By Sofia Pitouli

“Purity of writing is purity of the soul” (طهارة الكتابة هي نقاء الروح.). So states an old Arabic saying that points to the importance of writing, and especially of beautiful writing, in Islamic culture.[1] Under the third successor of the Rashidun Caliphate, Caliph Uthman (r. 644-56), the revelations of Prophet Muhammad, once transcribed unsystematically on various materials, were written in the Qur’an, the Muslim sacred book. Afterwards, the Caliph’s representatives sent the Qur’an out to various Islamic lands to expand the Muslim faith. In these Qur’an manuscripts, one encounters a beautifully written language. Muslim faith expressly opposes the use of figural visual vocabulary, such as humans and animals in religious arts. These include Qur’an manuscripts and mosque decoration. This opposition led calligraphy to occupy an integral part in the decoration of Islamic works of art and objects. As a result, sophisticated and elaborate calligraphic script exists in Islamic manuscripts, textiles and metalwork, serving both as inscription and ornamentation.

Fig. 1. Brass Basin, 1247-49, Ayyubid period, probably Damascus, Syria, brass inlaid with silver, Freer Gallery of Art, F1955.10

The angular script used to ornament Islamic art and architecture is spaced not according to the exigencies of grammar, but rather for aesthetic reasons.[2] From early on, Arabic letters such as alif and leem (ا ل) took aesthetically pleasing forms, decorated with flowers, usually palmettes, or with elaborate letter trains as in a 13th-century brass basin from Syria (fig.1). In addition, inscriptions on surviving Islamic secular objects illustrate the Arabic cursive letters with human and dragon heads (fig.2).

Fig. 2. Copper Alloy Drum, 12th century, Artuqid Dynasty, Turkey, copper alloy, ht. 25 in, Turkish and Islamic Arts Museum, Istanbul

The inventiveness and creativity of the Muslim scribe within the set boundaries of the faith were endless. It is through this flourishing artistic repertoire that expressive calligraphy turns into something beyond writing, into a drawing. This essay will explore Lalla Essaydi’s use of Arabic calligraphy as drawing in her photograph, Les Femmes du Maroc #14 (Fig. 3). Essaydi uses abstract calligraphy as a feminist response to the exclusion of women from cultural production in Arab culture and applies it to the female body as a defensive screen. In order to explore calligraphy as drawing, I consider the work of art from three different angles: (1) the gender implications of the artist’s use of calligraphy (2) the implications of Arabic script for diverse audiences familiar or unfamiliar with the language; (3) the effect calligraphy has on the composition of the photograph.

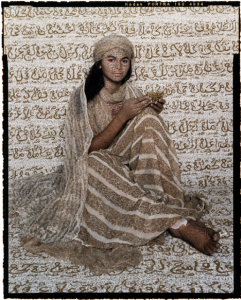

Fig.3. Lalla Essaydi (Moroccan, born 1956), Les Femmes du Maroc #14, 2005, Photograph: C41 print mounted on aluminum. 34 1/8 in x 40 1/8 in x 1 1/8 in. AC 2007.13

Lalla Essaydi’s Les Femmes du Maroc #14, created in 2005 and recently on view at the Mead Museum at Amherst College, is an amalgamation of two distinct mediums: photography and drawing. The bare skin of the female model who occupies the unidentified space is decorated with calligraphy. Likewise, the entire surface of the backdrop and environment — except the female body adorned in minuscule calligraphy— is covered by what appears to be Arabic cursive writing. The ubiquitous calligraphy on the body and other surfaces reframes the original function of calligraphy. The artist’s use of calligraphy recalls only to renounce its conventional use as a literary source and the gender associations it traditionally reflects in the Muslim community.

