(Fig. 1) Peter Paul Rubens, Shepherds and Shepherdesses in a Rainbow Landscape, oil on canvas, c. 1630

Of the twenty-four etchings published by Herman de Neyt (1588-1642), only eleven of the original drawn designs have been located. All of the drawings have been attributed to the Venetian draughtsman, Domenico Campagnola (1500-1564), who worked a century prior to the production of the set.[1] The landscape drawings are generally consistent in size, drawn in pen and ink entirely in a linear mode with long, thin, and crisp lines stretching through the pastures and skies. Smaller parallel cross-hatching marks model other forms, such as the figures, architectural structures, and foliage. Though these drawings were perhaps not intended to be transformed into prints, Campagnola’s use of a linear mode of representation recalls the techniques used by printmakers, especially for delicate lines in etching. The linear mode, made up of thin lines and crosshatching appears in both the drawings and etchings. Because of this stylistic quality, Campagnola’s drawings were ideally suited for adaptation into the etchings that de Neyt published a century later.

All eleven of the Campagnola drawings reproduced in the de Neyt set are about ten by fifteen inches, which suggests that they each came from the same collection of drawings or were perhaps part of a sketchbook.[2] The dimensions of the engravings from the de Neyt set are very similar to those of the individual Campagnola drawings, indicating they were directly copied from the originals. Though the drawings are Italian, it is likely that they made their way into Herman de Neyt’s personal collection in Antwerp. De Neyt’s inventories mention an extensive collection of Italian works that could have also included the Campagnola landscape drawings.[3]

Landscape drawings would have been especially useful for the backgrounds of painted compositions, providing the artists with detailed imagery and variation for their designs.[4] Campagnola’s compositions, if originally compiled into a sketchbook, might have provided a portfolio of readily accessible landscapes for artists to borrow in their own compositions. For example, Robert Cafritz has observed that is likely that Peter Paul Rubens (1577-1640) had access to at least one of the Campagnola drawings that was used later in the de Neyt set.[5] In Shepherds and Shepherdesses in a Rainbow Landscape of 1630 (Fig. 1), the sloping and thatched roof architectural structures in the background have been borrowed from a Campagnola design that corresponds, in reverse, to the sixth print in the de Neyt set (Fig. 2). Though the original drawing has not been located, the orientation of the architectural detail, which would have been reversed in the printing process, suggests that Rubens’ source was Campagnola’s drawing rather than the de Neyt etching.[6]

(Fig. 4) Detail from, Domenico Campagnola, Landscape with Figures and Animals, Pen and brown ink, within pen and black ink framing lines 9 ½ x 14 5/8 in. The Collection of A. Alfred Taubman: Old Masters, Sotheby’s, 1500-1564.

