by Jessica Chien

In a time of rapid climate change and an administration that does not put the earth first, emphasis on the importance and beauty of the natural land and the resources that come with it becomes very important as a way to raise awareness for the fragile Earth that we all share. Land Art (or Earth Art) is a type of art that makes use of natural material and environments. With the use of natural materials such as branches, leaves, soil etc, this art rejects the heavily wasteful materials primarily used in the art world. This form of art may be created directly in nature using materials that are found in the environment such as rocks, branches, or different objects specific to the landscape. Land Art has a unique temporality as well, since the environment is always changing through erosion or weather, and results in a finished piece that often itself changes over time.

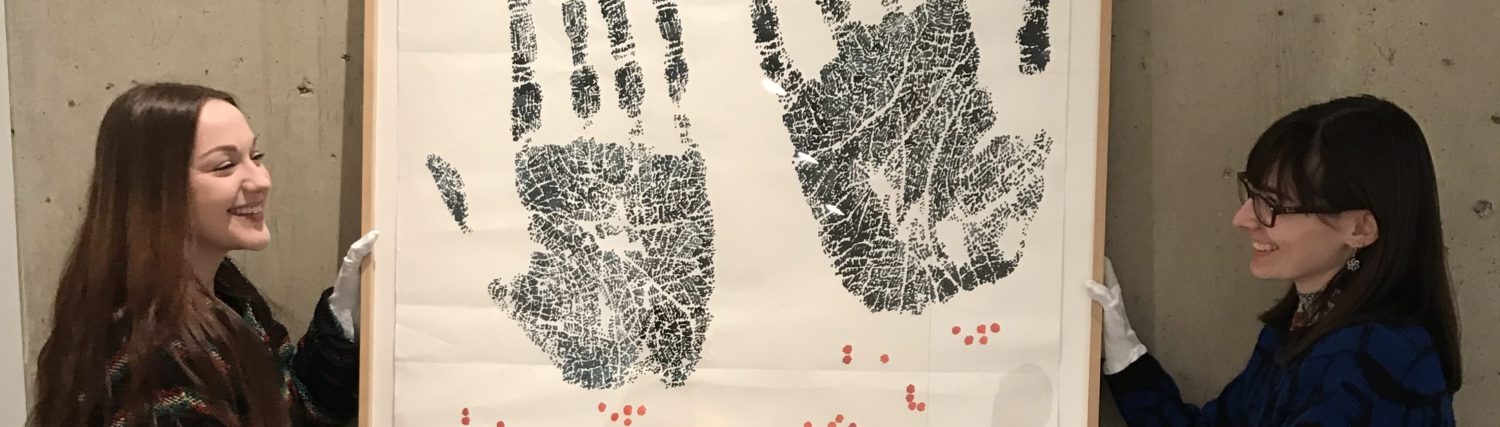

Artist and sculptor David Nash, pictured with his Ash Dome near his home in Blaenau Ffestiniog, north Wales. Ash Dome, planted as saplings in 1977, is now a mature dome centered on a plot of woodland owned by the artist, a sort of outdoor studio. Photograph by C. McPherson, 2011.

During the construction of Land Art, artists often work outside of their studios, moving their practice to natural environments rather than remaining confined to four walls. Working in an environment very different from their regular studio practices, some had a very conscious approach about how they related to that environment. American artist Alan Sonfist (b. 1946) takes great care not to change or impact the environment in any way while he creates art. He takes from the ground and returns the materials back to nature, if possible, when he is done creating his piece. Other artists have a different approach. In a noninvasive way, David Nash (b. 1945), a British sculptor of the same artistic generation as Sonfist, either takes objects from the natural environment and places them into a human-made space or distorts and manipulates the natural environment in order to show the presence of human manipulation, in the tradition of landscape gardening. These different practices build different narratives for each work that is made with the use of natural materials. Comparing and contrasting art works by Sonfist and Nash illuminates some of the central practices and problems at work in Land Art, relating to the way artists use drawing to develop their projects and rethink their relationship to artistic materials and ecology.

As Eleanor Heartney reports, “Early in his career, Sonfist made a pledge to himself that he would never destroy a natural environment in order to create his artwork.”[1] Sonfist made this pledge because other land artists at the time–most notably, Robert Smithson and Michael Heizer–were exploiting land and resources by bulldozing the earth and removing soil from the ground. The most well known work of Sonfist’s is his Time Landscape (1965), a garden on the corner of LaGuardia and West Houston Street in New York City. This piece is an attempt to recover the native land that was once present at the site thousands of years ago. Time Landscape (1965) is described as, “the recreation of a section of the locale’s original natural state or states within the city itself.”[2]

The project used native New York botany and geology to create a 25’ x 40’ forested area, preserved from development by the stewardship of the New York City Parks and Recreation department. The Time Landscape was in part a response to Sonfist’s sentimental connection to the hemlock forest where he grew up in the Bronx. Driven by his memory of the deterioration of the forest, loss and the passing of time have become two large components of his work. Much of his work references memory and the attempt to recover something that was originally untouched by human hands.

