I was in Santiago, Chile recently for the IFORS conference. Two universities — the University of Chile and the Pontifical Catholic University of Chile — jointly hosted the event. There was the usual socializing, dining and fun that happens at conferences. I met colleagues and friends from Latin America, Asia and Europe, and was able to explore the city a bit.

Santiago, home to 7 million Chileans, sprawls along the foothills of the Andes. Majestic, snow-capped mountains loom in the eastern skyline. Smog from the traffic, unable to escape the wall of mountains perhaps, lay suspended in a haze over the high rises. I noticed graffiti everywhere, with no wall or building left blank — this gave the city a somewhat edgy look. Still, when compared to the other Latin American cities I’d visited — Lima, La Paz, Quito, Mexico City — Santiago seemed wealthier.

The conference included a day trip by bus to the towns of Valparaiso and Vina Del Mar along Chile’s rocky coast. The drive took us through small towns, wineries, farms, and hills with cacti, palms, and eucalyptus trees. Our tour guide, Rafael, spoke of Chile’s history during the journey: how the Spanish, after their success in toppling the mighty Incas in the north, arrived in Santiago in 1541, after an arduous crossing of the Atacama Desert. They came looking for gold, a recurring fantasy of Spanish conquests in the Americas. In the decades that followed, they faced fierce resistance from the indigenous Mapuche. Like other Andean countries such as Peru, Ecuador, and Bolivia, Chileans have a mixed Spanish-indigenous ancestry. However, according to Rafael, Chileans are more European and are therefore lighter-skinned. He had the precise numbers for himself: “I am 54% Spanish, 44% Mapuche, and 2-3% African.”

Rafael also spoke of the country’s modern history: the coup d’état against Salvador Allende’s government; the adoption of neoliberal policies by Augusto Pinochet‘s regime; the massive protests of 2019-20 and ongoing turbulence in the country’s politics related to the re-writing of its constitution. In a memorable phrase, Rafael called Chile a ‘bipolar country’, swinging between the extremes of the left and right. Born in 1977, Rafael grew up during Pinochet’s military dictatorship. His father, a construction worker, was once detained by authorities. But his father’s hands were so battered from bricklaying and cement work that the authorities released him. Because of that incident and the detention and disappearance of thousands of other Chileans, Rafael grew up disliking Pinochet. But now he has a more ambiguous view. He feels that had Pinochet not intervened, the situation in Chile might well have been worse.

§

After the conference, I climbed up the San Cristobal hill and visited the Chilean Pre-Columbian Art Museum. I found some thought-provoking exhibits at the museum. Such as this 7th century pot from Peru’s southern desert region with a painting of three hummingbirds feeding on a flower. Because I’d seen a hummingbird the previous day in Santiago, hovering around and dipping its bill into an orange-petaled flower, I felt an instant connection to the unknown artist (or artists) who had painted a similar scene 1500 years ago. (Though I doubt that three hummingbirds can amicably feed together as depicted!)

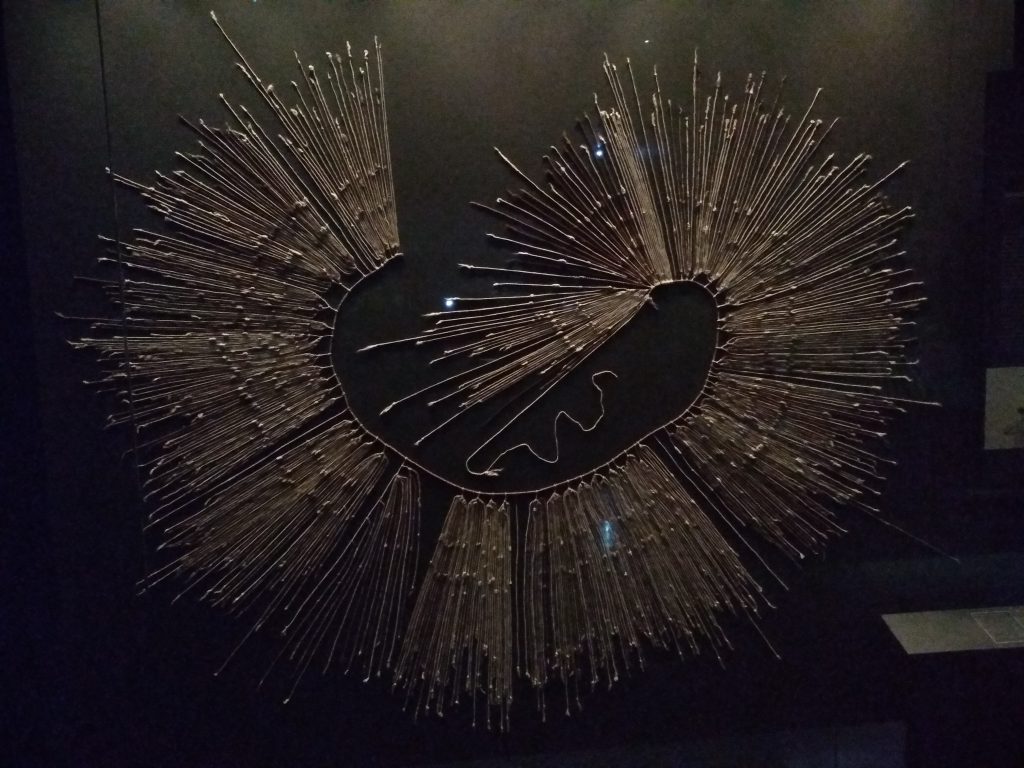

And this beautiful, abstract-looking exhibit below is a quipu . The Incas, who commanded a vast Andean empire, used quipus for administrative purposes. Each quipu consists of a primary “inner” cord to which all the radiating secondary strings are attached; each secondary string has a cluster of knots. Variations of this basic arrangement were used to record and convey quantitative data using a base-ten numeric system. Exactly what the logic is, I don’t quite understand; I guess you could think of the quipu as the string or textile version of an abacus. But — as I learned from the appendix of Charles Mann’s 1491: New Revelations of the Americas Before Columbus — some scholars have hypothesized that quipus were not just for storing numbers, they may also have been an unusual kind of writing system that is yet to be deciphered.