology, in which 18/27, or 66%, of the authors of oral presentations , including plenaries but not tutorials, were women (I was unable to identify the gender of one author). I’d be very interested if anyone has any better data on the representation of women in phonology, especially with respect to semantics, syntax and phonetics.

I also have the impression that women are under-represented in phonological discussion, that is, in question periods and other discussions at conferences, and I suspect this is part of a much broader phenomenon. A piece of data on this also comes from AMP 2015. Kie Zuraw kept track of the gender of question askers for 16 of the talks (all but the first two). 74/103 = 77% of the questions were asked by men, even though the audience was about equally balanced between men and women. Zuraw’s observations replicate previous observations by Stephanie Shih from the Computational Phonology and Morphology Workshop held July 11 2015 at the LSA Summer Institute, in which the audience was roughly gender balanced, but the question takers skewed male. Inspired by Shih and Zuraw’s observations, I kept track of the gender of question takers at the LSA Phonology: Learning and Learnability session January 7th, 2016, and got 26/29 = 90% male questioners, with what looked again to be a roughly gender balanced audience.

These results are not surprising – I think they are just confirming what we’ve all informally observed in conferences and elsewhere (though I have to say that I was surprised at how skewed my own count was). There is undoubtedly a complex set of conscious and unconscious biases underlying our behavior that’s producing this distribution, and presumably there is a literature in some field that has studied related phenomena. My current thinking is that there are some pretty obvious conscious decisions we can each make to change this distribution, and that simply talking about this phenomenon and raising awareness of it may well help to get a better representation of women in phonological and other academic discussion. I do hope this situation changes, because I’d very much to like to hear more of my female colleagues’ thoughts after talks.

Thanks to Ellen Broselow, Jenny Culbertson, Claire Moore-Cantwell, Magda Oiry, Stephanie Shih and Kie Zuraw for discussion.

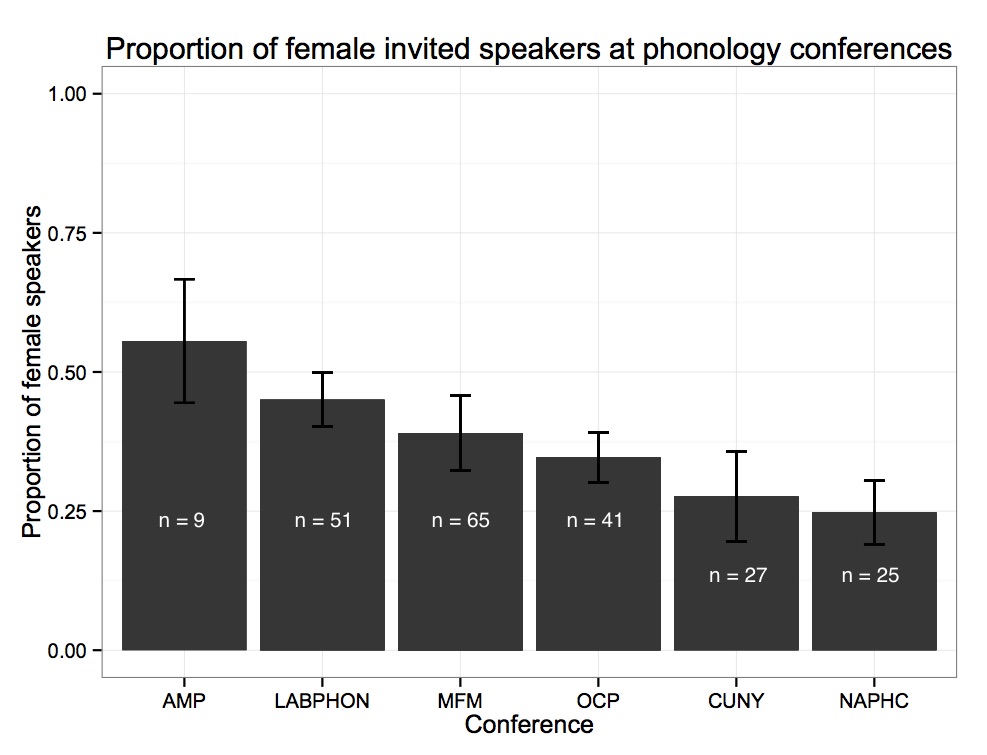

Update Jan. 10th: Thanks to someone who prefers to remain anonymous for the following graph, which shows we still have some work to do in terms of representation of women as invited speakers. The ns in the graph are the total number of speakers.

