During the past week, we’ve talked a lot about video games and one reading particular got me thinking. “Do You Identify as a Gamer?: Gender, Race, Sexuality, and Gamer Identity,” by Adrienne Shaw, talked a lot about the gamer identity and how people perceived themselves in that sense. Shaw interviewed a diverse group of people, asking them if they considered themselves “gamers” and then asking their reasoning for their answer. During this, Shaw made an interesting find. On page 34 of the article Shaw notes “Although race, sexuality, age, and platform shaped people’s relationship with gaming,

these did not determine whether they identified as gamers.”

That quote prompted me to add a critical question to the discussion: “What do you feel are the qualities/traits that make someone a gamer?” This brought up many different answers but the more I thought about my own question, the more I came to realize that it isn’t an answerable question (at least not in my opinion). Being a “gamer” shouldn’t have some standard definition. Once we start doing that, we start excluding people, and even if the group is very small, that’s still exclusive. Think of it this way, if we go off Shaw’s article and determine that the traits noted above don’t play a part in determining if someone’s a “gamer”, then the next thing we hop down to is type of games being played.

If we set more competitive and triple AAA titles to be the standard games of a “gamer”, then suddenly we alienate those who play “casual” or mobile games. People who play games on their phone (which it’s worth noting that those games are becoming more and more complex so that stigma against mobile should just disappear as it’s pointless) and those who play browser based games aren’t allowed to call themselves “gamers” if we set those standards. And we shouldn’t be allowed to tell someone “No, you aren’t a gamer.” if they feel they are one.

If we abandon game type, and instead go to time playing games, we run the risk of achieving the same alienation. If we set a certain number of hours a week as the standard of being a “gamer” , than anyone who falls under it can’t be considered a “gamer” in the eyes of the gaming community. If someone plays Halo 25 hours a week, and I play Skyrim 5 hours a week, I’m considered less of a “gamer” or not even one by time standards. And again, it’s ridiculous to deny someone the title “gamer” for that reason.

The main point is, if someone seriously feels they are a “gamer”, who are we to deny them that. If the person who plays candy crush a few hours a week feels they are a “gamer”, then good for them! I welcome that. Anyone who wants to deny them that feeling of being a “gamer” is potentially aiding in creating a toxic environment. I think that the standard should be that anyone can be a “gamer” if they want to, and it’s up to them whether or not to say “No, I am not a gamer.” For me, it sort of falls on the line of a type of self-identity. It’s something you consider yourself to be, so why does someone else get to tell you that you’re wrong about that. Which is why it’s good that in Shaw’s article we see that people are starting to less and less feel that their race, gender, sexuality, etc. are something that determines if they are a “gamer.” If they felt differently, that indicates that the gaming community is setting strong standards for being a “gamer” based on those traits. The fact that they don’t feel that way shows that those standards of being a “gamer” are starting to fall off which is terrific.

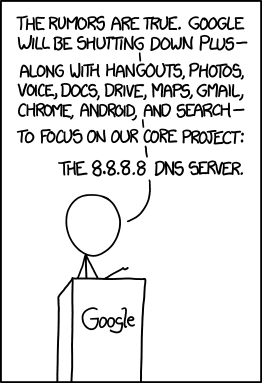

New media can counter monopolies and bring down corporations. But as we’ve seen, new media is a fertile ground for new companies and corporations, both of which could be just as bad, or worse, than their predecessors. Google is scary. At all times. It’s a bit like the supervolcano under Yellowstone National Park. We know that someday it will blow and change the world as we know it. We just don’t know when. It could be today. It could be tomorrow.

New media can counter monopolies and bring down corporations. But as we’ve seen, new media is a fertile ground for new companies and corporations, both of which could be just as bad, or worse, than their predecessors. Google is scary. At all times. It’s a bit like the supervolcano under Yellowstone National Park. We know that someday it will blow and change the world as we know it. We just don’t know when. It could be today. It could be tomorrow.