One of the other great things about the ASA is the book exhibit, which allows for all sorts of new ideas to bounce around in your head. I picked up Steven Johnson’s The Ghost Map, and inhaled it in two days. It is a near-perfect book for urban sociology. It has everything: a deadly disease (cholera) a tale of scientific inquiry triumphing over myth (social research over the ‘miasma’ hypothesis), compelling protagonist (the premiere London anesthesiologist who uses ‘shoe-leather’ and sociological research to solve the riddle, and a young priest who uses his neighborhood-level knowledge for crucial assistance), and maps!

It is the story of the 1853 cholera outbreak. Deaths were assumed to have something to do with bad air (‘miasma’), and that theory led to questions over elevation, leading researchers to believe that inner-city dwellers at once were to blame for the miserable conditions they were in, but also to explain how elites who lived in places like Hampstead were spared. (The result of the 19th Century outbreak was about 1000 London souls–in proportion, greater than the deaths from 9/11.) In truth, the communities at higher elevations:

tended to be less densely settled than the crowded streets around the Thames, and their distance from the river made them less likely to drink its contaminated water. Higher elevations were safer, but not because they were free from miasma. They were safer because they had cleaner water. (p. 102)

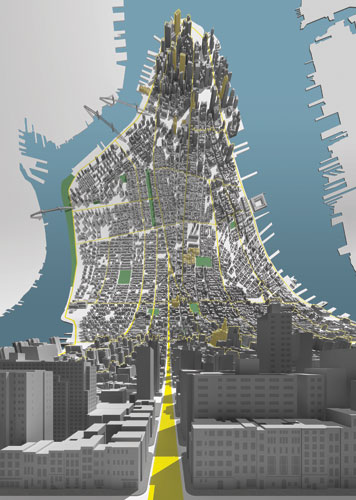

There are all sorts of lessons for students within. Examples include: the Durkheimian specialization of roles in cities (and particularly around the problem of waste/’night-soil’) (p. 1-5), social prejudices of class and race affecting research (p. 133), local knowledge (inter alia, p. 146-7), the interviewer effect (p.155), urban planning gone askew (p. 120), how a bad theory can frame research questions (p. 165), city planning and infrastructure (inter alia, p 18), urban development as a mixture of collective action and individual choice (p. 91), urban traumas (p. 33), the power of local knowledge and autodidacts (p. 202 and 220), mistakes over correlation and causation (p. 101), the ramifications for global cities wherein over a billion squatters live today (p. 216), and the effects of powerful visual representations of social data (p. 193-97). It has given me a few more ideas to the festival project. (You can listen to the author talk about it here.)

There are all sorts of lessons for students within. Examples include: the Durkheimian specialization of roles in cities (and particularly around the problem of waste/’night-soil’) (p. 1-5), social prejudices of class and race affecting research (p. 133), local knowledge (inter alia, p. 146-7), the interviewer effect (p.155), urban planning gone askew (p. 120), how a bad theory can frame research questions (p. 165), city planning and infrastructure (inter alia, p 18), urban development as a mixture of collective action and individual choice (p. 91), urban traumas (p. 33), the power of local knowledge and autodidacts (p. 202 and 220), mistakes over correlation and causation (p. 101), the ramifications for global cities wherein over a billion squatters live today (p. 216), and the effects of powerful visual representations of social data (p. 193-97). It has given me a few more ideas to the festival project. (You can listen to the author talk about it here.)

In another retelling of London, Penguin Books is offering up a ‘We Tell Stories’ series, wherein authors are asked to tell a story using the first line of a classic, using new technology in some way. Charles Cummings wrote ‘The 21 Steps‘ (spinning off of James Buchan’s The 39 Steps), which is a fun romp. It is a detective story that uses Google Maps to help tell the tale. Here is the background of its creation.

And last, here is a link to ‘The Hand Drawn Map Association.’

(Justin A. has sent along a nice set that includes pictures of Northampton’s old, recently torn down mental hospital: here.)

(Justin A. has sent along a nice set that includes pictures of Northampton’s old, recently torn down mental hospital: here.)

Nathan Glazer pens a

Nathan Glazer pens a

There are all sorts of lessons for students within. Examples include: the Durkheimian specialization of roles in cities (and particularly around the problem of waste/’night-soil’) (p. 1-5), social prejudices of class and race affecting research (p. 133), local knowledge (inter alia, p. 146-7), the interviewer effect (p.155), urban planning gone askew (p. 120), how a bad theory can frame research questions (p. 165), city planning and infrastructure (inter alia, p 18), urban development as a mixture of collective action and individual choice (p. 91), urban traumas (p. 33), the power of local knowledge and autodidacts (p. 202 and 220), mistakes over correlation and causation (p. 101), the ramifications for global cities wherein over a billion squatters live today (p. 216), and the effects of powerful visual representations of social data (p. 193-97). It has given me a few more ideas to the festival project. (You can listen to the author talk about it

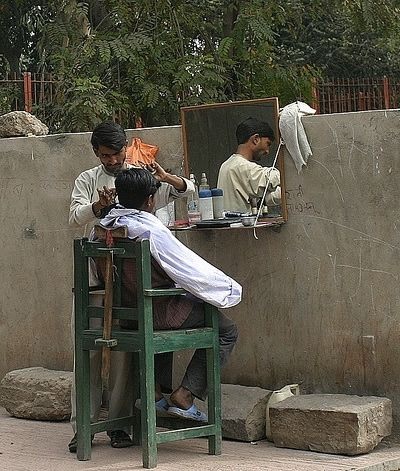

There are all sorts of lessons for students within. Examples include: the Durkheimian specialization of roles in cities (and particularly around the problem of waste/’night-soil’) (p. 1-5), social prejudices of class and race affecting research (p. 133), local knowledge (inter alia, p. 146-7), the interviewer effect (p.155), urban planning gone askew (p. 120), how a bad theory can frame research questions (p. 165), city planning and infrastructure (inter alia, p 18), urban development as a mixture of collective action and individual choice (p. 91), urban traumas (p. 33), the power of local knowledge and autodidacts (p. 202 and 220), mistakes over correlation and causation (p. 101), the ramifications for global cities wherein over a billion squatters live today (p. 216), and the effects of powerful visual representations of social data (p. 193-97). It has given me a few more ideas to the festival project. (You can listen to the author talk about it ![[walls.jpg]](http://bp3.blogger.com/_qXoW9B_AHE4/R2fDP3b769I/AAAAAAAAACY/5xyMK-qOCHk/s1600/walls.jpg)