Update Jan. 12th Sharon Peperkamp has shared “data for 53 conferences between 1993 and 2013, for a total of almost 300 invited and more than 2000 selected speakers, with 37% invited vs. 49% selected women”. It’s great to see that women are indeed well represented in phonology in general, and this makes it even clearer that we have work to do on the invited speaker numbers. Sharon has also contributed this plot of percentages over time.

The spreadsheet is available here, if anyone would like to further analyze it, make figures, or continue to keep track of the numbers. If someone wants to volunteer to coordinate this effort, please e-mail me, and I’ll put that information here. As Rachel Walker has pointed out to me, conferences could also keep track of diversity statistics themselves – apparently she’ll be bringing this up with the AMP board. If this happens, we could keep a consolidated public record here.

Once the discussion has started, we (as senior members of our field) could all make a special effort to follow up on something a woman has said before: elaborating a point, adding a comment, explicitly acknowledging that we are following up on another person’s contribution. I have often observed (or experienced) that if you follow the dynamics of a discussion, contributions by men are more often acknowledged in follow-ups than those made by women. Sometimes, this happens even if a man and a woman have made similar points (or even the same points) in the same discussion. If you see a connection with the work of a woman who is also present in the discussion, you could mention it and explicitly draw her into the discussion in that way, maybe by asking her a question related to the connection you see.

Thank you, Joe, for bringing up this important issue (and also of course to those you credit in your post for inspiration and discussion). By a remarkable coincidence, there is a phonologist who I know would have a lot to contribute to this discussion: Curt Rice (http://curt-rice.com/about/). Among his many hats, he leads Norway’s Committee on Gender Balance and Diversity in Research (http://kifinfo.no/) and posts regularly on his blog about gender equality (http://curt-rice.com/category/gender-equality/) in areas including (but not limited to) academia. In case he’s not already reading this, I’ll pass this post on to him.

Another coincidence: Curt and I attended an open access conference together back in December where he observed that, while the (invited) delegation overall did not skew too sharply male (maybe it was 60-40 male? I’m not sure), all but 2 panelists were male — and one of the female panelists was reporting primarily on her male collaborator’s work! Curt live-tweeted his observations (@curtrice, #berlin12).

I was talking about this post with my wife (who is also a linguist) over breakfast, and she told me that it reminded her of a story by Sheryl Sandberg. It goes something like this. At a certain conference, there was time for only three questions, and hence the chair asked the audience to limit their questions to three. After three questions had been asked, it was only men who raised their hand for an additional question. Are men more willing to “break the rule”?

http://www.ted.com/talks/sheryl_sandberg_why_we_have_too_few_women_leaders#t-524634

See 9:00 and on. My wife’s recollection was not entirely accurate, but the point still holds and is relevant.

Interesting graph. Good for the AMP!

It’s a small sample, but it’s a good start.

Yes! Good job AMP!

Can I ask if those invited-speaker numbers happened organically, or if it was quota-driven? I ask because I also have the impression that the gender balance at phonology conferences is pretty good, but it also seems (impressionistically) that the female participants skew to the more junior side. Does anyone have numbers on that? If I’m right, this surely has an impact on the question period data, and the invited speaker data.

This is also a question for Adam Albright and his colleagues at MIT, and Gunnar Hansson and his colleagues at UBC/Simon Fraser (each year’s local organizers are responsible for the program) – I’ll forward the link to them. Speaking for the UMass organizers, our quota system was that we wanted one senior, one junior, and one mid-career speaker. I don’t remember the question of gender coming up. It would have if none of our speakers had been women, and we would have made sure to include at least one. The relatively good representation of women comes from the following years: we only had one female invited speaker.

By the way, I’m not interested in patting ourselves as AMP organizers on the back, and I’m especially not interested in pointing fingers. The point that I’d like us to take away from this is that women are sufficiently well represented in our field to be equally represented as invited speakers. If it turns out that the skews are at least partly due to age, then working to have more junior invited speakers, and more questions from junior participants seems like a worthy goal too. Impressionistically, I don’t think the male questions skew old though. I also see women as well represented amongst senior phonologists, but that’s probably a local view.