Throughout history, calligraphic writing has had strong associations with the male gender. All Muslim men from North Africa to India are taught how to write calligraphy, while numerous Islamic rulers are known for excelling in it. Occasions of women learning calligraphy in the past existed, but rarely. Despite their skill, women never practiced calligraphy as a profession. This inaccessibility associated with calligraphy triggered Essaydi’s inspiration. Lalla Essaydi in her series Les Femmes du Maroc, challenges gender associations regarding calligraphy by performing pseudo-Arabic cursive writing on the entire scene and on the model’s body—the body of a woman.

Essaydi further challenges gender implications embedded in calligraphy via the material she uses. Muslim calligraphers traditionally prepared the ink themselves. There were numerous trade secrets in the making of black, brown, golden, or other colors from soot, ox gall, and various ingredients.[3] Essaydi, instead of using the traditional ink, uses henna. Henna has always been associated with feminine experience. It is a material that signifies the most important events in a woman’s life. Henna in Morocco, the artist’s native country, decorates the skin of young girls when they reach puberty, marking the girl’s passage into womanhood. Women are once again painted with henna when they get married. Henna functions as an enhancement of the bride’s charm. Finally, henna is drawn on pregnant women, especially while bearing the first child.[4] Traditional henna tattooing is applied to the female body in the form of elaborate, intricately drawn designs. In Essaydi’s Les Femmes du Maroc #14, the body of the woman is covered in minuscule Arabic calligraphy instead of designs. However, the use of henna as “ink” provides an important symbolism, as it is not normally used for calligraphy.

In her interview “In Search of Beauty in Space,” Essaydi explains the origins of her interest in calligraphy. Her inability to express herself through text as accurately as she could visually created an enormous fascination for her, leading to the use of calligraphy as a visual element.[5] Although writing is associated with “meaning,” Essaydi uses the visual qualities of writing to illustrate meaning. Her approach to writing as a visual element with meaningful symbolism further denotes the role of calligraphy as a drawing in her Les Femmes du Maroc #14. The handwritten nature and almost excessive, allover composition of the Arabic calligraphy—elements that make it seem more like drawing—suggest an autobiographical narrative. Yet, an autobiographical message would be untraditional since calligraphy is associated to the Qur’an; thus, Essaydi challenges the Muslim culture and gender traditions even further. The presence of calligraphy directs the viewer to explore and experience the artist’s line or brushstroke, as one expects in any “traditional” drawing. The artistic line expressed by her unique handwriting causes each letter form to suggest a certain feeling, dictated by the lightness or pressure of the pen as it touches the surface.

Fig. 5. (detail) Lalla Essaydi (Moroccan, born 1956), Les Femmes du Maroc #14, 2005, Photograph: C41 print mounted on aluminum. 34 1/8 in x 40 1/8 in x 1 1/8 in. AC 2007.13

Fig.4. (detail) Lalla Essaydi (Moroccan, born 1956), Les Femmes du Maroc #14, 2005, Photograph: C41 print mounted on aluminum. 34 1/8 in x 40 1/8 in x 1 1/8 in. AC 2007.13

No letter is the same and therefore they evoke something from within, individuality. Each letter trail is shaped unexpectedly based on the artist’s handwriting and momentary experience. For instance, letters such as ا ل ن ص س are exaggerated, attaching their parts with letters from other rows and creating innovative forms. For instance, the ل trains turn into a spiraling shape while parts of the letter touch other characters (fig. 4). The curves of the س are enlarged compared to the letter’s original depiction in Arabic texts and manuscripts, denoting the presence of a personality hidden behind these letters (fig. 5). Parts of some curvilinear letters are so exaggerated that they resemble tear drops (fig. 6). The letters turn into fantastical forms that do not exist in the Arabic alphabet. The shaping of letters occurs from the combination of the artist’s unique handwritten line and expression. The Arabic characters on the backdrop constantly shift. The background is composed of narrow and long lines of minuscule script, with thin organically curved, larger Arabic script running over it. The crowded nature of the Arabic characters makes them appear as gestural shapes, moving around in all directions and existing in flux.