Sonfist believes that, “as humans we are part of the environment.” He does not like to associate himself with the more well-known Land Artists due to the exploitation of the land that happens during much of their art making. Sonfist carefully works to show the viewer the fragility of the land and the continuous struggle necessary to protect it. Much of his work is about the preservation of the environment as well as leaving no human trace on a portion of land. The preservation aspect is evident in the re-planting of the land in Time Landscape. The concept of eradicating the human trace is foregrounded in his “Earth Mappings” and “Surface Memory” series.

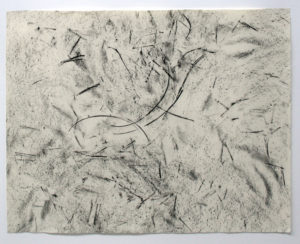

Alan Sonfist, American (b. 1946), Earth Mapping of New York City, 1965. Charcoal on paper, 19 in x 22 in. University Museum of Contemporary Art, University of Massachusetts, Amherst. Purchased with funds from Alumni Association, UM 1986.67.

In the “Earth Mappings” series, Sonfist honors the natural soil and uses its texture to make marks directly on the paper. In works like the UMCA’s Earth Mapping of New York City (1965), Sonfist hopes to capture what is absent in the current landscape. His process involves going through historical photographs that suggest what the undisturbed natural environment would look like in a particular area. Sonfist says in his artist statement: “To understand a place one must be aware of the history which lies underneath it, as the scars and markings on our bodies remind us of our past, the earth continually reminds us of its own through human and natural intervention.”[3]

In Earth Mapping of New York City it is not immediately clear how the abstract drawing relates to a landscape. Delicate clusters of black dots are present throughout the paper and gestural curved marks appear at various places in the center. It is hard to make a connection to the large city of New York. The drawing has no foreground or background, suggesting that the splay of marks may be from an aerial view of the ground. Each line and mark looks quick, without predetermination or control from the artist. These earth mappings developed out of the earlier series “Surface Memory.” This series featured drawings made by rubbing charcoal and paper on forest floors. Sonfist would either take the natural forest floor in the composition as he found it and rub from that or he would manipulate found pieces to create a composition. He created Earth Mapping of New York City through a similar process, notably recording a trace not of the typical urban environment, but rather of one of the city’s green spaces.

Through this process Sonfist attempts to directly materialize the idea of the past and the forgotten surface of natural untouched earth. The act of rubbing is important rather than simply drawing or painting the landscape, because after the paper is lifted away from the subject, the drawing on the paper becomes what is left of the surface: a “surface memory.” The rubbing process fully records the contours of the natural topography. Without a physical object underneath the paper, it would be impossible to obtain a mark. Sonfist relies on the physical properties of nature to create their own mark on the paper. I believe in this process of art and mark making, Sonfist acts as a tool or a middleman to speak for nature. Even if Sonfist rearranges part of the forest floor for a composition, the whole drawing becomes dependent on the random found materials. The process of rubbing ephemeral organic materials gives the work an ephemeral aspect related to the fragility of nature and how humans can easy change nature in ways that we may not intend to.

Since the drawing registers a trace of the earth that was used to make it, it raises the question of what the earth’s surface once looked like. With Sonfist’s Earth Mapping of New York City, the viewer is challenged to visualize a landscape that predates humans. What is the natural earth underneath all of the infrastructure, the streets, and the roads? Has urban development gone so far that we can’t visualize a world without civil engineering? Sonfist chose one of the most busiest cities in the world for his inspiration. His childhood connection to New York is significant in this because for Sonfist, the forest beside his house served as a safe haven amidst the chaos of the city. If the earth were less settled, would people still need to seek out these natural “safe havens”?

David Nash also uses nature as the main source and medium of his art. By changing the way the environment looks and using nature to build earth sculptures, Nash creates scenes that are made of nature but cannot be found in nature without human help. Nash uses found natural material in his work. He began by using primarily wood in his sculptures. He would take tree limbs that were either dead or dying and make them into sculptures of table forms. Most of Nash’s work involves applying brute force using tools such as chainsaw, axe, chisel, and hand saw. The use of these tools would have been anathema for Sonfist. Nature and machinery are two very opposite components in his view. Nash, on the other hand, was greatly influenced by the industrial work of American minimalism and was drawn to how the movement was “honest in its use of form and material.”[4]

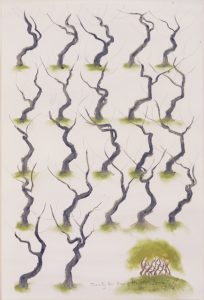

David Nash, British (b. 1945), Leaning Out of Square, 1978, charcoal, graphite and earth on paper. Mead Art Museum, Amherst College. Gift of Andrew G. Galef (Class of 1954) and Bronya Galef, AC 2004.108.