What Joe described is also how we approached the selection of invited speakers for AMP 2015: one each from the (roughly) junior vs. mid-career vs. senior categories. In our case, it turned out that it was the most junior of the invited speakers who was male, with the other two both female. While that was not part of any deliberate strategy on our part, I think it’s fair to say that we were certainly happy about that outcome.

Thanks, all, for putting these numbers together. To address Heather’s question, for AMP 2014, we aimed more for diversity of approach than levels of seniority, aiming for a mix of “traditional phonological analysis” (e.g., language-internal and typological evidence), experimental evidence, and computational modeling. This ended up leading quite naturally to our invited speaker list, with two women and one man.

I think other types of balance, such as geographic, theoretical, and gender, were also on our minds, so I suppose it probably entered in some implicit way into our brain-storming. As Joe says, the question would have arisen explicitly if we had come up with an all-male list. However, we were pleased to see that this was not necessary!

Funny – we also aimed for diversity of approach in exactly the same way, though I don’t remember ever talking with you about this Adam!

We raised the issue of aiming to improve gender balance for invited speakers at MfM at the last business meeting. We are aware that we have not achieved balance in the past, and so it’s something we’re working on. It’s great you’ve raised this issue for other conferences. At the last MfM a woman colleague and I also noticed that the discussion was dominated by men. It’s good to have some tips about how to change the balance here, too.

Thanks for this Laura – I also think Angelika’s tips are valuable. It’s important for men to recognize the gender imbalance in discussions, and to do their part. I know I’ll be more aware of this now when I’m selecting questions, and also when I’m deciding whether or not to ask a question.

Here’s some interesting stats from the ‘Phonology, Morphology, and the Lexicon’ session on Sunday at the LSA: in that session, question asking was almost exactly balanced, with 23 questions asked from men and 24 from women.

I’m not sure why this session was so different from the Friday session that Joe reported on, but possibly relevant factors are that there were more female speakers – 5 out of 8 vs. 1 out of 8 on Friday, and that the audience was smaller – about 40 vs. about 60 on Friday. I also kept track of who had their hand up, both Friday and Sunday. In both cases, when women did raise their hand, they were usually called on. In the Friday session, women weren’t raising their hands.

This indicates that what’s going on here is that often, but not always, women feel less comfortable asking questions in question periods than men do. I’m sure there’s a complex constellation of reasons for this, so I thought I’d ask women who are reading this discussion to weigh in: if you have a question but you decide not to ask it, why not?

I’ll go first: for me there are a few different possible reasons, including

1) I become irrationally worried that the question was already answered in the talk, or that I didn’t understand something fundamental, and that I’m going to look stupid by asking the question

2) I worry that my question is too confrontational

3) Lots of people have their hands up and I decide that my question is probably not important enough

These are in decreasing order of magnitude/how often I feel they come up. I’m curious if women’s reasons for not asking questions differ in any interesting way from men’s reasons?

Thanks for posting and starting some discussion on this, Joe. I’ve actually been planning on writing a blog post about this myself for the LSA’s student committee blog when it gets up and running.

I’ve been thinking about this more since the summer institute when there was lots of buzz about it, probably due to Stephanie Shih’s data (although I’ve been personally aware of the phenomenon for as long as I’ve been attending talks). One response was that people started saying/tweeting things like “we really encourage women to ask questions!” While it was good to see this unequal representation being acknowledged, it’s not the case that women simply need more encouragement to ask questions (if this was the case, the issue would be solved already).

As Claire and others have said, there’s a complex set of reasons that are making men more likely to ask questions. I don’t think it’s going to be overcome in any simple manner.

For some more data, I’ll follow Claire and give things that usually come up for me in hesitating to ask questions. They are similar to hers.

1) worrying that the question was already answered in the talk and I somehow missed it

2) at a talk outside my primary area of expertise – knowing I’m not an expert and not feeling qualified/my question might not be considered relevant by experts

3) I already asked a question at some other talk in this session/there are a lot of other hands/I’ve talked to the speaker already, etc.

I have a hypothesis that the reasons men and women hesitate to ask questions might not be totally different. The difference comes from men being more likely to dismiss/ignore the hesitation and ask anyways and women being more likely to consider the hesitation fully and not ask (hypothesis based on intuition and anecdotal conversations). Again, there are many reasons for this, resulting from everyone’s lifetime of gendered experiences.