Fig. 6. (detail 1,2) Lalla Essaydi (Moroccan, born 1956), Les Femmes du Maroc #14, 2005, Photograph: C41 print mounted on aluminum. 34 1/8 in x 40 1/8 in x 1 1/8 in. AC 2007.13

The touch and trace suggest the emotions of the artist while engaging with her subject. The writing is created by an individual, not a machine that produces similar characters for everyone. The individuality and uniqueness of the characters create a visual vocabulary for Essaydi to calligraphically express her inner self and internal concerns. Drawing is born from an outward gesture linking inner impulses and thoughts to the other through the touching of a surface with repeated graphic marks and lines.[6] For Essaydi, this outward gesture is writing. Through writing, she externalizes her inner thoughts. Yet, she manages to keep the viewer in set boundaries as well, as I will explain. As drawing throughout time was traditionally considered a preparatory medium, the calligraphy on the surface performs similarly as a way to note these ideas or concerns of the artist. Essaydi’s calligraphy mimics elements of abstract works of art. Abstract works aim to make the viewer contemplate what they see. The feelings of the artist are hidden but the visual vocabulary suggests emotion. Calligraphy in #14 becomes an abstract form of expression with tremendous visual symbolism, evident through the spontaneous and energetic gestures that displace the traditional literal function of writing.

Calligraphic education was a painstakingly long and difficult process. One had to sit in the proper way, holding the paper or parchment with the left hand resting on the left knee so that it could bend slightly under the movement of the pen; only in this position could the perfect rounds of the “letters with a train” be achieved.[7] Essaydi’s process of photograph production mimics the intense working environment associated with calligraphy. Yet, she challenges its monotony by including a social element. Essaydi and the models spend time together, building relationships and forming bonds with one another before she considers drawing on their bodies and eventually photographing them. In numerous interviews, the artist reflects upon the extensive process in which she and the female models engaged before she takes her photographs. Essaydi notes that they spend a tremendous amount of time writing on their bodies, an exhausting process since they cannot sit down, or they will ruin the calligraphy. The photoshoots also consume long periods of time: sometimes she only sleeps for three hours a day. However, the entire process, from the day they meet until the end of the photoshoot, is reminiscent of the traditional henna celebration events held by women for women. Essaydi’s process, material, and visual vocabulary reject the masculine connotations of calligraphy and its procedure to take on a new, feminine symbolism. The henna scriptures become a peaceful rebellion against the boundaries established by men for women within Muslim society. The combination of material and visual vocabulary challenge long-standing traditions in the Muslim community and the art world’s perspective regarding the relationship between calligraphy and drawing.

The idea of calligraphy as a personal expression is rooted to the history of modernism both in Europe and North African modern art. Essaydi is not the first artist to use Arabic calligraphy as drawing. The Hurufiyya (حروفية) movement, named after the word harf (حرف), or “letter,” and alluding to the medieval Islamic scientific study of the occult properties of letters,[8] was a Middle Eastern aesthetic movement in the 20th century. Arab artists used the beauty and complexity of Arabic calligraphy not only for its literary meanings, but as innovative visual styles. In some instances, calligraphy takes the shape of imaginative forms. Other times, words spread out on the surface and do not form coherent sentences. The abstractness of the calligraphy and its function not as literature but visual form highlights its role as a drawing. The artist guides the viewer to comprehend the meaning of the scripture. Arabic letters for someone educated in the Latin alphabet may be challenging. Arabic characters have utterly different shapes than the Indo-European alphabet. Furthermore, the Arabic cursive script reads from right to left, the opposite of the way all western alphabets and numerals are written. For the westerner, the Arabic script is a source of admiration but also of confusion. A person unable to read Arabic may feel as if they are kept on the outside while viewing Essaydi’s works, especially Les Femmes du Maroc #14, which develops an even more abstract version of Arabic calligraphy. The alphabetical characters turn into gestural marks and abstract shapes separated from their linguistic meanings, metamorphosing into a new visual vocabulary. This vocabulary becomes a veil of protection for the sitter.

