Walter Gibson observes that Dutch landscapes are almost always inhabited by anonymous working men and women, however, these peasant figures are often overlooked.[1] Though frequently disregarded, the peasant figure’s enhanced detail and sharpened clarity made throughout the etched set suggests that they were actually given increased attention and agency. The opposite appears to be true for the Campagnola drawing, where the artist has given precedence to the elements of landscape. Besides Campagnola’s main figures in the foreground of his images, the smaller figures scattered throughout the landscape drawings are less detailed, and are placed to provide scale for the trees and other scenic imagery. Gibson notes that the pseudo-French term, staffage, meaning “to decorate or garnish,” was used to describe these unimportant figures as a form of ornament in the Dutch landscape. It appears that the staffage in the de Neyt etchings actually did have a vital role in the function of the set, where there is more critical attention to particularizing these small figures.

The Venetian pastoral tradition has its origins in the importance of painting as a type of poetry, established by the Roman poet Horace that “Ut Pictura Poesis” (as poetry so is painting), an idea that the humanist, interested in classical texts, would have been familiar with. Other poems, rich in pastoral description, by poets such as Theocritus and Virgil would also contribute to the revival of pastoral poetry. The pastoral landscape genre occurs in paintings by Giorgione, such as The Tempest (1505-1510) and also in the work of one of Campagnola’s most admired influences, Titian, in his Pastoral Concert (1510).

(Fig. 3) Domenico Campagnola, Mountainous Landscape, with a woman crossing a footbridge in foreground L Christ Church Oxford, c. 1550s.

Campagnola experimented with landscape compositions as early as approximately 1516 and one of his earliest designs focused on the genre is Rocky Landscape with a Dense Wood. (Fig. 1). A major difference between this early landscape composition and his later dated works, used for the de Neyt set, is the thick and densely packed woods in the middle ground blocking our view into the distant landscape. Campagnola’s later landscape drawings dating to the 1550s appear become more expansive panoramic vista views. Without the impenetrable wall of trees, Campagnola could show atmosphere and distant views. Campagnola’s drawing composition evolve into what Catherine Whistler rightfully notes, “landscape prints and drawings enacted for viewers in a fresh an innovative way the paragone debate on the superiority of different forms of visual or literary representation. The challenge of representing in black in white, and in a linear medium, the variety of nature—including atmosphere and changing weather conditions as well as the illusion of distance—and the construction of an often enigmatic narrative, was closer, it could be argued, to the poet’s task than to the efforts of the painter of sculptor.”[2] The small scale of these works on paper would have prompted an intimate and close study of the image, similar to the way in which a reader engages with the poem.

(Fig. 4) Anonymous maker, Eleventh etching in the de Neyt set, 17th century. © Fondation Custodia, Collection Frits Lugt, Paris.

Campagnola takes on the challenge of representing a vast landscape with just the thin lines of his pen on paper. The smaller figures that appear throughout his designs are used less for a narrative or descriptive purpose, but instead to elevate the importance of the drawn landscape. For example, in the drawing Landscape with Figures and Animals, shepherds are drawn with little detail and are placed in the foreground to give a sense of scale for the tall trees and hillsides (Fig. 2). Moving farther into the distance to the right, Campagnola drew two figures, smaller with even less detail, to suggest a deep recession of space. The inclusion of these small figures throughout Campagnola’s drawings seem to dissuade the viewer from settling on their presence, but instead function more as a means to enrich the vastness of the landscape or help move the viewer’s eye throughout the landscape. The small, peasant figures contrast with the effortless beauty in the vast and profound landscape. The landscape envelops the scene, thus reducing the peasant labor and efforts as inconsequential within the bigger picture.

(Fig 5) Anonymous maker, seventh etching in the de Neyt set, 17th century. © Fondation Custodia, Collection Frits Lugt, Paris.

During Campagnola’s career, there was a rise in the depiction of peasant scenes within the Venetian pastoral landscape. Larry Silver points out that, “[s]ocial distinction and hierarchy lay at the foundations of all peasant depiction, marking most peasant representations in art as objects of social distance, even if peasants could sometimes be inverted from their usual notion of inferiority to be made into paragons, a rural kind of ‘noble savages.”[3] In regard to the drawings and prints in the de Neyt set, there is surely a social distinction being made that places the peasants in an inferior position. For example, in the Campagnola drawing (Fig. 3) and its corresponding eleventh etching in the de Neyt set (Fig. 4), the perspective of these designs rises slightly above the scene, elevating the viewer to a higher position than the peasant who carries a load on his back crossing a bridge. We view the scene from above, where we can even see the top of a broken tree trunk. This design, and the others from the set, allow for an expansive panoramic view of the landscape; the viewer is “playing” God.