Thanks Ivy – lots of valuable stuff here, and great to hear about your initiative. I agree with your analysis of the situation. We’ve had a fair bit of discussion in our department in the past about the things that keep people from asking questions in general, and the list is pretty similar. We have an internal document about this that I’m in the process of trying to get cleared for external distribution. I have to say that the gender issue is a new topic for me, and it’s the first time I’ve thought about holding back in questions because I am a man, and biasing my selection towards women. So that’s what gives me some hope that just raising awareness may actually lead to an amelioration of the problem. *But* that’s just my speculation… (I’ll go back to being quiet now).

Hello, I’m a visitor arriving from Language Log – very interesting topic, and thank you very much!

@Claire – shall we also query the purpose of the one who is asking? Is it to acquire knowledge (“In slide 14, does the graph refer to XYZ or ABC?”)? Or is it to share knowledge (“Have you considered the implications of Smith, Jones 2014a in your conclusions?”)?

Assuming that some portion of questions belong to the latter category, then perhaps some women are concluding through experience that their sharing of knowledge is less likely to be acknowledged anyway (as per Angelika’s first point) – and as such do not bother to share.

I’m not a linguist (only recreationally) but I work in underwater acoustics so I have had many years now of being a female scientist in a male-dominated field. I wanted to throw in a comment about reasons for not asking: my list is similar to Ivy’s #1 and #2. But what I try to do to counteract this tendency is to remind myself that men ask questions in those categories all the time and no one really cares in the long run. For #1, the audience looks a bit peeved and thinks, GEEZ, wasn’t he listening – but they immediately forget about it, and for #2, there are many others in the audience who are outside of their area of expertise who won’t bother to ask the question but will learn from the answer. Remember that the speaker often enjoys explaining some basic premise of their work, so everyone comes away happy.

Also in my field there are many more junior women than senior women. I am mid-career and not usually a question-asker myself (see Ivy’s reason #1). But at the last conference I attended (a smallish Canadian one where I knew most of the participants), I challenged myself to ask a question, any question, of every female speaker – so that it wouldn’t be a case of only older men asking questions of a junior woman (which can feel a bit confrontational at times especially at your first few conferences). It was an interesting exercise for me, who generally hates asking, and for the speakers, who were usually happy to answer, and hopefully learned something from answering and counted it as a positive experience. So I think this will be my new “thing”… one way to maybe make conferences a bit less intimidating for the next generation of female scientists. And also to normalize (for both me personally and the community at large) the idea of women asking questions as well.

The discussion of questions reminds me of past work on gender imbalance in professional settings on one hand, and on gender-linked differences in the use of questions on the other. I’m thinking especially of Cecilia Ford’s analyses of faculty meetings from a CA perspective (e.g. Women Speaking Up, 2008). I suspect that there may be other work in sociolinguistics or discourse analysis that is equally or even more directly related to formal question and answer sessions. I wonder if COSWL doesn’t have a formal set of resources (though I don’t see anything on the LSA web site).

It is also important to distinguish between the % that raise their hands to ask a question, and the % that get called on to actually ask that question. It is my impression that women’s hands are much more likely to be ignored than men’s. I should add that I have retired, and I would be delighted to be told that this is no longer true!

I am also not a linguist, but a women electrical engineer who, since the 1980s, has worked professionally in the field of electrical engineering. I was also in the first group of women to graduate from the Royal Military College of Canada in 1984. Currently, I work in Silicon Valley.

I, in fact, have always asked questions, both at conferences, in the classroom and in business meetings at work.

My observations about asking questions in conferences:

As a woman asking a question in a high visibility setting, you stick out. I’ve felt that there is an expectation that as woman I need to use a delivery style tends toward a “male” style. Direct, concise, clearly spoken, and no use of qualifier terms like “I think”. Those are the expectations. I’ve sensed that without this, I would be written off by many in the audience. Even when using this concise style, my observation as a women is that I am expected to not talk for too long, as it would be deemed that I am taking the floor from men.

My observations about asking questions in the classroom:

In classrooms: As a woman question asker in an engineering classroom context, I have sensed that I am not taken seriously by many professors. Sometimes, when a professor does not understand a question, I have observed there is then a tendency to quietly note that the student (me) doesn’t know what they are talking about. I suspect, but cannot prove, that women are more vulnerable to this type of judgment than men. Women might sense this vulnerability and therefore avoid the judgment by not asking questions. I have actually had classmates whistle when I asked a perfectly valid question about an advanced math approach. It was obvious enough that the professor in charge had to verbally discipline the class to stop this behavior. I’ve also had a not very competent professor call me a “trouble maker” for asking a perfectly valid question in a class. More subtle forms of these behaviors, communicating a need for women to be silent in class, are not that uncommon.

