First published at 3 Quarks Daily.

___

In the long and evolving list of cognitive biases, the ‘frequency illusion’ feels most familiar: I’ve experienced it so many times that it seems almost ordinary. This is roughly how it works. First, you encounter something – an unusual word like ‘topology’, or the title of a new book or a movie – that makes you stop and notice. Then, in the days after, the same word or title crops up again and again in unrelated places, making it seem more frequent than it is (hence the name). A friend brings it up unprompted, or you unexpectedly see it at a museum exhibit. It’s not only about words or titles, of course: anything in your conscious experience – a sound, an image, a fragrance – that makes an impression can be a point of entry. Buy a new car and in the weeks that follow, you will likely start noticing others driving the same model.

The most wonderful thing about this illusion is that with each seemingly unplanned encounter there’s a thrill of recognition, a feeling that the universe is signaling to you. The rationalists among us, however, will point to a more mundane explanation: that our cognitive processes have simply been primed to notice or identify the word, image, or sound among all sensory experiences. The illusion works in concert with two other biases: selective attention, the act of focusing on certain things while excluding others; and confirmation bias, the tendency to seek evidence that supports one’s beliefs while overlooking evidence to the contrary.

The recognition that these are only tricks of the mind can be somewhat deflating. But the processes that decide what we pay attention to and what we ignore remain mysterious. Something can be frequent in my everyday experience – say, a fire hydrant that I walk past each day – yet I may not notice it at all for years. Or I might be only vaguely aware of the hydrant’s presence, as if it lives in the background of my conscious experience. Then one day, I ‘stumble’ upon it, as if I am seeing it for the first time. Details such as its shape, color, and peeling paint register in a way they never had before. From that point on, I will naturally notice fire hydrants elsewhere. But I am seeing what was already commonplace; the frequency is not an illusion.

So the more intriguing question is: Why do things that we overlook all the time, things that are hiding in plain sight, suddenly catch our attention one fine day? And what is it about our cognitive processes that filters out certain stimuli and emphasizes others? Certainly, there’s an element of chance that puts you in the right place and at the right time to experience a stimulus. And each time you find yourself in the same place, the experience is subtly different, and you notice something new (in the same way that reading a book again seems to highlight things we’d missed). There also seems to be an inner realignment: an increased interest or receptivity to the stimulus that was previously absent.

The stimulus doesn’t have to be something sensory. Almost every semester, while teaching concepts that I’ve gone over plenty of times before, some nuance that had been hiding in plain sight will bubble to the surface, and I’ll wonder: Why didn’t I think of this before? And many years ago, while starting a meditation practice, I remember being startled by chaotic thought patterns that ran rampant in my mind. But the thought patterns also felt familiar – the difference was that I’d never given them proper attention before.

§

The terms ‘illusion’ and ‘bias’ suggest that we should look past the synchronicities that feel meaningful to us. That’s certainly true – there’s always a risk of reading too much into illusory patterns and of slipping into echo chambers; and online recommendation algorithms only worsen these tendencies.

But when used in the context of enhancing one’s observation skills, the frequency illusion can lead to a constructive form of learning. It makes you ‘zoom in’ on one thing, so to speak, and as you encounter it repeatedly, something else captures your attention, and you zoom in on that. This process of moving from one thing to the next continues, and soon you are discovering and learning in an endless sequence. Endless because there isn’t a limit to the new things you can notice, even in very familiar settings. And because this process of learning happens at a leisurely pace and is driven by what naturally captures our interest, it is deeper and more lasting.

In my case, the frequency illusion has led to a decade and a half of ‘recreational ecology’ (a slight twist on ‘recreational biology’, a term used by the Stanford bioengineering professor Manu Prakash).

It started in the spring of 2010 — my third year in Amherst, Massachusetts — when I saw a male cardinal for the first time. Cardinals are among the most common birds in North America, so it was a classic case of noticing something that was already frequent. I didn’t know anything about birds back then, and I was wonder-struck by the beauty of the male cardinal: its redness, the patches of black around its beak and crest. That spring, I ran into cardinals all the time, and each time I felt as if I had access to a special secret. Soon, I started to see (and hear) other all-season, backyard species that, like cardinals, were hidden in plain sight. First gold finches, then blue jays, then woodpeckers, nuthatches, house finches, and so on and so forth. It felt as if a portal into nature had opened up.