Yet, Nash’s work moves into a post-minimalist approach in using natural form and growth to comment on or break out of the inorganic grids that defined minimalist composition.

Nash’s Leaning Out of a Square and Ash Dome drawings are related to the Ash Dome sculpture he began in 1977 in Wales. Each drawing helps envision the concept behind a time-based piece. The drawings are minimal in design and serve a practical function in showing the viewer what the sculptural work will look like. In Leaning Out of Square, Nash provides us with a perspective bird’s eye view of the grid of birch seedlings. The seedlings are placed in a four by four grid, each spaced identically apart. The drawing shows that each seedling will be shaped by the artist to grow in a separate direction.

David Nash (British, b. 1945), Twenty-two Trees of the Ash Dome, 1995. Pastel and graphite on paper. Mead Art Museum, Amherst College. Gift of Andrew G. Galef (Class of 1954) and Bronya Galef, AC 2004.105.

In the Ash Dome drawing, Nash uses vine charcoal to draw multiple spindly trees grown in a circle, climbing upward to eventually meet each other. Nash includes some shadowing at the bottom of each trunk to provide a sense of gravity for the viewer in Ash Dome, but neither drawing includes a foreground or a background. The drawings only show what is important about the piece to the viewer and disregard any extraneous backgrounds that may take away from the form developed through natural materials.

Unlike with Alan Sonfist, human intervention is very prominent in the work of David Nash. For Ash Dome, he planted 22 trees in a circle and then manipulated them to create a dome-like shape. The trees were “rigorously wedged, bent, and pruned to curve inward, an effort that they have stubbornly resisted.”[5]

This manipulation of nature and trees would have never been seen in any of Sonfists’s works. If a someone takes a walk into a forest and sees Ash Dome, they will know that a human created it. The message is similar to stacking rocks. The form is so unnatural in its environment that you know without any other information that the presentation of those objects is anything but natural. As Nash explains, “A dome form seemed most appropriate as it was clearly a human intervention and it reflected forms already in the immediate landscape.”[6] Someone must have had to come and manually bend and warp the trees throughout the years in order for them to grow at such peculiar angles.

Both Sonfist’s Time Landscape and Nash’s Ash Dome are still growing. The Ash Dome will definitely outlive Nash and anyone who might be in charge of taking care of the trees. In both works, nature is still dominant because of the lifespan of a tree. When Nash works with these growing sculptures, he must take into account the time it will take for a sapling to grow into a mature tree; the sculpture is never actually “finished” in a traditional sense. In this way, the drawings can fulfill the usual function of art to provide a finite object that in this case also documents the work: the never-finished sculpture.

As Sonfist and Nash create their own works in their own ways, using very different methods but very similar natural materials. Each method changes the message that the artist wants to get across. For Sonfist, the art becomes more of a tribute to something that is gone. The viewer is made to contemplate their relationship with nature and the footprints that they leave behind. Nash, on the other hand, uses nature as his tool. The act of planting seedlings in the ground is obviously an act of environmental stewardship and conservation, however that isn’t the only meaning of his works. Nash approaches nature more as a challenge. The compositions that Nash creates in the outdoors tame the wilderness and give order to the random nature of the forest. These different methods of using nature as material create different narratives for each work, each ecological in its own way.

The use of natural material in Land Art has remains a fairly new medium for artists in the United States and the United Kingdom. All these works pay tribute to nature because it is nature that provides the materials and inspiration for the works made by the artists.

[1] Alan Sonfist, Eleanor Heartney, and Stephen S. Prokopoff, Alan Sonfist: History and the Landscape (Iowa City: University of Iowa Museum of Art, 1997).

[2] Sonfist, Heartney, and Prokopoff, Alan Sonfist: History and the Landscape.

[3] http://www.alansonfist.com/

[4] Nicholas Alfrey, Joy Sleeman, and Ben Tuffnell, Uncommon Ground: Land Art in Britain (London: Hayward Gallery in Association with Southbank Centre, 2013).

[5] Twylene Moyer and Glenn Harper, The New Earthwork: Art, Action, Agency (Hamilton: Isc, 2011).

[6] David Nash and Norbert Lynton, David Nash (New York: Abrams, 2008).