By Nicholas P. Fernacz

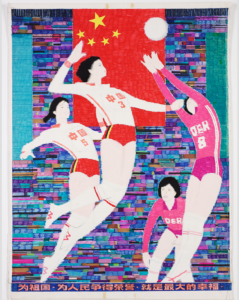

Xu Wenhua 徐文华, a Chinese artist and poster maker not well known in the United States, was born in Shanghai in 1941. This paper attempts to historicize one of Xu Wenhua’s works in the Smith College Museum of Art Collection, Volleyball (To Win for Your Motherland brings the Biggest Happiness), 1992 (SC 2004:40-7) (Fig. 1) in the context of both the history of Chinese propaganda posters, specifically sports propaganda, and the aesthetics of drawing as a medium. Although there is almost no scholarship on Xu Wenhua in English, his work relates to important contemporary developments in the history of Chinese propaganda posters. Volleyball epitomizes the propaganda produced in China in the 1980s and 1990s. Sport propaganda covertly propagated ideas the State wanted to reinforce during the Four Modernizations period (1977-2000), in contrast to the overt propaganda of the preceding Cultural Revolution phase (1966-1976). I argue that Xu Wenhua attempts to use the practice of drawing to highlight a playfulness that was not necessarily allowed in propaganda prior to the opening up of the country under Deng Xiaoping. While Xu Wenhua’s Volleyball is a work of covert propaganda that serves the State, he ultimately intends to produce artwork for the people, through the playfulness of his use of color and line drawing, and his rejection of the standard visual elements of Chinese propaganda. These factors illuminate his individual approach to producing artwork for the collective.

Fig. 1: Xu Wenhua, Volleyball (To Win for Your Motherland Brings the Biggest Happiness), 1992. Gouache, color pen with ink over graphite and collage on paper, 31 x 21 1/2 in. Smith College Museum of Art, SC 2004:40-7. Gift of Andrew Kim and Wan Kyun Rha Kim, class of 1960

Xu Wenhua studied at the Shanghai Opera School where he was instructed in the Oil Painting Section.1 While oil was the most important medium of Socialist Realist art during the Cultural Revolution, Xu Wenhua became interested in using the medium for landscape painting, not laden with the political ideologies of the State. After he began teaching at the Shanghai Light Industrial Art School, he painted works like Winter Scene with Houses and Snow, 1980-1990 (Fig. 2). This work, also in the Smith College collection, also relates to modern Chinese art history and the introduction of European academic painting traditions. In Winter Scene, Xu references the painting of the Impressionists, in an everyday landscape void of political leanings. The legacy of Impressionism and Post-Impressionism became a theme, through style, not content, in Xu Wenhua’s later work. Xu Wenhua taught at the Shanghai Light Industrial Art School until he moved to the United States in 1986 for personal study.2 Like many other Chinese intellectuals, he may have feared another period like the Cultural Revolution.

Winter Scene with Houses and Snow suggests that Xu Wenhua intended not to produce propaganda, but rather to become a classically trained artist. Smith College Museum of Art owns six works by Xu: five propaganda posters and one oil painting, Winter Scene.3

Fig. 2: Xu Wenhua, Winter Scene with Houses and Snow, 1980-1990, oil painting, 7 1/8 x 10 1/4 in. Smith College Museum of Art, SC 2013:37. Gift of Claudia Hill in honor of her parents Grace Hope Hill and Professor Errol Gaston Hill