In business meetings at work:

It is my experience as a woman engineer in Silicon Valley (admittedly not linguistics with a near even gender ratio), where the workforce is almost all male, that in business meetings it is often impossible to even finish a sentence without being interrupted by a male colleague. For some reason, the culture in Silicon Valley has devolved to the point that young, often quite inexperienced mostly male engineers and computer scientists frequently overtalk their female coworkers. It is common for the technical contributions of women to be stolen outright by men.

I think recommendations from the likes of Sheryl Sandberg and others saying that women need to be coached to be more confident and ask more questions are quite naïve.

I would also add that I have worked with men from cultures where listening is more highly valued than in Silicon Valley. For instance, listening in Japanese and Native American cultures is more highly valued. There is a discernible difference and greater ease communicating with these men as a woman, by comparison. So, I think the difficulty that women experience communicating in a European or a European North American setting is a response to the accepted and expected dominance, and lack of value of listening, rather than speaking, by men over women, in our culture.

It is my observation that even people who think they are very open and forward thinking on this issue do not fully recognize the dynamic at work. Little is every done about it. When someone points out that all is not well, or that an organization has a communication problem, there is almost always huge pushback and denial.

Actually, the whole “Lean In” campaign, at least as it was originally pitched, is a form of social denial on this issue.

Interesting discussion. I can’t comment on the causes, but in looking for solutions, I’d suggest that we focus much earlier in the pipeline than in academic conferences. This reminds me of the problem with diversity in recruiting for PhD programs or faculty positions — the problem starts much earlier, in middle school or before. In that area, we can make more of a difference by working on the pipeline at an earlier stage. Similarly, if we value diverse participation in this kind of academic discussion, then we can do more to address it in lower-stakes settings in our classes, reading groups, practice talks, etc. etc. And we can talk more explicitly about why we value it, how to do it effectively, etc. We occasionally offer training in how to be an effective poster presenter, but how about if we give training in how to be an effective poster visitor? That’s a lower-stakes situation, and perhaps one that could yield more useful interaction?

Of course, all this presupposes that we value these things and want to see everybody doing it. An alternative view could be that it is so much self-preening and a waste of everybody’s time. Just because we do it, doesn’t mean it’s a good thing.

@Colin Phillips

I’m not sure what you mean by the “pipeline”.

There is no pipeline problem in terms of women graduating with advanced degrees in linguistics, engineering, science, medicine, etc. You name it. Women are graduating with degrees in those areas.

Actually, in almost all academic STEM fields, there is no pipeline problem at all. You can have a look at various labor statistics and studies from the Economic Policy Institute and the IEEE which indicate that we absolutely do not have a pipeline problem in STEM fields. Instead, what these studies indicate is that we have a substantial STEM surplus, with over half of all people graduating with STEM degrees not finding jobs in STEM at all. The rate of STEM unemployment is higher for women than men.

That might be one of the reasons why work culture has become so severely degraded and hyper competitive. There are simply too many people competing over too few jobs and for too few advancement opportunities.

Sure, you can drum up a few “big data”, “digital marketing” or “cloud computing” recent success stories, but you have to consider these against layoffs at companies like GE, Microsoft, Avago/Broadcomm, IBM, HP, Oracle, Intel, Disney, Sony, Citrix, Qualcomm, etc.

Many of the decision makers, who could implement policies to improve the work climate, became established in their fields thirty or more years ago. Often, it seems as if decision makers have no idea of the work climate (academic and otherwise) that younger people are contending with.

In electrical engineering and computer science, I’ve seen the work climate for women and other minorities slide backward in the last fifteen years. This correlates strongly with various policies put in place in the late nineties that led to a surplus of STEM graduates and professionals.

So again, the “pipeline” problem cannot be used to explain the silence of women at conferences, and in other professional settings.

Sorry, this was not the point of my comment. Women are not underrepresented in this field to anything like the degree found in some other STEM fields. My point was that we can perhaps make more of a difference by addressing a concern earlier in the process. If there’s a male dominance in the discussion at big conferences, perhaps that’s also there in discussions at our home institutions, and we can do more to address the issue locally. At home, we know the individuals, have more ability to shape the atmosphere, much more ability to follow up, explicitly discuss, etc.