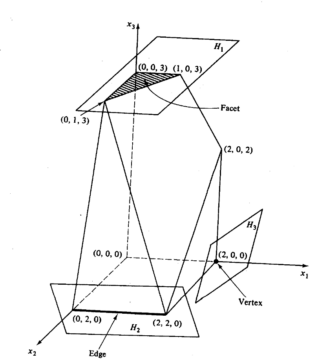

This kind of sequential and serendipitous discovery resembles a concept I teach in my probability courses: a biased random walk on a graph where in each step you probabilistically jump from one state (also called a node or vertex) to another. With a large number of steps, you can end up in less-explored states of the graph.

My ecological random walks have led me to lesser-known birds (my favorite this year is the Blackburnian Warbler), but also to so much else: bobcats, phantom craneflies, snapping turtles, rare seasonal flowers like Pink Lady’s Slipper, ferns, lichens. Each discovery illuminates a tiny piece of a vast and unfathomable ecological jigsaw. The process continues even when I am traveling. Soon after I had become familiar with the belted kingfisher in Amherst, I ran into the riotously colorful white-throated kingfisher near my parents’ flat in Bangalore, India.

The simple act of paying attention to visual, auditory, and olfactory cues can take you far, but learning can also happen in other ways. A few weeks after reading Elizabeth Tova-Bailey’s The Sound of a Wild Snail Eating, I saw my first gastropod: not quite a snail, but a slug, its antennae quivering the wet asphalt of a parking lot (it still remains my only gastropod sighting). Often, reading something about a species can deepen the impact of observing it in the wild. The monarch butterfly is striking enough visually, but to know that it undertakes a seemingly impossible 2,000-mile overwintering journey from New England to central Mexico adds a different kind of wonder. I was so inspired that one winter I traveled to the forests of Michoacan to see millions of congregating butterflies.

(This coming together of the senses and the intellect reminds me of something the physicist Richard Feynman said. When an artist friend chided Feynman that scientific reductionism minimized the aesthetic beauty of a flower, Feynman disagreed and claimed that the opposite was true. The visual beauty was available to him too, and the scientific backstory – why the flower evolved colors, the fact that insects can also see colors and may even have an aesthetic sense – could only enhance “the excitement, the mystery and the awe of a flower.”)

§

One of the pleasures of learning in this way is the element of surprise: you can’t predict what will intrigue you next. This year, for instance, I am drawn to the towering transmission lines that run through state parks, carrying electricity from natural gas, nuclear, and hydroelectric plants scattered around New England. The lines run through a 50-meter-wide corridor that was hacked through dozens of miles of forest. This has created a unique ecology: an elongated clearing in a landscape otherwise dense with trees. The clearings are preferred by smaller bushes such as the mountain laurel, whose pink-and-white flowers bloom in June, and by prairie warblers, whose high-pitched song (heard only for a few weeks) always makes me pause.

Imposing, symmetrical, and extending far into the horizon like an infinite relay, the transmission lines bring a different kind of beauty to the landscape. I often found myself marveling at them during my hikes this year. From the tops of mountain peaks, I’ve used my binoculars to track them as they run like arteries through forests, towns, and substations. And now I am also paying attention to the smaller, T-shaped wooden poles – the capillaries of the network – that run through every street, carrying a tangle of cables and contraptions, connecting each home to the grid.

In the past, I seem to have tuned out these essentials of our infrastructure, possibly because I’d prioritized nature and rejected human-made things – what is called the ‘appeal to nature’ or ‘naturalistic’ fallacy. Maybe the hold of that fallacy has loosened somewhat. Or, the engineer in me is (finally!) starting to emerge. Whatever the reason, it feels like a welcome shift. The transmission lines have also led me to notice cell towers with their antenna arrays, the solar farms that seem to be popping up everywhere, and the fenced water stations that draw from aquifers.

Who knows, some years from now, to my recreational ecology, I might also add a recreational study of infrastructure!