In the entire photographic series “Les Femmes du Maroc,” Essaydi provocatively engages viewers with her own version of Moroccan women. These photographs maintain the pictorial composition of western Orientalist paintings.[9] Orientalism has always had a multiplicity of meanings, but the significant problem of Orientalist depictions is their naturalism, their normative tone. The word Orientalism originally has a wholly sympathetic ring: the study of the languages, literature, religions, thought, arts and social life of the East in order to make them available to the West, even in order to protect them from occidental cultural arrogance in the age of imperialism. Orientalism came to represent a construct, not a reality, an emblem of domination and a weapon of power. It lost its status as a sympathetic concept, a product of scholarly admiration for diverse and exotic cultures and became the literary means of creating a stereotypical and mythic East through which European rule could be more readily asserted.[10] Essaydi bases her composition on the most well-known tropes of French Orientalist painting regarding the display of female subjects. She replaces fabrics linked to certain Eastern places and cultures due to their design or color with homogeneous textiles. She removes all male figures and resists the construction of her work for a male gaze. She creates an environment that questions the assumptions of western masculinity vis-à-vis women of the “East” and forms a space of creative transgression for the models and herself.

Fig. 7. Pierre-Auguste Renoir (French, born 1841-1919), Odalisque, 1870,

Oil on canvas, 27 ¼ x 48 1/4 in. National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC

In Les Femmes du Maroc #14, Lalla Essaydi references Pierre-Auguste Renoir’s Odalisque, dated 1870 (fig.7), one of the most renowned later Orientalist paintings of a reclining nude woman. As she explains in her essay “Disrupting the Odalisque,” Essaydi wants “the viewer to become aware of Orientalism as a projection of the sexual fantasies of Western male artists—in other words, as a voyeuristic tradition.” Here calligraphy draws a veil of protection over the reclining clothed female, one not so easily removable as the loose clothing in Orientalist nudes like the model in Renoir’s painting. The calligraphy over all the surfaces of the photograph creates an unidentifiable space that cannot suggest a location with sexually oppressive connotations for women, such as a harem. The woman is protected from the male gaze and removed from stereotypical assumption of her sexual availability through the direct calligraphy on her body as well as the background. The interplay between the graphic symbolism of calligraphy and its literal meaning is constantly questioned.[11] The ubiquitous calligraphy turns into an abstract set of lines and shapes for the western viewer unable to read Arabic. Instead, these abstracted drawings perform as a veil protecting the sitter in the photograph from the western stereotypical gaze when encountering these “exotic” women posed like a traditional odalisque.

Essaydi aims to protect women from the negative impact of male gaze in their public and personal lives. With the shift from admiration of the East to the ideology of Orientalism as imperialism, the lives of men and women in Arab societies changed. Rules men created for women became stricter, leaving them almost no freedom, precisely in order to protect them from the western gaze. When the West portrays Eastern women as sexual victims and Eastern men as depraved, the effect is to emasculate Eastern men, and to challenge the traditional values of honor and family. So Arab men feel the need to be even more protective of Arab women, preventing them from being targets of fantasy by veiling them. The veil protects them from the gaze of Orientalism.[12]

