Once the parser delivers all possibilities to the calling function, it’s time to decide what’s what. What is a verb, what is noun, and so on. Because language is not mathematics, there is rarely a single answer. Instead, there are better and worse answers. In short, all possible answers need to be ranked. The best answer(s) are called “optimal.”

Once the parser delivers all possibilities to the calling function, it’s time to decide what’s what. What is a verb, what is noun, and so on. Because language is not mathematics, there is rarely a single answer. Instead, there are better and worse answers. In short, all possible answers need to be ranked. The best answer(s) are called “optimal.”

As far as I know, current iterations of the parsed corpora of OE treat all OE utterances as equivalent. In other words, the syntax of a sentence from the poem Beowulf is as grammatical as a sentence from Aelfric’s sermons. Bruce Mitchell, the greatest of OE syntacticians, compiled his conclusions from an undifferentiated variety of sources: “I have tried to select a variety of relevant examples or to illustrate the phenomenon from Aelfric and Beowulf, as best suited my purpose” (OE Syntax, p. lxiii). Although he noticed distinctions in syntax between authors, he attempted to derive from them a single form. For example, swelc ‘such’ is a strong, demonstrative pronoun in most OE writing; but it is used in a weak form “in ‘Alfredian’ prose” (sec. 504). Mitchell chased an abstract description of syntactic phenomena, whose instantiated form in language he illustrated with examples. Variants were classed as deviations from a norm. His was a Platonic quest. Mine, much impoverished by comparison, shall be a touch more Aristotelian.

Syntax will be subdivided generically. What is optimal in a prose chronicle may not be optimal in a poem.

Syntax will be subdivided temporally. What was optimal in Alfred’s court may not have been optimal in Cnut’s.

And syntax will be subdivided spatially, or rather, geographically. What was optimal in Anglian may not have been optimal in Kentish.

These subdivissions will have to be rough-and-ready, since we lack diplomatic editions of manuscripts. Editors have already elided much of the information that distinguishes one scribe’s work from another’s. For example, I noted in a manuscript of Aelfric an instance of OE faðer ‘father’, which was not supposed to exist at the time. As diplomatic editions come available, I will be able to account for them. For the moment, any dated or datable text will be marked as such. The “syntaxer” (program that parses syntax) will prefer texts of similar genre, locale, and time.

INDICES. The major component to the project is a set of massive indices.

Like a Google search, this parser operates on tables of frequencies. Google digests the raw web daily, at least. The web is then sifted through algorithms at Google’s massive data centers. That sifting process results in massive indices of frequencies. An index will record searches, links, and clicks. A search for Silly Putty is recorded. A second search. Then a third. Three users click on a single link. That link is recorded and marked as the top link. The next user to search for Silly Putty is sent the top link first.

An Aelfric index. By parsing the works of Aelfric, the computer can build a list of most-used words and their usual grammatical function in Aelfric’s sentences. So, someone searching for heald in Aelfric will prompt the retun of pre-parsed sentences, rather than invoking a new search. The sentences will come in order: the most usual use of heald first, the least usual last. (It seems most often to be in participial form.)

Other indices are obvious. A Wulfstan index. The works of King Alfred’s court. Benedictine books. The Chronicle. Poetry. And so forth.

PROGRESS:

Meanwhile, the parser is taking a sentence and parsing it!

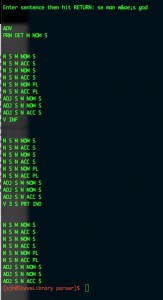

The first test sentence was, of course, “Hello, World!” Here is the screen grab of the first Old English sentence to work:

Se man wæs god. The correct forms are listed in each cluster.