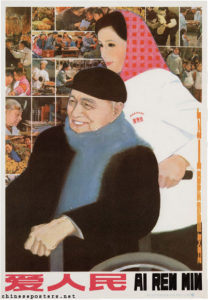

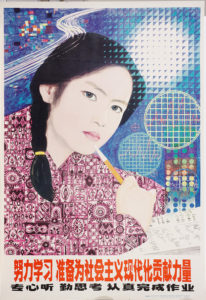

Winter Scene illustrates Xu Wenhua’s admiration for the European academic painting tradition that inspired Socialist Realism. In this landscape he works to depict a politically neutral landscape, perhaps one painted from life. In the propaganda posters he produced, other elements suggest his awareness of European modernism. For instance in Love The People, 1983 (Fig. 3), Xu Wenhua references the photomontage tradition. In other works, like Healthy Eating, 1981 (Fig. 4) and Study Hard, Prepare for the Progress of the Socialist State, 1980 (Fig. 5), he experiments with texture and pattern, producing intricate tessellations in the shirt pattern. For propaganda images, these elements would be completely unnecessary. These details, which define the specific aesthetic of the posters, suggest that Xu Wenhua is more interested in producing artwork than propaganda.

Fig. 3: Xu Wenhua, Love the People, 1983, poster, 30 3/10 x 20 4/5 in. Landsberger Collection, BG E13/261

Volleyball proposes that strong national identity and unity will allow the Chinese to overcome any political rival, a message the State hoped to propagate. However, this work also further demonstrates his post-Impressionist influence, and pursuit of an artistic career. Volleyball is a small-scale drawing formatted like a poster with a propagandistic message at the bottom. It features two Chinese athletes, indicated by the “中国” displayed on their uniforms, defeating a nationally ambiguous team. The opposing team’s color scheme of pink adds a layer of ambiguity, since pink is a very rare color among national flags; perhaps the only flag featuring pink is the flag of Espírito Santo, a state in Brazil. The smooth curves and athletic bodies of the two female Chinese athletes indicate strength through a youthful healthy appearance. Both Chinese athletes lunge through the air making a successful spike, as indicated by the ball’s progress beyond the defender’s block. The pose reiterates Xu Wenhua’s message of strength through cooperation. A spike of the volleyball onto the other side of the court indicates the strength the nationalistic Chinese team possesses, implicitly possible because of the cohesion of the women working together, the unity of the team a paradigm of national unity.

Fig. 4: Xu Wenhua, Healthy Eating, 1981, drawing, 31 x 21 5/8 in. Smith College Museum of Art, SC 2004:40-5. Gift of Andrew Kim and Wan Kyun Rha Kim, class of 1960

The minimalist graphic quality of the two Chinese athletes, particularly their homogenous faces, makes it unclear whether the two women are individuals or simply representatives of a collective. This quality of the drawing reinforces Xu Wenhua’s message about strength through national identity. The opposing team appears particularly weak, with one athlete blocking the ball in defense, and the other athlete bending down awkwardly to catch her breath. All four of the women in this drawing are virtually indistinguishable as individuals, their faces nearly identical, however their uniforms distinguish the four into teams of two. The two team members on either side are in fact only distinguishable by the assigned team number featured on their shirts (3 and 5 on the Chinese side). The Chinese athletes are in a graceful harmony, almost dance-like in their composition, while the opposing team appears incoherent and awkward. The volleyball net has been removed from this scene, making it more symbolic, and possibly suggesting that the Chinese athletes have transcended the game in achieving their monumental victory. The space surrounding the athletes becomes flattened and purely symbolic as a result.

Xu Wenhua further references the post-Impressionists in his work through the color and background in Volleyball. In particularly, the small and controlled linear pen strokes are reminiscent of Georges Seurat’s pointillist technique, replacing Seurat’s points of color with careful lines in equally controlled patterns. This color application is striking and unique. It appears Xu Wenhua used markers to create little lines and boxes, creating planes of turquoise blue, purple, and pink color which trick the eye into seeing the background as a crowd of people. This technique also adds to the dynamic quality of the image, which creates an impression of blurred movement. Turquoise, purple, and pink are colors completely disassociated from Chinese propaganda, but trendy in popular culture in the 1980s, suggesting a further from break from the methods of propaganda. The pointillist references in this drawing covertly turn Xu Wenhua’s image from propaganda into artwork, despite the propagandistic message at the bottom that gives the work its title.