What is even more fascinating about this veil of calligraphy is that the woman of this specific photograph (#14) is also protected or veiled from the gaze of someone who can read Arabic, for example a man from her own culture. The texts alluding to Kufic calligraphy on the female body and the horizontal texts on the background are minuscule; the application of a literal meaning to these texts becomes almost impossible. The large calligraphy over the minuscule scripts adorning the surfaces of the photograph manipulate the viewer into thinking that the text is readable. However, when one aims to read it, it becomes an illegible script with only few legible words here and there, such as حمل (“pregnancy,” “to carry,” “to load”), اكبر (“the biggest,” also used when referred to God), من (“from”), موجود (“existing”) and حل (root of the verb “to dissolve”). Nevertheless, even the legible words are suggestive, since they do not form coherent sentences. The artist intentionally does not offer the viewer direct access to information; however, words and image are related to one another. Specifically, words such as موجود and حل are extremely important. The woman seems to exist (موجود) within the calligraphic veil, in a space protected by the Western and Arab men as well as their strict rules. In addition, the root of the verb حل (“to dissolve”) implies the existence of the woman within an environment where the strict rules imposed on women by men are destroyed, “melted down” as seems to have happened to the literal shapes and meaning of the letters. Yet, the photograph continues to be a mystery even for the Arabic reader. The scattered legible words only enhance the protection of the veil by suggesting all things traditionally forbidden to women, such as creativity, imagination, freedom of existence and expression, as well as feminine authority.

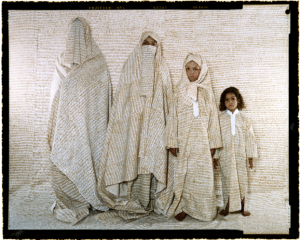

Fig. 8. Lalla Essaydi (Moroccan, born 1956), Les Femmes du Moroc: Revisited 9, 2005, Photograph: C41 print mounted on aluminum.

Not all of Essaydi’s photographs of Les Femmes du Maroc series develop an illegible script as a veil to protect the female sitter. Instead, she practices different methods of protection – always through the use of calligraphy – throughout her series of photographs. For instance, the background calligraphy of Les Femmes du Moroc: Revisited 9 (fig. 8) is not as blurred as in Les Femmes du Maroc #14. Minuscule calligraphy occupies the wall and floor of the photograph as in the Mead photograph. However, instead of abstract script, Revisited 9 features a well-defined and large horizontal script covering the background. Clearly, Essaydi does not aim to use the calligraphy as abstract forms here, instead using legible script in the shape of sentences to form a veil around and on the sitter. Protected from the male gaze, the female models of the Les Femmes du Maroc series represent their own small feminist movement. This feminist movement exists on its own terms, protected by the “veil” of the artist’s handwriting. The calligraphy creates a world where women exist independently. The male art of calligraphy is brought into the world of female experience from which it has traditionally been excluded, and in turn, the calligraphy used by the female artist excludes the male gaze from its world, through the use of calligraphy as a veil.

Fig. 9. Lalla Essaydi (Moroccan, born 1956), Converging Territories #30, 2004, Photograph: C41 print mounted on aluminum. 33 3/8 × 40 11/16 × 1 1/2 in. National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC

Essaydi’s photograph series “Converging Territories,” created a few years before Les Femmes du Maroc, further demonstrates the importance of calligraphy as protection. In Converging Territories #30 (fig. 9), Essaydi photographs women with the hijab in addition to the henna calligraphy on their face – the bare skin not covered by the rest of their costume. The photograph suggests the effect of Orientalism on the lives of women as well as protects them from the male gaze. Even the youngest girl in the photograph wears a long dress, while her face, hands, and legs are covered with calligraphy. The women following the young girl are progressively older and covered with more fabric, leading to the last female on the left, completely covered with clothes inscribed with calligraphy. The photograph depicts the oppression women experience as a result of western stereotypes and the strict rules created by Muslim men. In this photograph, the veil exists not only in calligraphy but also through textiles. A comparison between Converging Territories #30 and Les Femmes du Maroc #14 shows the change in calligraphic writing from one photograph to another. Calligraphy on Les Femmes du Maroc #14 becomes more complex and intricate. With the elimination of the hijab, the artist increases the intensity of the calligraphic veil on the body and the background, to replace the protection afforded by the fabric in the earlier series.