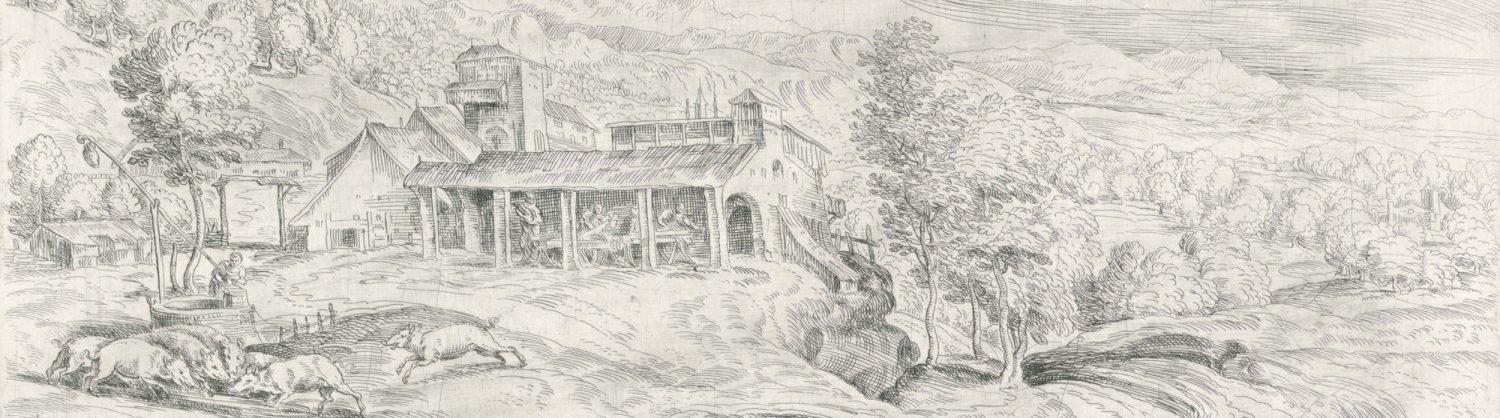

Looking closely at the Campagnola drawings reveals the artist’s technical process while also demonstrating their reuse in the de Neyt set. For example, the drawing located in the Smith College Museum of Art, Landscape with Farmyard, corresponds to the fifth etching in the de Neyt set, and has been dated to the 1550s (Fig. 3).[7] The artist used pen and brown ink over traces of black chalk to compose this farm scene with cattle, geese, and roosters roaming the pastures.[8] Beginning with the easily erasable black chalk, Campagnola allowed room for error and erasure before finalizing the finished drawing. Unlike a rapid ink sketch, showing the artist’s inspiration unfolding in quick paced gestural lines, the Campagnola drawing begins with dry chalk as a preliminary means to plan the finished ink version, similar to a painter beginning with an underdrawing.

(Fig. 5) Giluio Campagnola, St. John the Baptist Standing Against a Landscape, engraving, 34.2 x 23.7 cm, c. 1505, ©Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Kupferstichkabinett / Volker H. Schneider.

(Fig. 6) Detail on right from St. John the Baptist Standing Against a Landscape.

Such preliminary chalk drawings were described by Cennino Cennini, who made the distinction between the imaginative rapid sketch and the planned underdrawing. He advised artists to produce a light chalk sketch before applying the final permanent medium, such as the ink over Campagnola’s chalk drawing. Cennini explained that if you err with chalk, “take a feather, and rub with the barbs of this feather—chicken or goose, as may be—and sweep the charcoal off what you have drawn.”[9] Cennini then stated, “when you feel that [the drawing] is about right, take the silver style and go over the outlines and accents of your drawings, and over the dominant folds, to pick them out.”[10] In Campagnola’s drawings, the artist has gone over his composition with ink rather than silverpoint to make it permanent.

One of Campagnola’s foremost skills in drawing is his variety of line, ranging from thick in the foreground to thin in the background. In Landscape with a Farmyard, this variety of marks is explored in the thick application of line that contours the tree trunks and cow’s backs in the foreground, but then dissolve into thinner, more delicate lines for the distant landscape. The variation of line width helps to create an atmospheric effect. This is observed for example in a detail from Landscape with Figures and Animals (Fig. 4) The use of crisp thick lines to contour the cows’ flanks in the foreground and the tree trunks just beyond enhances the illusion of depth. Moving further into the background, distant mountains are composed of thinner strokes to contour their jagged shape. In addition, the sweeping vertical lines modeling the shadows on the mountains look as if Campagnola applied pressure with the inked pen from the bottom, then lifted slightly as he drew up, leaving behind a thinner line as the pen lifted. The pen marks become thinner as they reach the mountain tops, once again to create atmospheric distance.

Close inspection of this drawing in the areas where the drawn lines are thinnest in the background, such as in the distant mountains, reveals faint impression marks created by a stylus pressing into the paper during the tracing process. These faint impressions pressed onto the surface on the drawing might indicate the way in which the printmaker transferred the original design for the accompanying fifth etching in the de Neyt set.[11] These impressed lines are important to consider because it shows that the printmaker could easily transfer the drawing directly into the plate for the etching.

(Fig. 9) Domenico Campagnola, Nymph in a Landscape, pen and ink with small retouches in gray, 12 x 17.5 cm, ca. 1516-17.

To understand Domenico Campagnola’s style it is necessary to consider his mentor and influences. In 1507, Domenico Campagnola was apprenticed and adopted by the painter and engraver, Giulio Campagnola (c. 1482-1518), from whom he acquired both his last name and his artistic training.[12] Giulio was a highly skilled and admired engraver who invented the stippling engraving technique, used particularly in figural work, such as in his St. John the Baptist Standing Against a Landscape (Fig. 5). A detail from this work of two seated figures among sheep demonstrates the artist’s application of small dots to create subtle modeling (Fig. 6). Giulio was attempting to emulate the gradual and soft modeling achievement he admired in Giorgione’s (1477-1510) paintings. Domenico’s engraved figural works adopt Giulio’s stippling technique, however his landscape and architectural elements remain in the linear mode. Two other works share a similar application of stippling to the figural body: Giulio’s Nymph in a Landscape of about 1509-10 (Fig. 7) and Domenico’s Nymph in a Landscape of 1517 (Fig. 8). Giulio’s nymph is composed entirely of stippling, while Domenico’s nymph applies the stippling technique only in the chest. Domenico departs from his mentor in the landscape. While Giulio continues to stipple his vegetation and architecture, Domenico primarily applies crosshatched lines.