Fig. 5: Xu Wenhua, Study Hard, Prepare for the Progress of the Socialist State, 1980, poster, 31 1/2 x 21 in. Smith College Museum of Art, SC 2004:40-3. Gift of Andrew Kim and Wan Kyun Rha Kim, class of 1960

Behind the athletes, staging the focal point of the drawing, appears the lower part of the flag of the People’s Republic of China. The flag serves as the backdrop for the climactic action of this drawing. The red color of the flag, the only propagandistic visual aspect of the work, stands out from the blue and purple of the background, drawing the viewer’s eye to both the strength of the spike, and the strength of China. The central figure with her arm above her head ready to spike the ball appears, at the same time, to salute the flag. The floating stars replace the “POW” that might appear in a comic strip image of the same scene; in fact, the simple style of the figure drawing recalls such comic images. On either side of the Chinese flag are two other unspecified flags or banners in turquoise and teal, nonstandard flag colors again although they may also represent the host country of the games being depicted, or the flags of the countries that will take second and third place in the championship.

Until the 1911 Revolution, after which athleticism was absolutely necessary for a country aspiring for national strength, sports in Imperial China were largely held with low esteem.4 After the 1911 Revolution, China entered the Republican Period (1912-1949). During these years, in sport, the Chinese government placed greater emphasis on physical education and sports, and began to send teams to compete internationally. Notably, the first international competition in which China competed was in 1913 at the Far Eastern Championship.

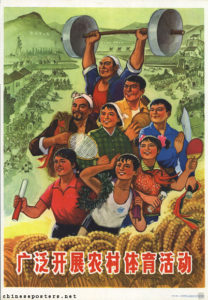

Art from the 1950s through the 1970s captures the emphasis placed on good personal health the Chinese government advocated under Mao Zedong. Sports became widely popular once Mao wrote about the benefits of physical health in “A Study of Physical Culture,” where he advocated “regular exercise and swimming.”5 Mao Zedong was an avid swimmer himself, and was in fact painted swimming at various times by a number of artists. Dr. Stefan Landsberger’s personal collection of posters includes multiple depictions of healthy Chinese people going to train and engage in sport. Two such works are On the way to the new sports field, 1954 (Fig. 6), and Develop physical education activities in peasant villages, 1975 (Fig. 7).

Fig. 6: Zhang Qianyi, On the Way to the New Sports Field, 1954, poster, 20 4/5 x 30 3/10 in. Landsberger Collection, BG E13/717

These works depict peasants in the pursuit of physical fitness. While they differ from Volleyball in their emphasis on naturalism and the depiction of a three-dimensional space, they are ancestors of the poster as earlier propaganda relating to sports culture in China. These peasant works place emphasis on the common people; Volleyball, like other propaganda posters depicting sports teams in China, shifts away from this emphasis, focusing instead on the star athletes of major competitions, even if they are shown as anonymous athletes. Further research might illuminate this shift in Chinese culture, from the collective to the individual, particularly in sports propaganda.

Although China failed to be successful at its first international competition, the 1913 Far Eastern Championship, it rallied the country behind a national team, whereas previously people would place support behind their local teams. Dr. Landsberger writes that “taking part in sports, was not merely seen as promoting the people’s health, national defense and production, but also as inspiring the collective work spirit necessary for the national unity which was considered a prerequisite to national construction.” To achieve national unity required an emphasis on massification, meaning integration with common people. This word can be understood to mean homogenization. Political study and ideological training were involved in the preparation of high level athletes at the Communist headquarters in Yan’an, and other parts of China. To bring glory to China, the model athlete of the 1960s possessed these qualities, described by Landsberger: “unwavering in ideology, kept up his or her physical fitness under all conditions, mastered the game, did not spare him- or herself in training, and went all out in competition.”6 Finally, after the Cultural Revolution when the Four Modernizations were being established by Deng Xiaoping, sports became an important aspect to achieving the political ideals of China. It was important for Chinese citizens to train their bodies and minds, in order to achieve the economic goals of the State. 1980s propaganda posters promoted images of the common Chinese citizen training once again. This gives further context to Xu Wenhua’s Healthy Eating (Fig. 4). Healthy Eating’s messages in Mandarin Chinese urge the viewer to prepare meals hot, so that they bring good nourishment, and then clean one’s dishes well to prevent disease.