Here at Maryland, we already do some things to explicitly encourage everybody to speak up, as I’m sure people do in other places. We’ve been exploring some new strategies as part of our Winter Storm workshop last week and next week. But this discussion makes me realize that there’s more that we could do. There’s a long history of training academics in one-way communication, but we give almost zero guidance in two-way communication. That’s not so good.

@Colin

I definitely agree that employing strategies to encourage effective two way communication, active listening, and concise, polite speaking would be effective toward allowing a greater cross section of people to speak up in conferences and in other academic and business settings.

I’m coming a bit late to the discussion, but I wanted to thank Joe for initiating it here and all the commenters for their useful perspectives.

I was at both of the LSA sessions mentioned above — the phonological learnability one, and the phonology/morphology/lexicon one. The very different ratios of male and female questioners reported by Joe and Claire is quite striking. But I think this might be partially due to the topics of these sessions (a factor we can also see in a comparison of the ratios of male and female speakers in those sessions, as Claire has pointed out). While there are certainly women working on learnability, my impression is that they are much fewer than one would find on average in a randomly chosen sample of phonological subfields. So I’m guessing there were fewer women in the audience in the learnability session who had thought deeply about the issues at hand — not that this is by any means a prerequisite for being in a position to ask a question, but when you’ve thought about something a lot already, questions are probably more likely to occur to you.

As far as what we can do to train students early on to be willing to ask questions, I still remember something Kyle Johnson said about Friday Colloqs when I was a grad student: he said he always tried to come up with a few questions anytime he was listening to a talk, whether he actually asked them or not. This might be something we could all encourage {our|fellow} students to do. Thinking of things to ask is itself a non-trivial skill, and it has to come before the asking of the questions themselves. And thinking of questions during a talk is a good way to encourage oneself to engage with the ideas more deeply, anyway.

For those who like numbers

Does anybody know whether there are empirical studies that inquire on other factors influencing gender bias? There may be reason to assume that the amplitude is group-specific, depending on factors such as education, age, socio-professional category or culture.

Here are some numbers relevant to the discussion and concerning a group of phonologists, i.e. the board of the Manchester Phonology Meeting, which is made of 25 members out of which 11 are women (see the Mfm website). Maybe Laura Downing (who actively promoted the gender issue at the last Mfm board meeting based on numbers) has already reported the situation of the upcoming Mfm. Once the theme of the special session was agreed upon, board members suggested names for invited speakers. This produced a candidate set of 16 men and 4 women. Then the board voted and the top three names were invited. The result, as you may see on the Mfm website, is two invited women and one man.

Maybe somebody can do the math to calculate what the probability is for this result, assuming all other things being equal.

Of course there is nothing much to be drawn, statistically speaking, from one venue (although I have seen quite a few cases where people make bold statements on the basis of n=1), but maybe somebody who is on the Mfm board can gather (or has already gathered) relevant numbers from previous years (Laura?).

In any case, the 2016 venue suggests that phonologists (more precisely, Mfm board members) have an anti-male gender bias. This should maybe be watched.

Tobias – thanks for participating in this discussion. Let’s imagine that your hypothesis is correct – that the mfm board’s decision was influenced by a bias to prefer female to male invited speakers for this year’s conference (I agree that a longer term study, like those already presented in the updates to my original post, would really be needed to confirm a bias). Why might they have such a bias? It’s possible that they felt like they wanted to partially correct for an earlier bias toward male speakers (the one that has been documented, modulo a possible age confound). I’d like to speculate that the bias toward male speakers is the result of a culturally ingrained unconscious bias, while the possible bias towards female speakers is the result of conscious decision making. I think it’s very important in discussions like these to recognize that these biases can be unconscious, so that it’s clear that we are not accusing one another of conscious sexism (or racism). I’m also of the opinion that making conscious choices to make the outcome of these decision processes more balanced is a good practice, though I am aware that this is controversial (see debates over affirmative action).

Clearly, different people are going to weight various considerations differently in making decisions such as these, and I don’t think anyone would want to have us as conference organizers adopting policies that some group of us would see as unfair. Here is a procedure that I know has been applied with some success in other contexts, and which sounds kind of similar to what may have happened in the mfm decision. When a decision has to be made in which historically underrepresented groups are competing with historically overrepresented groups, we can remind ourselves of what the data are (representation of different groups in the general candidate pool, statistics on past choices), and then each person can vote taking these and other factors into consideration.