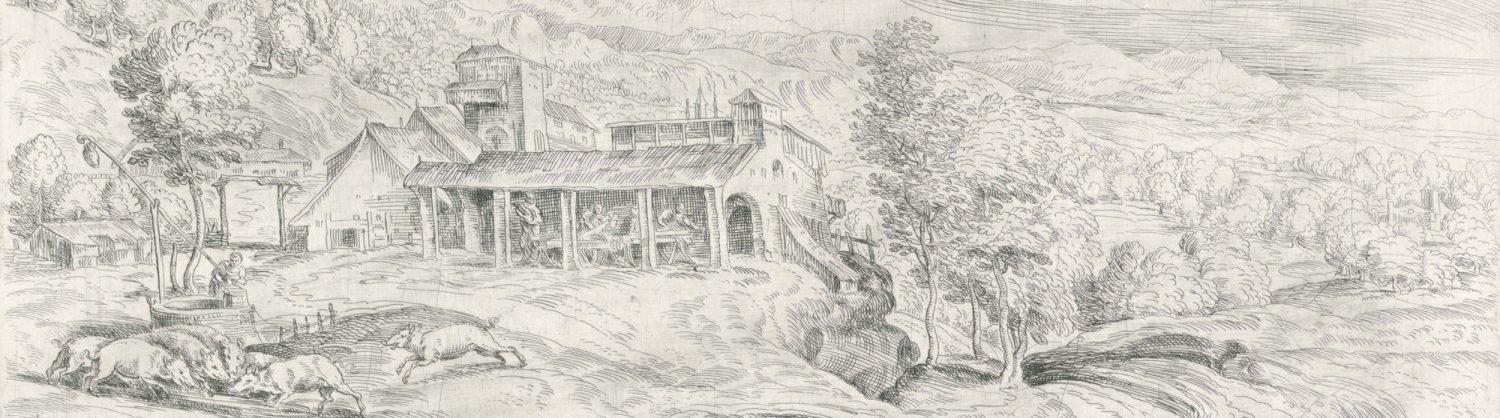

(Fig. 6) Domenico Campagnola, Landscape with Farm Buildings with Carpenters and a Herd of Swine at a Trough, c. 1500-64.

Though both the drawings and etchings make this social distinction, they differ in the amount of detail given to the small figures. Campagnola’s figures are inconsequential compared to his efforts to depict the landscape, whereas the etchings enhance the figures with more clarity and detail and give them a more crucial role. This could be a result of the new creative force between 1550 and 1630 in Antwerp where the de Neyt set was produced. During this period, three major innovations occurred: an increase in sets of prints with allegorical figures, Christian themes, and moral examples, an increase in sets with biblical illustrations, and an increase in sets of landscape prints that would dominate the market.[4] This increased interest in moral themes and landscapes might have impacted the new and more vital function of the peasant and figures within the de Neyt set.

(Fig. 7) Anonymous maker, nineteenth etching in de Neyt set, 17th c. © Fondation Custodia, Collection Frits Lugt, Paris.

A common theme among all of the etchings in the de Neyt set is the working peasant within an extensive panoramic rural vista. Almost all of the figures depicted in the set are performing a type of labor, but when compared to their matching drawn designs, the etched figures have been more carefully delineated and detailed with more distinct characteristics. For example, this growing importance on the figures within the landscape can be observed in the seventh etching (Fig. 5), and the matching drawing, Landscape with Farm Buildings with Carpenters and a Herd of Swine at a Trough (Fig. 6). In both, a peasant leans over a well to pull up a bucket of water. Campagnola’s drawing gives us just enough information to discern her figure. She does not any recognizable facial features, yet her small oval head on a hunched body can be detected. However, when the drawing was reused for the seventh etching, we are provided more detail of the woman’s face, characterized by a furrowed brow. The extra care to characterize this woman in the etching acknowledges her labor before the viewer’s eye can wander to another detail.

Likewise, in the nineteenth etching and corresponding drawing, Landscape with an Old Woman Holding a Spindle, a similar distinction can be made (Fig. 7 and 8). All of the small wandering figures placed throughout the landscape in Campagnola’s drawing are comprised of short strokes of lines. The figures that roam in the right distance are almost indistinguishable, so lightly drawn with broken lines, that their bodies dissolve into the grassy fields around them. Yet, in the etching, these same figures stand taller and carry a type of weapon or staph. Their more prominent placement in the scene advances their function in the landscape and their added objects give the viewer more to question about their role as they walk toward the city gates. Are the returning from a battle? Are they intruding this small town? Are they peaceful, or violent?

The presence of the figures throughout the set have an equal, if not more vital role within the landscape, where their presence holds the viewer’s attention, rather than turning it away back to the landscape. With the addition of the moralizing Latin quotations in the etched set, it seems as though Campagnola’s importance of the landscape falls short and the interest in the human presence within the landscape take on a greater importance. The inscriptions add narrative and moral contemplation, often relating to the figures and animals depicted, offering the viewer who study the etched prints a strong connection to the human presence.

[1] Walter Gibson, Pleasant Places The Rustic Landscape from Bruegel to Ruisdael (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2000), 117.

[2] Catherine Whistler, Venice and Drawing 1500-1800: Theory, Practice and Collecting (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2016), 160.

[3] Silver, Pleasant Scenes and Landscapes, 108.

[4] Griffiths, The Print Before Photography, 172-173.