Fig. 7: Zhao Kunahn, Develop Physical Education Activities in Peasant Villages, 1975, poster, 41 9/10 x 29 1/10 in. IISH Collection, BG E3/751

In 1981 the Chinese women’s volleyball team defeated Japan at the World Championships. This victory marked the beginning of a long history of highly successful Chinese women’s volleyball teams, and reestablished national pride in the Chinese public, a pride relatively dormant since the beginning of the Cultural Revolution. Xu produced his Volleyball image in 1992, a year after the Chinese women’s volleyball team won the Asian Women’s Volleyball Championship over Japan. This victory was China’s third title at this Championship. This history is important to understanding Xu Wenhua’s Volleyball, in order to establish why the sport would be depicted in this way in Chinese propaganda posters. These victories over Japan presumably inspired great interest in volleyball, particularly given China and Japan’s tumultuous history.

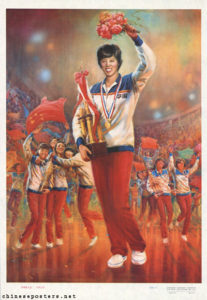

Because of the success China achieved internationally, depictions of team sports became much more popular from the mid-1980s to the early 1990s, particularly of the national sports teams that did well in international competition. In 1990 a poster titled Chinese Women Volleyball Team (Fig. 8) was produced. This work provides a visual counterpoint to Xu Wenhua’s drawing. In this poster female athletes from the women’s volleyball team are celebrating a world championship victory, trophies in hand and the flag of the People’s Republic of China draped across their backs.7 This poster, similarly to Xu Wenhua’s drawing Volleyball, depicts national strength through unity, physical fitness, and youth.

However, Xu Wenhua’s work diverges from Chinese Women Volleyball Team by neglecting the celebratory nature of propaganda posters depicting victorious teams. The strong differences in color, space, line, and composition between these two works highlight the uniqueness of Volleyball. While their propagandistic messages are similar, Xu Wenhua works from a different visual language, one that he developed through the study of European artists. He may have been influenced by popular culture as well, such as cartoon drawings or Japanese manga, which would account for the flatness of the figures and the space in his image. Xu Wenhua is less interested in depicting a recognizable volleyball match than in developing new techniques of mark-making and patterning. His work reflects a more experimental artistic practice, over the production of propaganda promoting the State’s wishes in a conventional style.

Fig. 8: He Duojun, Chinese Women Volleyball Team, 1990, poster, 30 3/10 x 20 4/5 in. Landsberger Collection, BG E13/471

During the Four Modernizations period after the death of Mao Zedong and the end of the Cultural Revolution, Deng Xiaoping set forth goals to improve China’s agriculture, industry, national defense and science fields. Athletic and sport propaganda was a subversive form of media that allowed the State to push a covert narrative. In comparison, posters from the Cultural Revolution are very clear about promoting a call-to-action for students to become revolutionaries in Chinese society. This later propaganda, relating to current events, sport culture, and images of contemporary political leaders, was more subtly coercive in removing the overt politics of previous Chinese propaganda. The State, through sport propaganda, promoted the attributes it wanted the masses to possess by emphasizing images of athletes, who embodied national spirit in the guise of personal fulfillment. The State believed that “training the body and mind” would allow for the realization of the economic goals of the Four Modernizations. This permeated the propaganda of the time, and appears in Xu Wenhua’s posters, as well as propaganda by other artists. The State could achieve the model citizens it desired through covertly propagating physical fitness and proper health. Through healthiness, the State would improve its agriculture, industry, and national defense, as well as the science and technology fields. With a more able population, these goals would be fulfilled more easily. Through sport propaganda physical fitness would become expected in Chinese society, therefore realizing the Four Modernizations without reverting to the more heavy handed revolutionary ideology of the Cultural Revolution.