(Fig. 10) Domenico Campagnola, Landscape with Shepherds Driving Away a Wolf, Pen and brown ink with touches of pale green wash on laid paper, 22.5 x 36.7 cm, Rosenwalk Collection, National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C., c. 1540.

A drawing at the British Museum is closely related to Domenico’s Nymph in a Landscape engraving and is generally accepted as the preparatory study for the work (Fig. 9).[13] There are considerable differences between Campagnola’s drawing and engraving, particularly in the organization of space. The composition of the drawing has been dramatically compressed for the engraving. The body of the engraved nymph reaches the edges of the sheet, whereas the drawn nymph has more space around her body. In addition, the atmospheric quality of the drawing has been lost in the engraved version. Domenico’s drawing is composed of thin applications of line, more densely cross hatched in the foreground, with lighter application of line in the background to show distance. The engraving however, is densely cross hatched throughout the entire composition. The soft curves of the nymph’s drawn image have been executed in a more angular and rigid style for the engraving. An important difference to note between Campagnola’s transference of drawings to print in the Nymph and the de Neyt set is the technical method and its restrictions. Because the de Neyt set was etched, rather than engraved, there would have been a smooth transition from the original Campagnola drawings to printed design. Etching allows for a more fluid application of line where you can press into the plate similar to drawing. In using etching, the craftsman could more accurately replicate Campagnola’s landscape designs, without compromising the drawn quality that seems to be lost when drawings are transferred through engraving.

(Fig. 11) Giulio Campagnola, Landscape with Two Men Sitting near a Coppice, pen and brown ink, pricked for transfer, 13.4 cm x 25.9 cm, after 1510.

By 1520, Domenico moved to Padua from Venice and became a leading painter, producing works for churches and palaces in the city.[14] Later, following in Giulio’s artistic tradition, he rose to fame for his drawings and prints. Landscape designs were the most abundant among his subjects. He produced designs as finished drawings, often sold to collectors.[15] His landscape drawings feature panoramic vistas with long, flowing, rhythmic strokes. In works such as Landscape with Shepherds Driving Away a Wolf, Domenico raises the perspective of the landscape to allow the viewer to peer into the scene from slightly above, extending the view into rolling pastures, winding paths, castles, and bridges that eventually lead to jagged mountains in the distance (Fig. 10).

Works by Titian, Giorgione, Giulio Campagnola, and Domenico Campagnola helped usher in a new specialty of Venetian art, in which the landscape takes on the dominant focus. The introduction of the composition focused on landscape can be observed in a drawing attributed to Giulio, Landscape with Two Men Sitting near a Coppice from after 1510 (Fig.11).[16] Two figures seated in the right foreground take up less than a third of the page; however the landscape stretches across two thirds of the sheet. The figures are not the focus of the composition, but are rather part of a larger landscape over which the viewer’s eye may wander. The composition has been pricked for transfer and was later used for an engraving, Shepherds in a Landscape of c. 1517 (Fig. 12).[17] Though Giulio began work on this engraving, he died in 1515, so it was then completed by Domenico who replaced the two seated men for musicians in the foreground. Domenico’s early engagement with this composition introduced the young artist to the growing importance of the landscape that he would continue to pursue in his own drawn compositions.

(Fig. 13) Titian, Landscape with St. Theodore Overcoming the Dragon, pen and brown ink, 29.6 x 29.7 cm, c. 1550s.

Domenico achieved a style during his artistic career that strikes a balance between both Giulio, his mentor, and Titian, who he admired. Whereas Giulio’s drawn landscape designs are short and angular, Titian’s are smooth and flowing. Domenico’s use of line finds a balance between his predecessors’ styles. This distinction is exemplified by Giulio’s Landscape with Two Men Sitting near a Coppice, in which the artist applies crisp thick lines to delineate hills and he composes architectural elements with sharp precision (Fig. 11). In contrast, Titian does not outline his landscape into a crisp image, but suggests hills and architectural elements with thin swift lines. For example, in his Landscape with St. Theodore Overcoming the Dragon of c. 1550, the artist applies fewer lines with a more rapid stroke, whereas Giulio provides more careful detail in his distant town (Fig. 13). Additionally, Titian’s foliage is applied with irregular marks suggestive of branches and leaves, whereas Giulio carefully outlines the leaves descriptively and with accuracy.