Humans don’t choose other humans at random. But to answer the purely numerical question: from a sample of 16 males and 4 females, choosing 3 humans at random yields the following numbers:

3 men, 0 women: 50%

2 men, 1 woman: 42%

1 man, 2 women: 8%

0 men, 3 women: 0.3%

Obviously, the initial sample of 16 men and 4 women is not random. Humans do not choose other humans at random.

On the topic of general imbalances in talking time between men and women, Larry Hyman pointed me to Janet Holmes’ chapter in the Language Myths book, which is summarized here: http://www.pbs.org/speak/speech/prejudice/women/

“I found the same pattern analysing the number of questions asked by participants in one hundred public seminars. In all but seven, men dominated the discussion time. Where the numbers of women and men present were about the same, men asked almost two-thirds of the questions during the discussion.”

“There is abundant evidence that this pattern starts early. Many researchers have compared the relative amounts that girls and boys contribute to classroom talk. In a wide range of communities, from kindergarten through primary, secondary and tertiary education, the same pattern recurs – males dominate classroom talk.”

One interesting question that the MFM invited speaker example raises concerns the makeup of the slate of candidate speakers (16 male, 4 female) vs. the outcome of the vote (1 male, 2 female). The evidence for a potential anti-male bias rests on the assumption that all candidates on the initial list were equally strong candidates. But given the number of research studies showing that male candidates and female candidates with comparable (or even identical) records are evaluated differently (see, e.g., the Moss-Racusin et al. 2012 study in PNAS reporting that the same CVs were judged more highly when male names appeared at the top than when female names appeared at the top, by both males and female evaluators), we can’t discount the possibility that women may need to be exceptionally strong in order to even come to mind as potential speakers.

Ellen, this kind of thing has been observed also in computer science: women on GitHub whose gender is not apparent from their profile have their contributions to projects accepted more often than men, suggesting that they have to be better coders in order to survive in the community. (Women whose gender is apparent from their profile have their contributions accepted more rarely)

http://arstechnica.com/information-technology/2016/02/data-analysis-of-github-contributions-reveals-unexpected-gender-bias/

Now in comedy form:

http://www.theallium.com/science-life/female-scientist-treat-presenting-poster-listening-plenaries-male-speakers/

Thanks Joe for pointing us to this blog post.

I wanted to raise another observation, from the NECPhon a few years ago in New York. Many of us were pleased to see a gender balance among the speakers that year. But then I noticed that for every female speaker except one, someone jumped in to answer her questions for her after her talk. This did not happen for the male students. In fact, there was one person I noticed who jumped in to answer a female student’s questions, but held back and did not do so for a male student. (I don’t mean to put blame on particular people; in fact, I jumped in to answer questions for one of my students, before noticing this pattern. Unconscious bias is, by definition, unconscious and unintentional.)

Personally, one thing that motivated me to start asking questions at conferences was having organized a conference. I noticed that in choosing people to invite, we gave preference to those speakers who would “discuss” more effectively. So I decided I wanted to fit into that category! Asking and answering questions is a skill that needs practice, and I’m now much better at it than I was when I started, and I think the more opportunities students have to practice, the more they’ll be willing to speak up in scary situations.

@Colin: This is not just an earlier-in-the-pipeline issue. If you’d like, I’d be happy to chat at some point about some examples in our department of how unconscious bias inadvertently creeps in.

Thanks for these comments Naomi – yet another behavior we men will want to check for bias…

By the way, there’s a nice piece on these issues in neuroscience, where an initiative to keep track of speaker invitation rates has started a similar discussion:

http://www.nytimes.com/2016/09/06/science/gender-bias-scientific-conferences.html?smid=tw-share&_r=0

I might be misunderstanding what you mean, but when you say “we men will want to check for bias” do you mean to suggest that only men are biased in this way? The literature I’ve seen and heard talked about suggests that everyone — both men and women — exhibit similar biases.

Thanks for the correction Naomi!

A much-needed exploration of voices that have long been underrepresented. Highlighting the role of women in phonological discourse not only enriches the field but also challenges historical imbalances and paves the way for more inclusive and diverse linguistic scholarship.

Access Assistant