Essaydi captures a certain moment in time through her photographic lenses based on a prototype, the Orientalist painting. Traditionally drawing was the preparatory medium for painting; now it becomes a primary symbolic element in the photograph. Essaydi decomposes the stereotypical symbolism of the European odalisque. The model is posed according to Orientalist conventions, but the woman lays on the floor instead of a bed. The loosely worn traditional textiles are replaced with homogeneous, artistically inscribed textiles fully covering the Moroccan woman’s body. Essaydi plays with the male gaze as an art historical convention. She invites the male gaze into the photograph, only to exclude it through the use of calligraphy as a visual protection.

Along with calligraphy, color plays a tremendous role in the composition and its unity achieved through drawing. Before henna was applied on the scene, the wall, floor, clothes, headband, and pillows were white. With the application of calligraphy, the white surfaces transform into beige. The model then becomes the only distinguishable figure since her skin and hair contrast with the rest. The calligraphy suggests the decomposition of the architectural space, furniture and clothing. The role of architecture, too, has always been defined by men in Islamic societies. Traditionally, the hierarchy of men is manifested by their presence in public spaces, coffee shops, shisha bars, working environments, the streets; women, traditionally have been confined within the four walls of a private space, usually a house. Through the use of calligraphy and its effect of deconstruction, Essaydi destroys these hierarchical patterns related to Islamic architecture and Western stereotypical notions. Floor and wall are only vaguely separated, while the presence of pillows becomes more ambiguous.

Calligraphy derives from the Greek word καλλιγραφία —”good” (καλή) “writing” (γραφή) — even the etymology of the word implies its use to construct not only legible sentences, but beautiful ones. As demonstrated in Essaydi’s work, calligraphy can have two natures: literal and visual. Her handwriting uses the two natures of calligraphy together to create shapes of personal expression. Les Femmes du Maroc #14 fuses together the three separate categories of drawing suggested by Daniel Mendelowitz in his early history of drawing: (1) Drawing as a record of what is seen: she uses photography to capture a certain moment in time, a constructed or conceptual scene derived from something real. (2) Drawing as a visualization of what is non-existent: through the suggestion of imagined meanings and relationships through the calligraphic lines. (3) Drawing as a graphic symbol: her work uses linguistic signs to suggest meaning.[13] Alphabetical characters can be understood for their literal meaning in Essaydi’s work, yet the literal and suggested meanings constantly challenge one another, to create a veil of protection and a drawn expression that escapes the strict rules of language – and culture.

[1] Annemarie Schimmel and Barbar Rivolta, “Islamic Calligraphy,” The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin 50, no. 1 (1992), 3.

[2] Schimmel and Rivolta, “Islamic Calligraphy,” 3.

[3] Schimmel, and Rivolta, “Islamic Calligraphy,” 17.

[4] Lalla A. Essaydi, “Disrupting the Odalisque,” World Literature Today 87, no. 2 (2013): 63.

[5] Anna Rocca and Lalla Essaydi, “In Search of Beauty in Space: Interview with Lalla Essaydi,” Dalhousie French Studies 103 (2014), 126.

[6] Cornelia H. Butler and Catherine de Zegher, On Line: Drawing Through the Twentieth Century (New York, NY: Museum of Modern Art, 2010), 23.

[7] Schimmel and Rivolta, “Islamic Calligraphy,” 17.

[8] Venetia Porter and Isabelle Caussé, Word into Art: Artists of the Modern Middle East (London, UK: British Museum Press, 2006), 15. Thanks to Emma Chubb for this reference.

[9] Anna Rocca and Lalla Essaydi, “In Search of Beauty in Space: Interview with Lalla Essaydi,” 119.

[10] John M. MacKenzie, Orientalism: History, Theory, and the Arts (Manchester, NY: Manchester University Press, 1995), xii.

[11] Rocca and Essaydi, “In Search of Beauty in Space: Interview with Lalla Essaydi,” 126.

[12] Essaydi, “Disrupting the Odalisque,” 65.

[13] Daniel Marcus Mendelowitz, Drawing (New York : Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1967), 8.