Campagnola’s drawing technique diverges from Giulio’s use of short and densely packed lines. Instead Campagnola apples long and wiry lines to activate the landscape with more movement and fluidity, a technique he likely observed in Titian’s work. His drawings combine the compositional structure and consistency of printmaking techniques he learned from Giulio with the atmospheric effects achieved by Titian. This can be observed in his landscape drawing Landscape with Musicians, where his composition is structured similarly to Giulio’s drawing, with a clear foreground, middleground, and background (Fig. 14). Domenico’s application of lines are parallel to each other similarly to Giulio; however, Domenico has freed his style from Giulio’s rigidity by liberating the line with the expressive and sinuous approach found in Titian’s landscape.

Though only eleven of the twenty-four Campagnola drawings that were used for the de Neyt set have been found, they can still reveal much about their making, use and re-use later as models for the etchings. It is possible that the drawings were part of a sketchbook or collection of drawings that entered Northern Europe as a resource for painters, such as Rubens, to have access to readily available landscape designs for their own compositions. Campagnola’s preliminary chalk technique indicates that the artist planned the drawings before committing to the design in ink, which might suggest that the drawings were intended to be finished works of art, sold to collectors for their virtuosity of technique. Though perhaps intended to be finished works, Campagnola’s technical achievements in the linear mode could more easily be reproduced by printmakers using the etching method for the de Neyt set. Campagnola’s drawings exhibit elements from both his mentor, Giulio, and the influence of Titian’s work. The drawings prioritize gesture, expression, and atmosphere, however when transferred to the etched set, these Titianesque qualities are not transferred, but are instead transformed with a new set of priorities for a new Northern audience.

[1] One drawing, from the Louvre is attributed to Titian, though scholars, including Ann Sievers and Bert Meijer attribute the drawing to Campagnola. Ten of the drawings can be found in previous scholarship, though one new drawing has been identified and corresponds to the fourteenth etching in the series, for a new total of eleven matching drawings. For the identifications, see, Ann Sievers, Master Drawings from the Smith College Museum of Art, (New York, Hudson Hills: 2001), 43n13. Bert Meijer identified six of the drawings, Maria Agnese Chiari identified one, Robert Cafritz identified two, and Ann Sievers identified one.

[2] See “Checklist” for drawing measurements.

[3] Erik Duverger, “Over dit hoofdstuk/artikel,” geschiedenis van de Vlaamsche kunst V (Antwerp, 1949), 20.

[4] Alexandra Onuf, The ‘Small Landscape’ Prints in Early Modern Netherlands (London: Routledge, Taylor and France, 2017), 12.

[5] Robert Cafritz, Lawrence Gowing, and David Rosand, Places of Delight: The Pastoral Landscape (Washington: Phillips Collection in association with the National Gallery of Art, 1989), 116.

[6] Cafritz, Places of Delight, 116.

[7] Sievers, Master Drawings, 40.

[8] Sievers, Master Drawings, 40.

[9] Cennino Cennini, The Craftsman’s Handbook, trans. Daniel V. Thompson, Jr. (New York: Dover Publications, 1960), 17.

[10] Cennini, The Craftsman’s Handbook, 17.

[11] Sievers, Master Drawings, 43.

[12] Beverly Louise Brown, “From Hell to Paradise: landscape and Figure in Early Sixteenth-Cntury Venice,” Renaissance Venice and the North: Crosscurrents in the Time of Bellini, Dürer, and Titian (New York: Rizzoli, 2000) 490. For more on Domenico Campagnola, see, G. Fiocco: “La giovanezza di Giulio Campagnola,” L’Arte, 18 (1915), 137–56, R. Colpi: “Domenico Campagnola, nuove notizie biografiche e artistiche,” Bollettino del Museo civico di Padova, 31–43 (1952–4), pp. 81–111, and The Genius of Venice, 1500–1600, ed. J. Martineau and C. Hope (London, RA, 1983–4), 248–53, 310–15, 320–21, 324–8.

[13] Brown, “From Hell to Paradise,” 490.

[14] Campagnola Family, in the Grove Art Online, http://www.oxfordartonline.com.silk.library.umass.edu/groveart/view/10.1093/gao/9781884446054.001.0001/oao-9781884446054-e-7000013477?result=2&rskey=OmFDUC (accessed April 23, 2018).

[15] Campagnola Family, in the Grove Art Online.

[16] The Louvre, “Landscape with Two Men Sitting near a Coppice,” The Louvre, https://www.louvre.fr/en/oeuvre-notices/landscape-two-men-sitting-near-coppice (accessed April 23, 2018). The web entry notes that the authorship of the drawing could be attributed to either Giulio or Giorgione, though ultimately ascribes the work to Giulio.

[17] The Louvre, “Landscape with Two Men Sitting near a Coppice.”