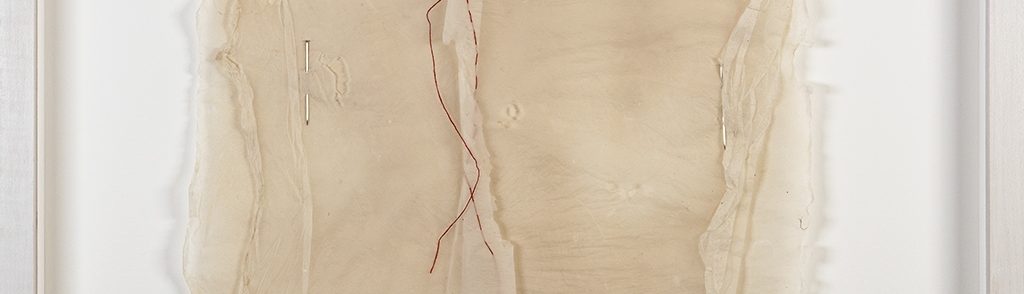

While Xu Wenhua’s work does depict what the State wanted from its people, it diverges from the common visual language of propaganda that other artists produced. This relates directly to Volleyball’s status as a drawing rather than a more “finished” work of art. Because Volleyball is a drawing, Xu Wenhua could develop more experimental methods of mark-making and composition. The unique method of applying the medium that Xu Wenhua uses is rooted in the post-Impressionist techniques of artists like Seurat; evidently Xu Wenhua was highly inspired by the education he received in European methods of painting, both academic and avant-garde. Volleyball, in addition to its relevance to Chinese histories of sports propaganda, also relates to the history of drawing as a means of artistic exploration and experimentation. Drawing was often done as a preparatory medium. While some drawings can take on the role of a “finished work,” it is unclear whether Volleyball would be considered finished by Xu Wenhua. There could be arguments either way, given that the paper is covered evenly with color, but the work never became a reproducible poster.

Volleyball relates back to the sports histories discussed above: the 1913 turn in Chinese sport culture, the shift of national attention to a sole Chinese team, rather than a local team, and the Chinese women’s national volleyball team becoming very successful on the international stage. It applies to the use of sports propaganda to further the State’s Four Modernizations goals. This historical contextualization creates a deeper understanding of the imagery of Volleyball, but does not explain why Xu Wenhua expends the energy experimenting with texture and pattern in this and other posters. These visual properties examined through the art-historical tools of formal analysis identify what makes these works unique artistic statements.

When first analyzed, Volleyball, appears simply as a piece of propaganda for the State. However, upon further investigation through formal analysis, in relation to Xu Wenhua’s larger oeuvre, it is apparent that Xu to some degree rejected his role as a propaganda producer. His works express his individuality as an artist and designer, as much as he could through his posters. This is evident through the references to European artists and the experimental techniques and patterns that appear throughout his work. Volleyball (To Win for Your Motherland brings the Biggest Happiness) allows for multiple interpretations, and provides clues for a deeper understanding of its author. Despite Xu Wenhua’s role as a covert propaganda producer for the State creating messages promoting good health and national unity, his passion for artistic creation is also evident in his work. Xu Wenhua (Fig. 9) actively creates propaganda that is visually distinct from the Chinese propaganda created by his contemporaries, ultimately suggesting his artistry, and the use of color and composition as personal expression.

- Stefan Landsberger, “Xu Wenhua (徐文华),” Chineseposters.net ↩

- Landsberger, “Xu Wenhua (徐文华)” ↩

- Gaskin, Kayla A. “Xu Wenhua 徐文华.” Smith.edu ↩

- Stefan Landsberger, “Sports,” Chineseposters.net, 16 Dec. 2016 ↩

- Landsberger, “Sports.” ↩

- Landsberger, “Sports.” ↩

- Stefan Landsberger, “Chinese women volleyball team,” Chineseposters.net, 16 Dec. 2016 ↩