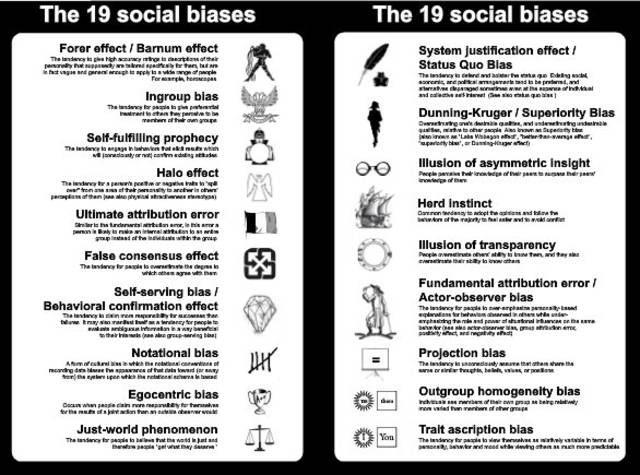

I love using horoscopes the first day of class to talk about how we perceive the world around us. I run a variation of the Forer Demonstration. I use the exercise in conjunction with a story about two septuagenarian Finnish Twins (who die on the same day, on the same stretch of road, on bicycles, a few hours apart from each other) and the numerology of 9/11 to talk about the different frameworks we use to analyze the world, and how sociology is different. This year, I’m mulling over Gerd Gigerenzer’s new book, Gut Feelings: The Intelligence of the Unconscious, as a way to build up to the notion of habitus. (See Scientific American‘s take on horoscopes.) I like it, but it doesn’t address at all how people arrive at their ideas and opinions, something that is done so simply in one of my favorite essays, Twain’s Corn-Pone Opinions. He recalls a maxim he overheard by a slave preacher: “You tell me whar a man gits his corn pone, en I’ll tell you what his ‘pinions is.” (Corn-pone is another word for cornbread, but it was also used as a derogatory term for a kind of country bumpkin, adding a different layer to the essay.) Well, it’s a great essay to think through Mills’ Sociological Imagination. Twain (to the right, with the ghostly Nikola Tesla) writes:

I love using horoscopes the first day of class to talk about how we perceive the world around us. I run a variation of the Forer Demonstration. I use the exercise in conjunction with a story about two septuagenarian Finnish Twins (who die on the same day, on the same stretch of road, on bicycles, a few hours apart from each other) and the numerology of 9/11 to talk about the different frameworks we use to analyze the world, and how sociology is different. This year, I’m mulling over Gerd Gigerenzer’s new book, Gut Feelings: The Intelligence of the Unconscious, as a way to build up to the notion of habitus. (See Scientific American‘s take on horoscopes.) I like it, but it doesn’t address at all how people arrive at their ideas and opinions, something that is done so simply in one of my favorite essays, Twain’s Corn-Pone Opinions. He recalls a maxim he overheard by a slave preacher: “You tell me whar a man gits his corn pone, en I’ll tell you what his ‘pinions is.” (Corn-pone is another word for cornbread, but it was also used as a derogatory term for a kind of country bumpkin, adding a different layer to the essay.) Well, it’s a great essay to think through Mills’ Sociological Imagination. Twain (to the right, with the ghostly Nikola Tesla) writes:

The outside influences are always pouring in upon us, and we are always obeying their orders and accepting their verdicts. […] A man must and will have his own approval first of all, in each and every moment and circumstance of his life — even if he must repent of a self-approved act the moment after its commission, in order to get his self-approval again: but, speaking in general terms, a man’s self-approval in the large concerns of life has its source in the approval of the peoples about him, and not in a searching personal examination of the matter. Mohammedans are Mohammedans because they are born and reared among that sect, not because they have thought it out and can furnish sound reasons for being Mohammedans; we know why Catholics are Catholics; why Presbyterians are Presbyterians; why Baptists are Baptists; why Mormons are Mormons; why thieves are thieves; why monarchists are monarchists; why Republicans are Republicans and Democrats, Democrats. We know it is a matter of association and sympathy, not reasoning and examination; that hardly a man in the world has an opinion upon morals, politics, or religion which he got otherwise than through his associations and sympathies. Broadly speaking, there are none but corn-pone opinions. And broadly speaking, corn-pone stands for self-approval. Self-approval is acquired mainly from the approval of other people. The result is conformity.

Then, there is Proust’s In Search of Lost Time, in which he writes of habit (which is not directly habitus, yes, yes):

As a rule it is with our being reduced to a minimum that we live; most of our faculties lie dormant because they can rely upon Habit, which knows what there is to be done and has no need of their services.

I love using horoscopes the first day of class to talk about how we perceive the world around us. I run a variation of the

I love using horoscopes the first day of class to talk about how we perceive the world around us. I run a variation of the